-

-

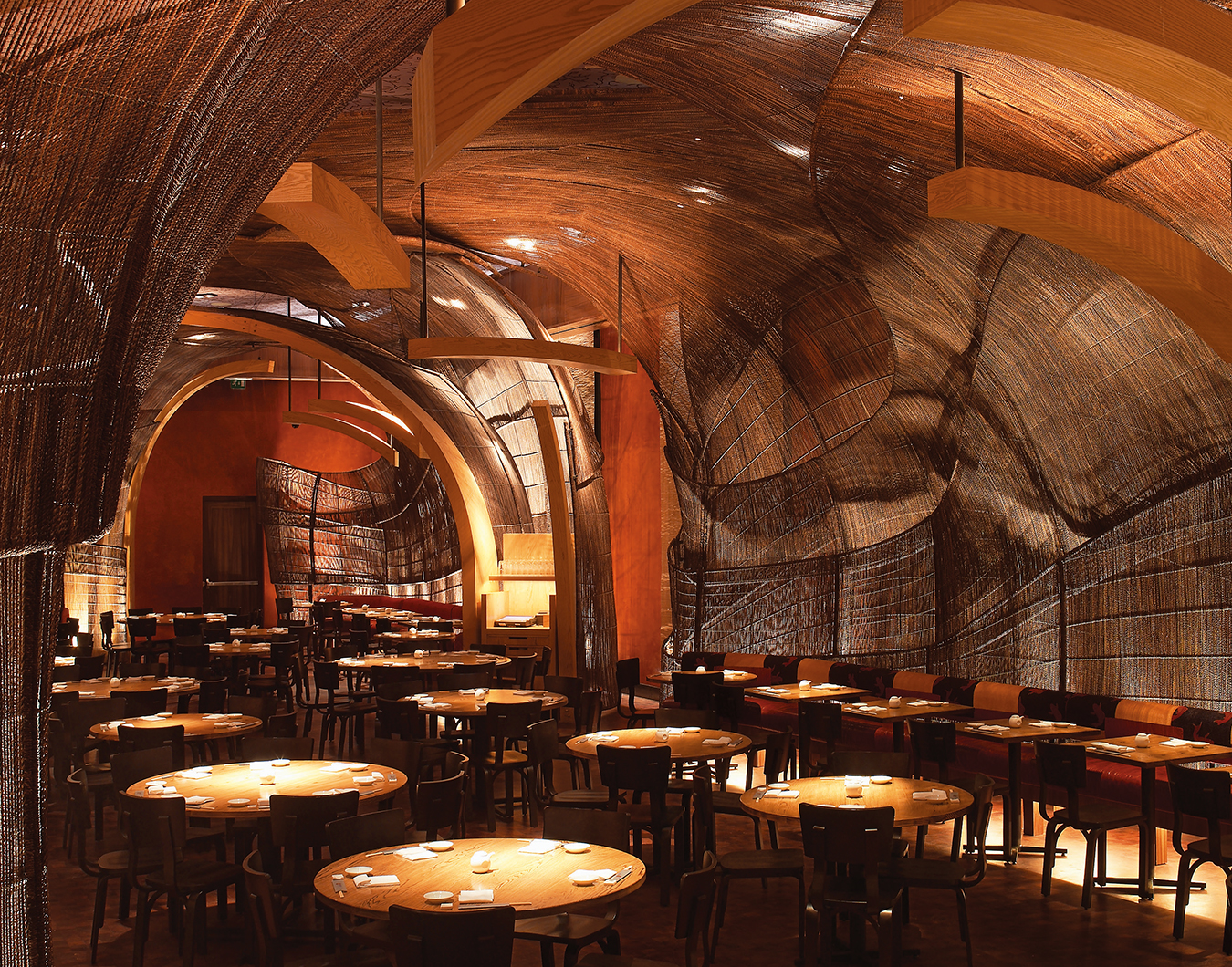

Ames Hotel in Boston. Photo ©Morgans Hotel Group.

-

-

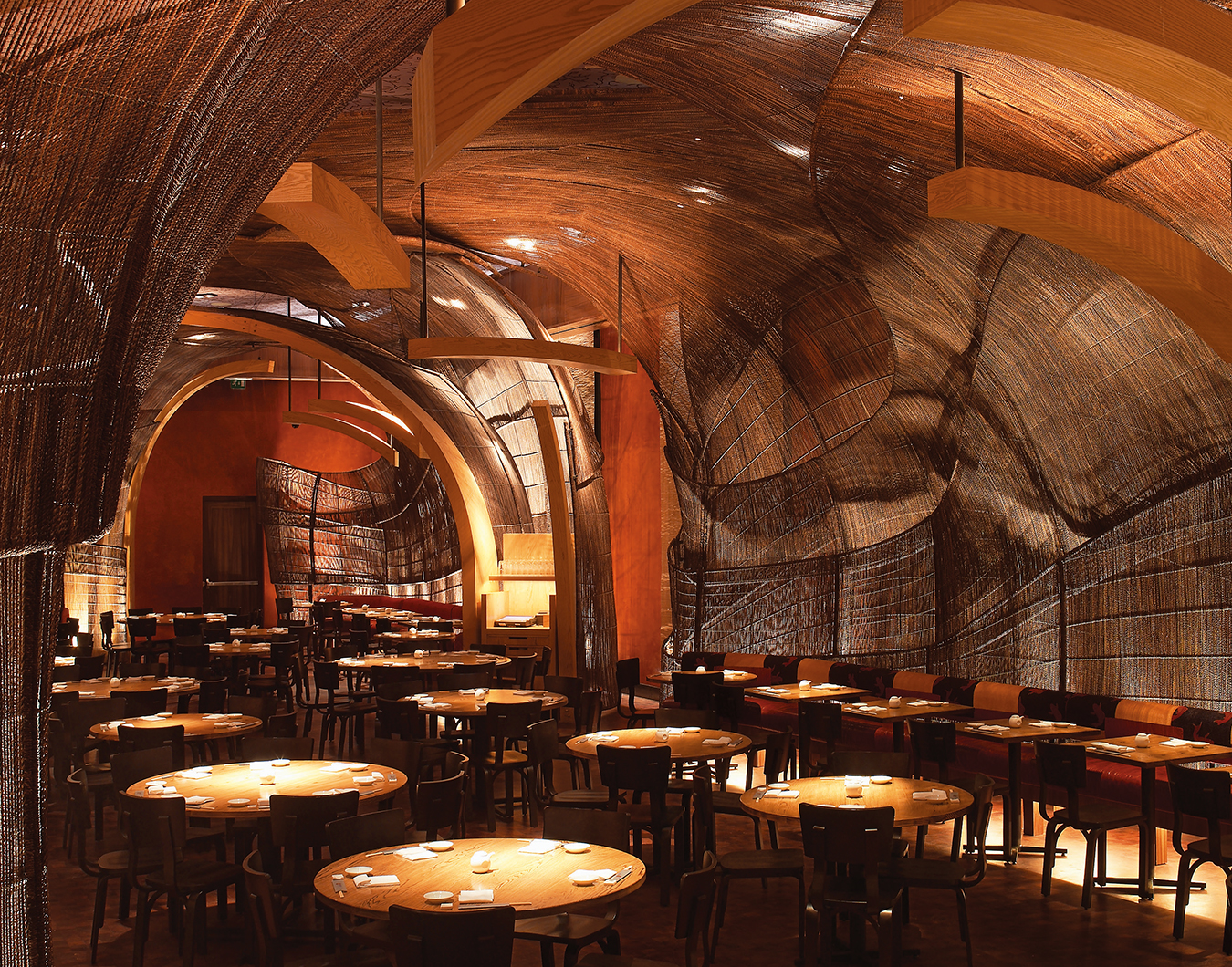

The dining room at Nobu restaurant in Dubai. Photo by Eric Laignel.

David Rockwell

Engaging environments.

David Rockwell is running 20 minutes late.

Seated at a table in his private office at his Union Square workplace, I surmise his surroundings, hoping for a sneak peek into the life of the man who has left his fingerprints all over the globe.

Bulletin boards display articles, drawings, and cards. Cookbooks and theatre tomes mingle with those on architecture and design. A clock in the shape of a TV, which bears the colourful logo for the musical Hairspray, sits next to antique mechanical toys. Another shelf houses a collection of kaleidoscopes placed next to an original drawing from Zorba and a set model from Stephen Sondheim’s Company. And let’s not forget the shelf of awards; a mere spattering of accolades he’s accumulated over his quarter of a century in the business.

Ames Hotel in Boston. Photo ©Morgans Hotel Group.

Finally appearing in the doorway, he slides, mid-apology, into a padded lime-green chair. “I’m sorry,” he says, his mouth busy with gum. “There’s a lot of running around today and I’m leaving for L.A. later.”

At 6 foot 1, the Chicago-born, New Jersey-turned-Mexico transplant has a looming, sizable presence. Clad in all black—T-shirt, slacks, shoes—Rockwell is a broad man with dark, thick wavy hair and a long, full face. He is one of the most important and sought-after designers of his time, a result of his minimalistic interior approach; his obsession with creating playful, interactive designs; his interest in the properties of light; and his passion for connecting and bringing people together.

His 140-person firm—composed of designers, craftspeople, model makers, artists, and sculptors—focuses on an array of projects, mostly hotels, hospitals, restaurants, and Broadway sets. Hotels include the Chambers, the Greenwich Hotel, W New York and W Union Square, and the recently opened Ames, a Morgans Hotel Group property in Boston. Of the more than 200 restaurants he’s designed, some of the most popular include Bar Americain, Gordon Ramsay’s Maze, and Nobu restaurants around the world. His love of anything theatrical led him to design the Kodak Theatre, the 81st Academy Awards show in 2009, and sets for Broadway musicals like The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Hairspray, and Legally Blonde. And let’s not forget the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Canyon Ranch Miami Beach, San Francisco’s Walt Disney Family Museum, and the JetBlue terminal at John F. Kennedy International Airport. Presently, he’s juggling 20 or so projects including the Elinor Bunin-Munroe Film Center at Lincoln Center and an Italian eatery for restaurateur Danny Meyer called Maialino at the Gramercy Park Hotel. He’s even working on two restaurant projects in Toronto’s Maple Leaf Square, as well as a major multi-use complex across the street from the Air Canada Centre.

No wonder he’s late.

“I love the idea that you don’t know what the next moment is going to be, or what can happen when a lot of transitions are forced upon you,” he says. Running a hand through his hair, he leans back in the chair and takes a breath.

Rockwell is no stranger to unexpected alterations. Growing up, he experienced a number of devastating and life-altering losses. “I come from a background where there were a lot of sudden transitions I couldn’t control,” he admits. “I’m the youngest of five boys, and my father died when I was three. My mother, who was a dancer in vaudeville, remarried, and at four-and-a-half we moved from Chicago to the Jersey shore. The large family I’d been part of sort of severed.”

Once settled in New Jersey, his mother helped found a community theatre group, which Rockwell says was right out of Waiting for Guffman. “It was the most communal thing that happened in our lives. I became fascinated with storytelling and making things: a spook house in the garage, an elaborate Rube Goldberg house for my dog, or carnivals for muscular dystrophy. So I expressed myself by putting things together.”

“My favourite project is the one I haven’t done yet,” says Rockwell. “I don’t want to get trapped into repeating myself. You’ve got to be willing to constantly take creative risks.”

When Rockwell was 11, his life changed drastically again, this time with a simple trip to New York. “I went to see Fiddler on the Roof at the Imperial Theater and before the show, we had lunch at Schrafft’s,” he recalls. “I’d never been in a New York restaurant before. When you have older brothers, dining out is an art. I remember … the sounds and sense of liveliness, and how everything was happing. It made me think of New York from the inside out.” Rockwell taps the top of his pen on the table while putting a fresh stick of gum in his mouth, and I realize he’s never still. “The show was fantastic. There was movement and storytelling. The image of the village of Anatevka said everything about it. The Chagall-inspired pieces showed the world was upside down.”

The following year brought a move to Mexico, which added more change and transitions to his life, as well as bursts of colour, light, a new language, and the understanding of public spaces. More loss came when he was 15 and his mother died from hepatitis, and still more when his eldest brother—the one he was closest to—died from AIDS. “At each loss I was devastated,” he says. “So I create, and hold onto to my family and mourn the people I lost.”

Rockwell does more than that. A self-proclaimed eternal optimist, he was intent on building little replicas of family. It is this need to recreate and reconnect with others that Rockwell keeps searching for. The desire to stay curious and driven, to find ways that design can bring people together and create a sense of community, fuels his quest for knowledge and passion.

No surprise, then, that he has also been working on the plans for the World Trade Center site. “As someone whose neighborhood was totally devastated by the September 11 attacks, I felt a real urgency to do something,” he says. “Ric Scofidio, Liz Diller, Kevin Kennon, and I all got together to brainstorm some solution for how we could help create a better experience for families and viewers as they mourn at the site of the World Trade Center. So we created a very simple, humble set of viewing platforms made of scaffolding and plywood where people could reflect and remember. It was a temporary creation, not a permanent memorial of any kind—four movable platforms that could respond to the changing conditions of the site and promote a dialogue and dignified place of mourning.”

Every space for him—public or social, theatrical or environmental—is about telling a story and revealing that place’s secretive narrative. His job: find it, capture it, and make it come alive while encouraging people to become emotionally and physically involved with the location.

“I never know where a space is going to lead me. You discover an enormous amount as you go along,” he says. “When I did the Oscars, I didn’t know the ending and that was terrifying. Doing new work requires a little bit of terror, as does putting yourself in a situation where you don’t know what the outcome will be. It’s live TV, and I was jumping into something that needed reinvention. It was a phenomenal experience. It was all about a great moment for me. I think if you worry too much as a designer, if you are too focused, you lose track of the ability to create the design that celebrates the moment.”

Rockwell offers to take me on a tour of the office, and seems relieved to have a chance to get up and move around. Aside from turning 53 this past July, his firm celebrated their 25th anniversary. Rockwell’s 2.5-floor, 30,000 square-foot space boasts three studios, a library where materials and fabrics are created and stored, a model shop, a technology lab, and a theatre area. As he walks down the hall he says hello to a co-worker, then welcomes a women back from vacation and asks how her trip was. His manner is easy; his warmth and comfort level with his staff, apparent.

“I’m motivated and compelled to work with smart, challenging people; great doctors, chefs and directors,” he tells me as we walk through a line of people working in cubicles. “And in each case I’m learning something. And whatever I’m learning, this great group takes it and applies it to design.”

As we take a slow lap, we pass by a light fixture made from bleached silkworm pods for Nobu, two hanging Kenneth Cobonpue basket chairs, and a mock version of a three-storey inhabitable chandelier. The life-sized, one-ton, $5-million (U.S.) creation was made to purposely fall on unsuspecting audiences during performances of Phantom—The Las Vegas Spectacular at the Venetian Resort Hotel Casino in Las Vegas. Like all of his work, the viewer becomes part of the production.

“Right now I’m very interested in portability and the idea of moveable structure,” he says, showing me a prototype of a transportable, stage-like configuration. “There’s too much infrastructure and not enough content.”

Every space for him—public or social, theatrical or environmental—is about telling a story and revealing that place’s secretive narrative.

Rockwell can invest years in a project. The JetBlue Terminal, which was designed with a public grandstand seating arena and restaurant, took five years to come to fruition. The unstructured, child-directed Imagination Playground at Manhattan’s Burling Slip took about the same. And Nobu, created thanks to research done on kabuki theatre, has been an experience that has lasted 15 years

“I’ve always loved what happens when dissimilar things rub together, when inspiration is found in the most unexpected places,” he says. “I’m also always looking for the familiar and surprising. The goal for a group like Nobu was to present Japanese food differently than a traditional sushi restaurant. One of the surprises we played with was introducing informality to the first three-star restaurant. We decided to do away with tablecloths. We made the chef the star of the show.”

Through countless investigations, man on the street interviews, storyboards, renderings, fabric swatches, floor plans, and photos, Rockwell creates a personal narrative.

“I interview clients and try to bring out the script. I want specifics when I’m doing the work,” he adds. “There are a million requirements—schedules, budgets, availability—and they all rip away at the concept. You have to have a concept that is strong enough to punch through all of that. I’d like people to have a greater sense of the possibilities of creative space. I also want to make them part of the interaction.”

For Adour, Alain Ducasse’s wine bar and restaurant at New York’s St. Regis Hotel, Rockwell realized that the chef was going to have 3,000 bottles of wine to offer guests.

“We wanted to show what’s usually hidden. So we created a motion-activated menu. We made the sommelier interactive. We let guests become part of the decanting process.”

For the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, everything was designed with an age-specific focus. Dozens of kids were interviewed about what it was like to be a patient. Rooms were then created so each child could customize design their room with music and colours.

We circle back to his office. There’s lots of stimulation and an organized-disorganized feel. Like Rockwell, his workspace is comprised of many layers that reflect his passions and projects. On his desk sit stacks of magazines, article clippings, books, papers, Post-its and a Diet Coke. There are photos of his family, an oversized pencil, a self-assembled Timberkit toy. Rockwell is most excited by a sheet of Harry Houdini stamps, which make him smile like a kid on Christmas morning as he tells me about the Broadway musical he is producing, which will star Hugh Jackman as the notorious magician. This will mark Rockwell’s first leap into producing.

“My favourite project is the one I haven’t done yet,” he says. “I don’t want to get trapped into repeating myself. You’ve got to be willing to constantly take creative risks.”

When he isn’t sketching, collaborating, brainstorming, conceptualizing, problem-solving, mediating, meeting with clients, and accepting new projects, he can be found at the theatre or spending time with his wife and two children.

“I feel like I really had to grow up at an early age,” he admits, finally sitting behind his desk. Rockwell fills the large space easily. Comfortably. “I had to be functional so I learned to incorporate a sense of play. I’m one of these few people able to incorporate what they love into what they do. Yes, there’s pressure and multiple projects, but I have to keep in mind how amazing it is to get to do the work I do and work with the people I work with.”

As much as Rockwell likes to be part of movement and action, this is the first time he’s appeared settled and complete. He is engaging, and gives off a powerful, Wizard of Oz–like impression. And just like the designs and architecture he creates, he makes me want to be a part of, and take part in, his environment.