Books of Brainy Soul

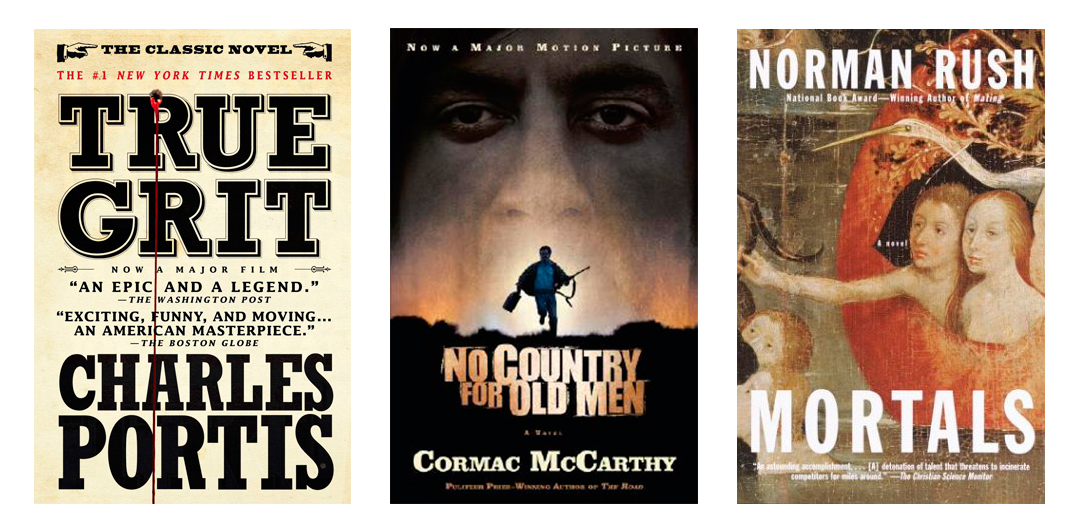

Books by Charles Portis, Cormac McCarthy, and Norman Rush.

Summer is over. Distant memory for you, perhaps, but for me, I’m being dragged out of it, my nails scraping furrows in August’s deep green shag carpet.

I love the summer because, at last, I can read whatever I want. The mounds of books heaped up hopelessly all over the house get rifled for filling the empty spaces in our luggage, and off it all goes to Nova Scotia, or the Kawarthas, or wherever it is people have unwisely invited us.

For some reason I don’t know, this was a summer of men. Books filled with guns, adventure, even horses. I started in June with True Grit by Charles Portis. At Brick, we’d uncovered a new edition of this 1968 novel that’s just come out in England, with a new introduction by Donna Tartt, who proclaims it her favourite novel. We decided to publish the foreword, and then all of us at the magazine dove into the advanced reading copy we got from Bloomsbury. That little paperback is now a ragged dog-eared mess, its pages so softened by repeat thumbings you could use them to mop up small spills.

True Grit—later made into the John Wayne movie—is the story of fifteen-year-old Mattie Ross seeking justice for the murder of her father. She leaves home to find a man of “true grit” who will bring her father’s killer in, and she comes upon bounty-hunter Rooster Cogburn, a man who likes to do things his own way. Wayne, who played the fifteen-year-old girl (okay, I’m joking) put his mark on Cogburn, and for those who have seen the movie—but not read the book—Portis’s Cogburn is an even more spectacular creation than the one from the movie. A hard-drinking gambler with no time for anything but the job and the pay-packet, Cogburn has done it all, seen it all, and most importantly, survived it all. That an encounter with a fifteen-year-old girl almost undoes him is one of this unsentimental novel’s great charms.

The other is Mattie Ross herself, who is one of the most memorable fictional female characters of the last fifty years. The act of empathy required to get into this mind is unfathomable to me; the novel, written in her voice, might as well have been written by a young girl in 1870, that’s how rigourously true it is.

It’s a novel of wonderful setpieces and startling turns. I now know six more people who adore it and wouldn’t get long odds betting you would too.

In somewhat similar territory—lawmen, outlaws, and remote locales—but much more modern, is Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men. Much has been said of this novel already, especially the opinion that this is McCarthy-lite for those who adored The Border Trilogy, but would have glazed over in front of his difficult early novels (like Blood Meridian and Suttree). There is something to this, but not if it’s being offered as criticism. Of course any author is entitled to break from whatever mold they’re in (is A Midsummer Night’s Dream a bad play because it’s not Hamlet?); all books must be judged by the intent of the author and his or her execution of that intent. And in terms of this criteria, No Country for Old Men is a fine piece of work because it’s clear that McCarthy set out to write a fast-paced (almost movie-paced) novel of explosive violence. Its plotlines are simple: Llewelyn Moss, out for antelope one afternoon, finds instead a bunch of bodies in a field, a truckload of heroin, and two million dollars in cash. A rather brutal character, Anton Chigurh, is also interested in that money, and when Moss takes the money and leaves the state, Chigurh makes Moss his business.

Chigurh is the kind of character that will help you decide who to recommend this book to: not the fainthearted. In love with violence, and highly practiced in it, Chigurh commits a number of fantastical murders in this novel, and has a high time doing it. He lives by the kind of inverted moral code that McCarthy-aficionados will recognize, as it’s a staple of his world and the characters that populate it. Chigurh doesn’t just kill because he has a hankering for it, he kills to establish and maintain balance in the moral universe he lives in. He’s a great character, but he’ll chill your soul.

The novel also concerns a sheriff approaching retirement, a man by the name of Bell who would like to survive the last months of his employment, but is duty-bound to find Chigurh before the maniac kills Llewelyn Moss and everyone associated with him. The novel gradually turns into an exploration of the journey of this good man (who, like all good people, has doubts about his moral balance-book), and it’s McCarthy’s gradual revelation of this man’s soul that saves No Country for Old Men from becoming ready-made Hollywood fare. Although I doubt that’ll stop ‘em.

Not coming to a multiplex anytime soon is the film adaptation of Mortals, Norman Rush’s second novel. Readers may recall the paroxysms of joy I reported after reading his first novel, Mating, and Rush’s second is a worthy successor. This is another weighty, digressive, frequently annoying novel that nonetheless reaffirms one’s faith in literature. The joy of a difficult book is in committing to the journey—no one sits down with Ulysses only for the pleasure of it—and Rush is an author who rewards the reader’s patience and engagement. Mortals is another novel about love and partnership, again set in Botswana, but told this time from the point of view of Ray Finch, a man who idolizes his wife as much as the unnamed narrator in Mating obsessed over Nelson Denoon. (To this reader’s delight, the narrator of that first novel is finally named in this one. I won’t ruin that small pleasure for you, though.) Finch is a Milton specialist teaching at a good college in Kanye, as well as a CIA agent, whose main job is to gather information on parties of interest and write reports. (He is known for his sparkling prose.) But when Finch suspects that his wife is cheating on him with a newcomer to town, he tries to get his boss to assign him to explore the background of the man. This begins a slow—I admit, sometimes painfully slow—unravelling of both Finch’s marriage and his mind. His nemesis is David Morel, a hugely charismatic black American doctor who has come to Africa with the incredible goal of de-Christianizing the country. Some of the long passages in which Morel declaims on the flaws of the early Christians, the misreadings of the Old Testament, and his view that Christ—the practising Jew—would have been appalled at his promotion, is some of the most exciting intellectual shenanigans you could ever hope to come across. Rush doesn’t come close to offending his readers though, because although he is completely at home in the polemical, that voice is always trumped by passion and profound intellectual curiosity. It’s a delight to be present for it.

Mortals is another weighty, digressive, frequently annoying novel that nonetheless reaffirms one’s faith in literature.

Mortals, like its predecessor, turns on a long desert journey in which almost everything goes wrong and death seems a likely outcome. But Rush again manages the near-impossible: he turns this novel into a feast of action and suspense without ever sacrificing the brainy soul of the book. I imagine some readers, picking up either of these novels on my say-so, might want to track me down and beat me with them (even being hit with the paperbacks would produce satisfactory welts) and I can’t blame them for the reaction. Ray Finch is a male version of Mating’s narrator: endlessly questioning, full in equal measures of doubt and arrogance, verbally overwraught, paranoid, and unstoppable. But what saves both of them, and raises both of these novels to high art, is the profound sense of love in them, the real empathy for all of humanity, and the project of divining what makes us who we are. These novels are also, you may not be surprised to learn, often devastatingly funny.

Finally, let me say a word about another master. I’ve had to ration my reading of the early Coetzee books because every time I read one, I feel like I’ve been eaten alive. Life & Times of Michael K did the expected violence to my soul, but I can’t regret it. Coetzee must be read. This book, which tells of the life of an impoverished black man living through a war he has nothing to do with, is a spare, dark masterpiece. Michael K is a gardener who decides that his sick mother would do better in the country and he sets about wheeling her in a handmade cart to somewhere else. But when his quest fails (and his mother dies) he becomes a man without ties, a homeless person in the most spiritual sense, and gradually he falls in the clutches of the war he’s been trying to stay out of. He becomes a prisoner, but even that minor identification is too much for him, and Michael goes on a hunger strike that at first startles and then strikes the reader down with awe and horror. I read it in pain, but I loved it. It made the summer perhaps darker for a couple of weeks than it needed to be, but that’s a fair price to live in peace and freedom. Although maybe it was a book to be read in spring, with the promise of summer coming.