-

Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts: Twelve Journeys into the Medieval World by Christopher de Hamel.

-

Essayism by Brian Dillon.

Just Our Type: Summer Reads

Essential summer reading.

Essayism by Brian Dillon

Some books willfully set out to bend our expectations of form or genre. This top-down kind of invention can provide endless varieties of pleasure: epistolary horror sci-fi memoir, poetic interview–historical drama, graphic novel–political treatise for the stage. Other works carry the imprint of having been transformed from within, perhaps even against their will or better judgement. In Brian Dillon’s Essayism, we’re up close and intimate with a severe, probing, analytical mind as it attempts to understand its own abiding love of the essay form. In fact, Dillon loves the form so intensely, he’s unsure of its stability or definability as form. Leaning on his most beloved predecessors—Montaigne, Barthes, Hardwick, Gass, Woolf, Sontag—Dillon’s glitteringly articulate prose enacts its sleight of hand on the history of the essay, disassembling, questioning, adoring while quietly conjuring a new benchmark for the essay form without us noticing he’s done so. This is a beautiful, elegant book. It is also heartbreaking—at times scorchingly painful. Essays, for many readers, are loved for reasons that go beyond pure pleasure. The essay’s dual state, of being both perfectly succinct and somehow never complete, affords it a durability through time, through a life. We keep them to hand the way a believer requires sacred texts; they don’t ever stop giving over their best mysteries, their unfolding, unfinished, intimate, and fragmented wisdom.

The dissolution of a marriage, ensuing isolation, periods of profound depression, even suicidality and its attendant self-harm and self-hatred all get stared down with a poise, and grace, and lucidity not easily found in literature, let alone in your own life. To have found a space in which meditation on art and writing can hold hands so fraternally with troubled personal memoir is one of Essayism’s great triumphs. What could have collapsed into self-involved pity or bloated pretension is returned to us as a gift. To see a mind this outwardly engaged face up to its own weakness and fragility, to travel through pain and not around it, can be company to any one of us when it is company we need most acutely. As Dillon explains, “These writings seemed to confirm not only that disaster was real, and general, and happened even at the smallest levels of language, but also that the catastrophe could be turned. Art was nothing but an acknowledgement of this moment when you realized the cracks had been there all along, bony fate attending in the shadows for years.”

I will keep Brian Dillon’s Essayism to hand, as much for what it’s taught me about living as for what it reveals about one of our culture’s most shyly majestic literary inventions.

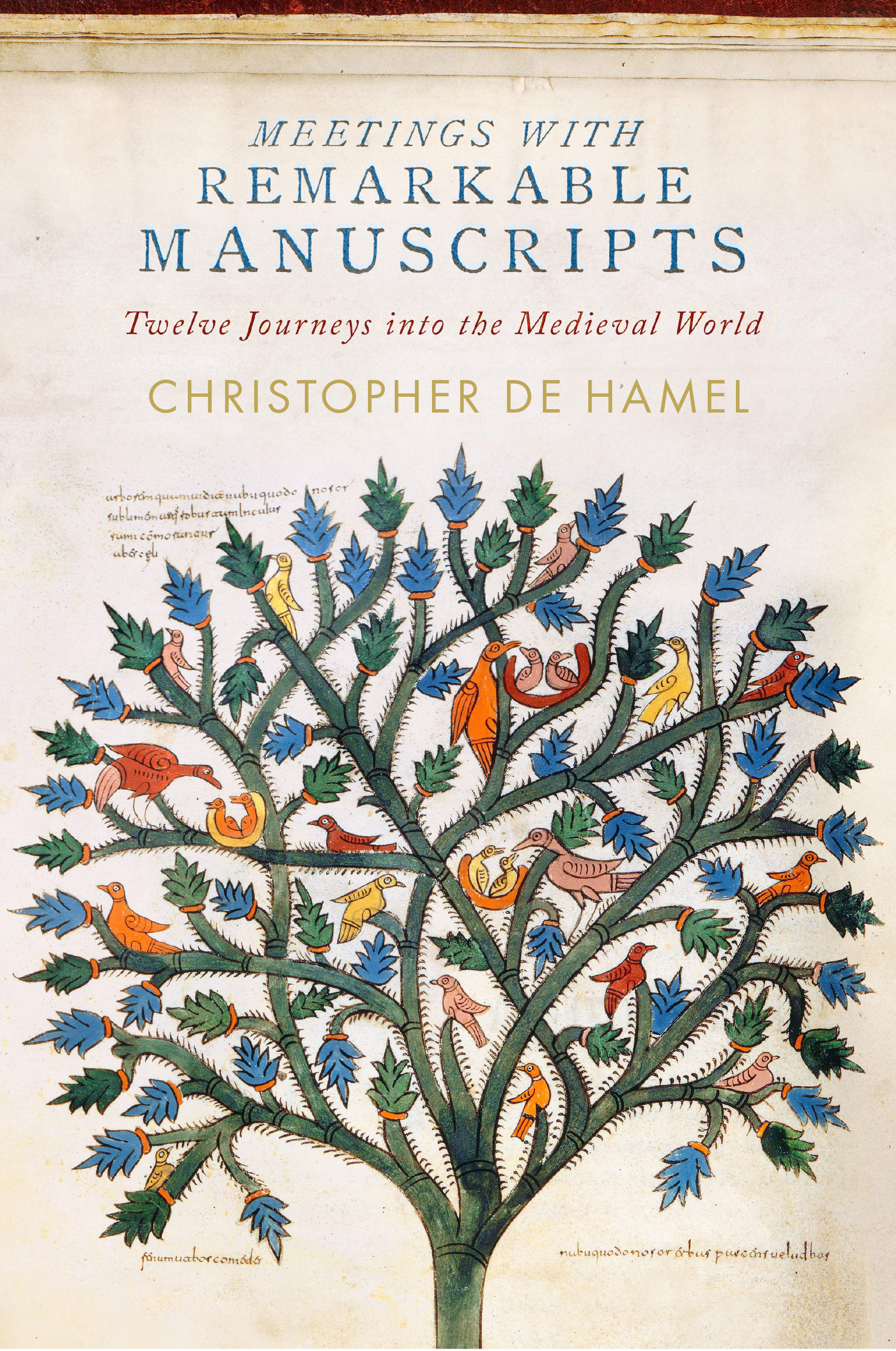

Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts: Twelve Journeys into the Medieval World by Christopher de Hamel

Christopher de Hamel’s Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts: Twelve Journeys into the Medieval World is a nearly uncategorizable compendium of knowledge and elegance, somewhere between an essay in 12 parts and a time-travelling reorganization of our perceived cultural past. De Hamel arrives at his subject as the consummate guide: a former custodian of the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, de Hamel had a lengthy tenure at Sotheby’s as the world’s foremost expert on illuminated manuscripts, cataloguing more of these medieval treasures than anyone anywhere. We’re invited into some of Europe’s great inner sanctums, the rare book-reading rooms of Paris, St. Petersburg, Florence, Cambridge, Copenhagen, and more.

And what are these manuscripts, exactly? What’s come down to us from the Middle Ages ranges from the instantly recognizable Book of Kells, a foundational text on which much of modern Irish cultural identity was built, and the bawdy drinking songs and love poems of the early 13th-century Carmina Burana, which fed Carl Orff’s musical imagination, through to the Visconti Semideus, a manual of war craft and strategy served up to a 15th-century duke of Milan (including how to launch poisonous snakes in bottles onto the decks of enemy ships). Looking at these exquisitely handmade artifacts of the past, we can only feel grateful, and even tender, toward a time when the textual dissemination of knowledge could be a slow burn thing: fine art in its highest and most hu-man expression.

Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, it must be said, has found its ideal publisher. Penguin Press has served up an outrageously beautiful object: 632 pages, more than 200 of which come adorned with exquisite colour plate reproductions of pages from the 12 medieval manuscripts, detailed blow-ups of strange marginalia, even photos of the rare bound objects themselves, which vary in size from the delicately portable Hours of Jeanne de Navarre to the unwieldy (and therefore very fragile) behemoth that is the Codex Amiatinus in Florence: “The spine—try to envisage it—is about 11½ inches across. The width tapers slightly towards the fore-edge. The manuscript is bound in very modern plain tan-coloured calfskin over wood with leather straps dangling from the lower board stitched with yellow thread and fitted with modern brass clasps which reach up to metal pins set in the edge of the upper cover. It looks, frankly, like a huge and expensive Italian leather suitcase.”

That final impression by de Hamel, that personal, warm, attentive voice, sitting in wonder in a cramped room within Biblioteca Laurenziana—the Laurentian Library—in Florence, flows through every chapter, somehow comfortably and winningly interwoven with a knowledge that so often excludes rather than invites readers into scholarly cultural corners. Is it insulting to trot out the cliché of having come away with the sense that I’ve spent time with the man as well as the manuscripts?

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.