Alain de Botton’s School of Life

The thinker.

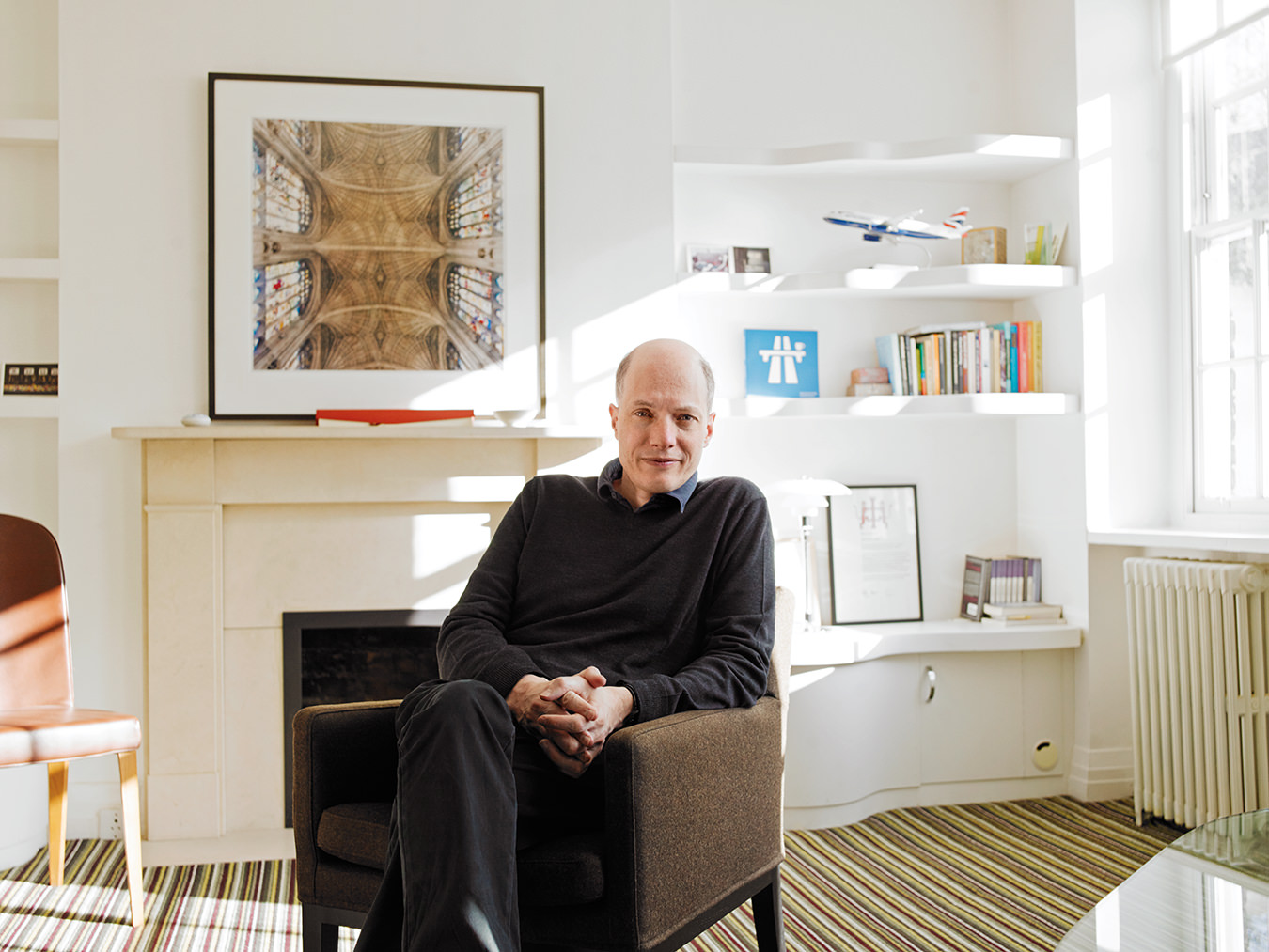

Alain de Botton lives in a house in North London distinguished from all of its neighbours by its newness. Modern housing in the British capital typically means new apartment buildings. Hundreds, if not thousands, of these far-from-handsome structures are going up all over town, and you can’t count the vast number of cranes you can see from the hills overlooking London. So, a freestanding modern house with its own garden in North London is very much an anomaly. Maison de Botton is a cube made of glass and sheet steel, while the rest of Belsize Park—which is south of Hampstead and north of Regent’s Park—contains large Victorian villas faced with red brick or white stucco, or a combination of both.

“New” is a central concept of de Botton’s. He’s written books about modern architecture. He runs Living Architecture, a social enterprise that builds and rents out modern houses around Britain with the idea of allowing people to see how they might live differently were they to immerse themselves in such structures. (He wants to build a new hotel in nearby Hampstead, but there have been objections from locals.) He’s interested in new ways to live, and it was with that in mind that he founded an institute in 2008, the School of Life, which concentrates on “emotional intelligence” and now has branches all over the world. The institute runs seminars and lectures on psychology, psychiatry, and philosophy. Cynical and pessimistic, he is not: life, for de Botton, is there to be improved upon.

Born in Zurich, de Botton began writing at a young age. He went on to study history at Cambridge University, complete a master’s degree in philosophy at King’s College in London, and publish the best-selling Essays in Love, his first novel, at the age of 23. Today, the 46-year-old has added much to his resumé. He’s written more novels, and of course, he’s written about philosophy. He’s a public figure, makes videos and uploads them to YouTube—the idea of self-production interests him—and is also involved with Seneca Productions, which he founded in 2003 to develop and produce series and one-off documentaries for major TV broadcasters in the U.K. and the U.S., such as the BBC, National Geographic, and the History Channel. So de Botton occupies a lot of ground: writing, teaching, lectures, books, journalism, novels, film, architecture. While he’s hardly the first person to recognize that utilizing many types of media is necessary if you are to successfully present ideas in this madly chaotic era—no one medium can act independently of another—he has spread himself widely so as to maximize the impact of his arguments. On the publication of his first novel over 20 years ago, one critic wrote: “This is not the last we shall hear of him.” This has been true, although that critic couldn’t have imagined de Botton would now be heard in so many different arenas.

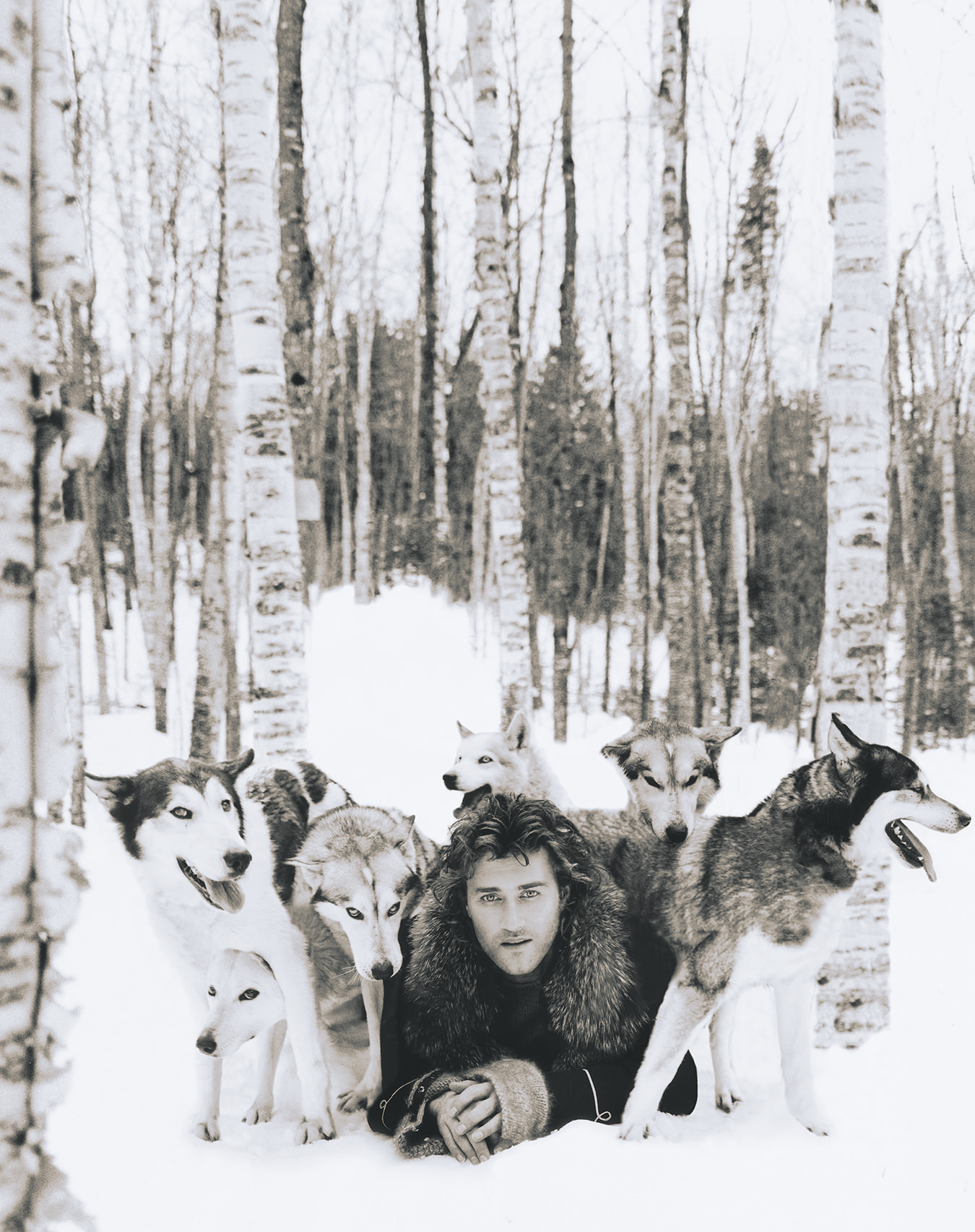

Modern he may be and new his watchword, but de Botton remains loyal to the book, and this interview takes place in his office, which is in an old apartment building next door to his new house. He sits in an armchair at a low glass table upon which there are two glasses and a bottle of San Pellegrino. He is bald, with an impish expression—from looks alone, his age is hard to determine. As an individual, rather than as a writer, de Botton isn’t easy to pin down. He doesn’t automatically offer up details of his life: if you are the prying type, he may brush aside questions about his private life. (He is married, to Charlotte de Botton, and they have two sons, Samuel and Saul.) That large new house of his is next door, and out in the open; it’s a conspicuous presence on a street of mostly 19th-century houses, only he doesn’t refer to it. You can’t help thinking that he has become somewhat inured to inquiries about himself.

Naturally that house is full of bookshelves, as is the office in which we sit, suggesting a library of someone who reads a lot. Still, de Botton notes: “The book world has changed. No one I know leads a book-focused life anymore.” This is his explanation for having a more hybrid existence. “The book used to be a more prestigious thing 20 years ago. But the glamour has gone.” That may be so, but his new book is a novel—a novel of ideas that, in his view, lies between an essay and fiction. The Course of Love is about a modern marriage, from its beginnings through its flourishing and then into an inevitable slog—years that unaccountably slip by as wife and husband go about careers and parenting. (It was published by Penguin Random House and released in the U.K. on April 28, with Penguin Random House Canada to release the book on June 14.) Kirsten McLelland is a chartered accountant, Rabih Khan an architect. At their first meeting: “They shake hands at the construction site on an overcast morning in early June, a little after eleven.” The rest is history, or the history of a marriage through courtship, togetherness, and a wedding, and into the lives of their children. Each phase of this married life is written in the present tense, and each chapter is interspersed with the reflections and commentary of what you might describe as the novel’s own in-house philosopher, who points out the subtext to the action—or inaction. That philosopher is moral—they have a view—but each of their many interventions is made with the idea of heightening the reader’s appreciation of the foundations, as well as the fallacies, of the ideas embedded within love and marriage.

De Botton believes people should give up the idea of finding perfection in their partner. “We are all broken and fallen, and we should learn to appreciate people for who they are.”

Romantic love is the problem, de Botton says, and he wants to find forms of love that don’t end in disappointment. “Why do we keep marrying,” he says—his questions and statements often sound much the same. “The Romantic story has been around for 250 years. The promise of a soulmate, the best friend, the co-parent chauffeur—our ambitions [in who we love] are very high,” de Botton says. He is articulate, speaks firmly and with concern, but there are no jokes on the de Botton horizon. Humour and laughter seem to have little place in his order. “There is this wish to prove you’re loyal to love. Yet there’s a recklessness and unreasonableness in that idea, because the demands of our lives are incommensurate with our ideas about love.” That is the parable of Kirsten and Rabih: they are two people who obviously love one another, yet the demands of the world make it hard for either of them to live up to the Romantic considerations that brought them together. Why?

Work and money are pivotal factors, only for de Botton they often get thrown out the window when it comes to love. “Jane Austen,” he says, “was very alive to the idea that money should play a role in love. There’s no violation to love if we think about it.” And yet, he thinks money divides marriages. So do children. “Children don’t have a role in the romantic narrative. Every couple in real life is sapped by the arrival of children.” He seems to take a bleak view of marriage itself: “I don’t think it is for everyone. There are very nice people who find themselves in situations they shouldn’t be in.” And then there’s the fearsome power of technology. “It accelerates our impatience with the tricky and boring aspects of living with people,” de Botton says. “It shortens our willpower to keep going because it allows you to find someone more interesting.” By presenting its users with so many fresh choices, technology can render people familiar and surroundings dull.

But it would be a mistake to think de Botton is against marriage. Far from it, but he does believe in the necessity of new thinking about matrimony, and that people should give up on the idea of finding perfection in their partner or spouse. “That leads to a lot of disappointment. We are all broken and fallen, and we should learn to appreciate people for who they are. Most people are mediocre: failure and a middle path is the norm.”

What’s the answer? De Botton has a keen interest in Dutch culture, and anyone who has been to the Netherlands can’t have failed to notice the prevailing urban feel of the place, more so than either the U.K. or the U.S., which are suburban by comparison. Central to Dutch marriage in previous centuries was the linen cupboard and tending to it. It’s de Botton’s contention that successful modern marriages need to construct their versions of the linen cupboard: an interest or a preoccupation that’s shared and intellectual, as well as possessing emotional attachment.

Given all of his endeavours and success, is his own way of life a recipe for marital success? De Botton doesn’t offer anything about himself; he prefers abstraction, but he speaks about the importance of staying focused on what you do. “Getting ideas across the line”—that’s how to describe his own abilities. “No one gets through this life without being bashed about,” he says of his success. No one would disagree; he’s made millions from his books, and success is always followed by those who’d like to knock you down a peg or two.

Soon, the sun will set behind the houses at the end of the west-facing garden, and de Botton will leave for his house next door. It seems he has the best of both worlds—a new, modern villa as well as a toehold in an old apartment building, and that while he is thinking of new ideas, he is nevertheless rooted in that old book world that he says is less a part of everyone’s lives than it once was. He has published a novel: how much more old-fashioned can you get?