Geoffrey Farmer

Canada's representative at the Venice Biennale.

“Oh, that’d be an amazing broom.”

Geoffrey Farmer, international art star and Canada’s representative at this year’s Venice Biennale (May 13 to November 26), has just found out my family ran a paint shop for three generations. The stockroom broom I’ve described, worn down to just a couple filthy inches of bristle, would go well in Farmer’s collection. He has a thing for brooms.

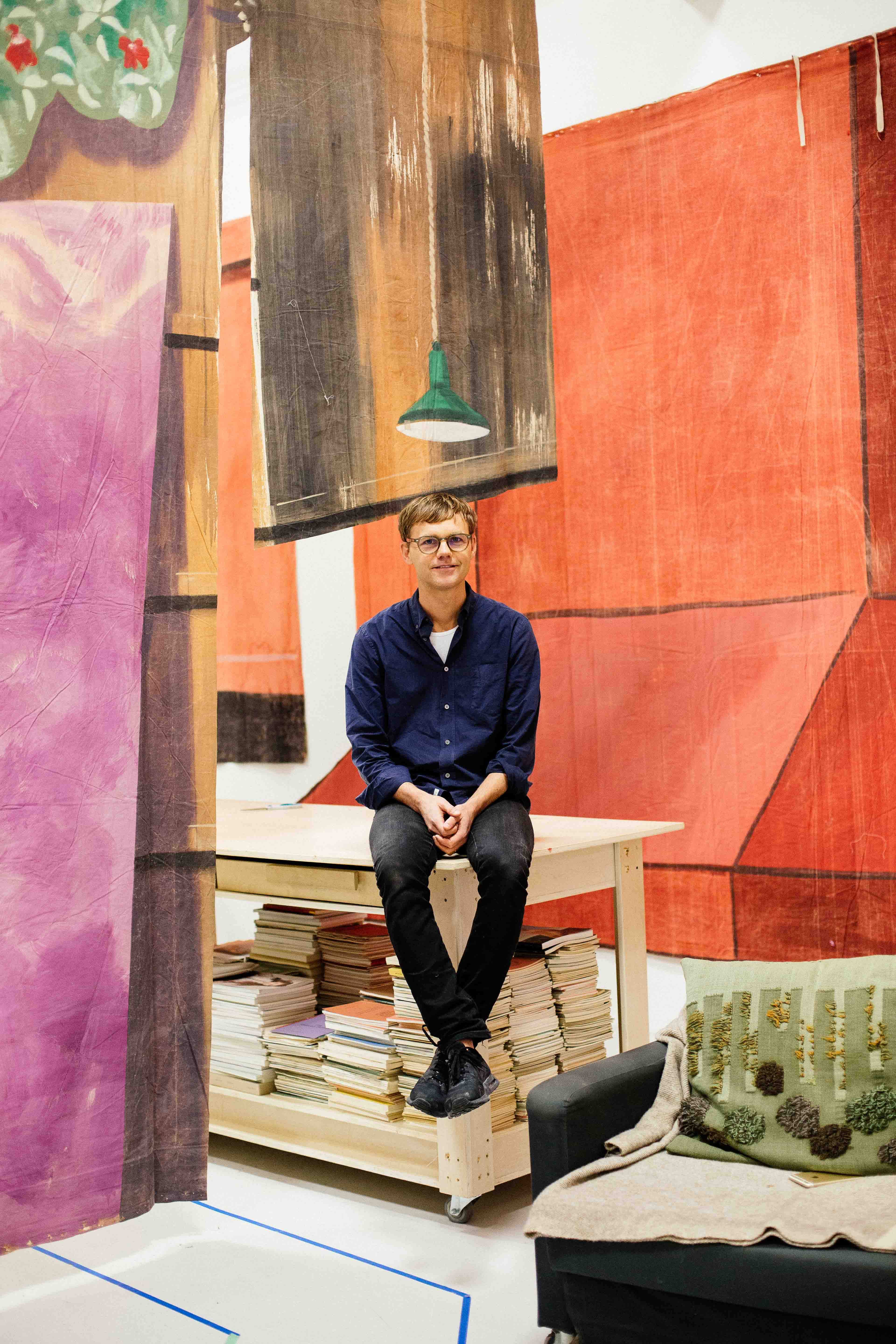

In fact, the 49-year-old has filled one of the double-height walls of his East Vancouver studio with a mounted display of used brooms, several of which were collected during his global travels. (Farmer gives new brooms to workers he meets in exchange for their worn-down ones. He has collected about 150.) Farmer’s incense-washed studio has a mad scientist vibe that makes it easy to overlook oddities. A long desk is covered with hundreds of printouts and a set of black 3-D–printed flies of various sizes. A library at one end of the space is crowded with books by the likes of Bauhaus, Brancusi, and Braque. A desk along one wall seems to be set up for experiments with a Chinese calligraphy brush. Farmer’s computer is ringed with dice, models of a turtle and a praying mantis, more flies…

I pick up a fly and ask what it’s made of. Instead of telling me that the 3-D printer has produced the sculpture out of nylon, though, Farmer begins talking about the original object that he scanned—an antique ashtray. “You could lift up the insect’s wings and ash inside its body. And look,” he lifts the model’s wings. They’re perfectly hinged, just like those of the original, which I never get to see.

Farmer has built his career by cutting things out of their original context, and the fly is no different. The shape and meaning of the original antique have been cut away from the material fact of its body. We are left with the idea of the thing itself—a shadow you can hold.

The “cut-out king” came dramatically to the public’s attention in 2012 when he assembled a monumental work called Leaves of Grass for that year’s prestigious Documenta festival in Kassel, Germany. Sixteen thousand figures were meticulously cut out of roughly 900 Life magazines dating from 1935 to 1985. (Nearly 100 people worked on the project, many of them volunteering their time during a gruelling work schedule leading up to the opening.) These cut-outs were then reassembled as a 124-foot-long menagerie of “stick puppets,” each suspended atop a stem of dried grass. The result was an enormous piece of “sculptural theatre” (in Farmer’s words) that became an immediate favourite among the nearly 1 million festival visitors. The effect—cacophonous, marvellous, and decidedly pop—was a testament to the magazine-glossed spirit of the United States of America. Just as Walt Whitman’s book of the same name was intended to capture the spirit of a people through a big, lusty voice, Farmer’s Leaves of Grass plays off the high-voltage spirit of a country, even as it divorces those images from the tightly controlled context of Life magazine.

Indeed, part of what Farmer’s work accomplished—besides bowling over the Documenta visitors—was that it set free all those celebrities and politicians and animals. It proposed that content be unbound from the prison of its original technological container.

Farmer had proposed just such a freeing in 2007 when he built The Last Two Million Years (it has since been acquired by London’s Tate Modern). For that work he cut out every image from a 500-page Reader’s Digest anthology of human history by the same name. The year after his Documenta triumph, Farmer presented The Surgeon and the Photographer at London’s Barbican Centre. (The work actually took three years to create, but was completed in 2013.) There, his hundreds of figures (each composed of fragments cut from books and magazines) became an expression of the multiplicity of life itself. Each of the figures contained a multitude of identities and attitudes in itself, variously expressed as the viewer walked around them and glimpsed cues from different angles.

The “cut-out king” came dramatically to the public’s attention in 2012 when he assembled a monumental work called Leaves of Grass for that year’s prestigious Documenta festival in Kassel, Germany.

In this trilogy of “sculptural theatre”, the labour involved in Farmer’s practice is decidedly (and sometimes obsessively) evident. I remember walking into a room at the National Gallery of Canada, where Leaves of Grass was being installed following its Documenta run. The piece was half up and three workers were seated along the far wall, busily constructing the remaining figures. While not strictly part of the work itself, the evidence of labour, the understanding that so much care and attention had gone into the piece, was something I couldn’t shake.

Sometimes, however, the labour that goes into “cutting things out” is hidden. Consider the 24-hour-a-day video display called Look in my face; my name is Might-have-been; I am also called No-more, Too-late, Farewell, a work created in 2013 that Farmer later installed in Toronto’s Trinity Bellwoods Park for the 2015 Luminato festival. Thousands of sound clips gathered from libraries and archives spilled out of speakers while images scanned from books and magazines scrolled across the screen. Run off a Mac mini, the work might be mistaken for a random assemblage, but the “cut-outs” it displays are actually chosen by an algorithm that selects content depending on a variety of inputs, including time of day—a responsive, relentless flow of visuals and sounds that, for Farmer, shows “the world wanting to reveal itself.” The images are all sourced from pre-Internet objects (old books and magazines), rather than digital files, which “lack a material quality,” Farmer points out. He thinks of the resulting work as a fountain, a screen with the ability to pour out an endless, ever-renewing stream of content. “I wanted to make a work where the labour is hidden,” he explains to me. “Something where you aren’t thinking about the work that went into it.”

Whether the labour is visible or not, Farmer’s strategy—cut it up and free it from its original technology—has charged his viewers and deeply excited the art world. Beyond blockbuster appearances at the Louvre, the Tate, and Documenta, beyond the critical acclaim and international demand for his work, Farmer’s rise to fame in the past few years has been fuelled by that rarest sort of alchemy: the combination of institutional acceptance and popular love. Folk who claim to “know nothing about art” often step away from his installations with as much to say as the intelligentsia.

The story of how an artist rises to such popularity is always a kind of fib—our artists do not spring, fully formed, from pods; nor are they called into existence by Artforum. But the notion of an “inciting incident” still bounces around. And, depending on when a journalist sits down with Farmer, they might hear a different story. Perhaps it was the art class at Kwantlen College that his sister was taking—he got to sit in on it, started drawing, and heard a bell go off in his head. Or else it was that time on a train when he was collaging/doodling in a journal and a stranger asked, “Are you an artist?”

There are some facts. Farmer grew up in West Vancouver and had no particular plans to become an artist. After the mysterious “inciting incident”, he studied at the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design in Vancouver (graduating in 1992) and did an exchange at the San Francisco Art Institute, too (1990–91). But at school, Farmer didn’t quite fit in; he was unsure of his own powers and didn’t much identify with the kids who “knew” they were artists. Even today, he remains boyish-looking, with blond hair and blue eyes. His presence is so disarming—so cheerful and kind—that you are forced to remind yourself about the grandeur of his position in the international art world. (He’ll gossip about gay Instagram feeds as happily as he’ll chat about the history of minimalism.)

No pretence of seriousness or erudition was required for him to become successful. Farmer’s work—at once magnificently fresh and jokingly aware of its place in the history of art—could always speak for itself. By 1997, only a few years out of school, his rise had become meteoric. His first significant solo show took place in 2000 at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and he debuted that same year at Vancouver’s Catriona Jeffries Gallery, which has represented him ever since. (Farmer is also represented by Casey Kaplan in New York.) Over the last 15 years, dozens of solo and group shows have cemented his reputation. Media at first lauded him as part of “the next generation”, “the new school”, and “future greats”, but as early as 2005 he seemed to ascend and become part of the art world’s firmament.

Farmer does not love the fame. At his studio, sipping a second coffee, he shrinks an inch when I bring up a magazine that said his career was in “warp-drive mode.” “There’s a disconnect,” he says, “between what people read about me in magazines and my experience. In the last three years, I’ve worked more and been more exhausted than I ever have. And I’m so involved in the making of the work that it doesn’t feel like what they show in the magazines at all. There’s just this uncertainty, this feeling of not knowing what you’re doing.” When he completed Leaves of Grass, for example (perhaps his most lauded work), he was convinced he had produced a failure. He was $50,000 in debt, nervous, and dejected. When the work began attracting such universal praise, he was taken aback. “There’s this fantastical picture that gets created,” Farmer says, “but all that is obliterated by the realities of life, the way life humbles you and knocks you onto your knees.”

“I want to take a leap into new territory,” explains Farmer of his Venice Biennale artwork, which remains very much a secret. “There’s such an opportunity for failure. It’s nerve-racking.”

Part of the curse of fame for artists like Farmer is that the public demands a crystallization of their practice—and the public wants repeats of blockbuster works at factory-efficient speeds. But Farmer is “a fern, not a cactus,” he explains to me. “I need shade and maybe five years between things. And then, when things do finally happen… Well, it’s like a thunderstorm, you know? You can’t force a thunderstorm to happen.”

How does a fern make a thunderstorm? Such was the anxiety at play when Farmer took a phone call from the National Gallery last December. He thought it would just be another query about the conservation of his work but, instead, it was director Marc Mayer asking, “Do you want to do Venice?”

“I said yes right away,” Farmer says. Yet there was dread, too. “When I agreed to it, I was thinking I need to use this opportunity to shift the way I work. I want to take a leap into new territory.” The Canadian pavilion at the Venice Biennale is notoriously awkward—hexagon-like, disorienting, and small. But because it’s being restored just after the 2017 edition, the Italian authorities have given Farmer certain liberties with the space. Still, he says, “There’s such an opportunity for failure. It’s nerve-racking.”

Farmer’s Biennale work, still untitled and still very much a secret, will not be a cut-out extravaganza in the style of Leaves of Grass. And yet it will still be a metaphorical “cut-out”—the methodology’s spirit remains. A while back, Farmer’s sister found a couple of black-and-white photos of the scene where their grandfather was killed. They show a railway crossing, a pickup truck knocked off balance, a ruined fence. He saw his opening. It is this miniature personal archive, some photos of no consequence to anyone but Farmer’s own family, that will serve as source material for the Biennale work. (Indeed, a central axis point in the pavilion will become an allegorical re-creation of the event.)

To push his art further, Farmer has also decided the “cutting out” will, this time, not be done by his own hands. In fact, the work is being produced at an art foundry in Switzerland called the Kunstgiesserei. There, 3-D–printed sculptures are being cast in aluminum and bronze. Farmer sees those printed sculptures as a natural evolution of his earlier work. When he was cutting images out of magazines, he was freeing them from the page. When he prints 3-D sculptures, he is freeing shapes from their original containers, too. The objects, seemingly spun from the air, are also shadows, echoes of the original. “Looking at a 3-D–printed object, there’s this uncanny feeling you get. It’s similar to when people saw a train coming toward them on film for the first time. They ducked. They didn’t know what they were seeing. That’s what’s happening to us now.”

The advent of 3-D printing, of course, has serious repercussions for the manufacturing industry. What happens to that labour when, instead, we can press a button and 3-D print a table, a T-shirt—or a piece of art? Farmer seems at once entranced and appalled at the ease of mechanical reproduction. But by cutting things out of their original context, his work forces us to notice the labour behind creation. As he tells me about his plans for Venice, his fear of failure, and the “embarrassing labour and mistakes” that take up so much of his days, that wall of ruined brooms rises over his shoulder like a silent chorus, like so many witnesses to that labour, that care.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter.