An Excavation of the Victorian Mind

The cult of beauty.

The teapot from Christopher Dresser’s tea service set, 1880. Photo ©V&A Images.

That spherical, spiky steel object could be orbiting Earth. Instead, it stands near a serene portrait by James Abbott McNeill Whistler and an elegant cabinet by English architect-designer Edward William Godwin. This is not a random conjunction, as a wall sign explains. In defining aestheticism, it makes the connection between “something that looks like a medieval manuscript and something resembling a Sputnik,” says Dr. Lynn Federle Orr, curator in charge of European art at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. (That round, spiny “Sputnik” turns out to be a 19th-century teapot designed by Scots-born Christopher Dresser.)

Now showing at the Museums’ Legion of Honor until June 17, “The Cult of Beauty: The Victorian Avant-Garde, 1860–1900” is the first major exhibition to explore the groundbreaking creativity of the British Aesthetic movement in which a coterie of painters and poets seeded a trend that affected a large part of their contemporary life.

Instigated by Dr. Orr, a long-time lover of Victorian art, and organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco in collaboration with the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, the exhibit brings together a stunning collection that, depending on the location, has appeared under different names. London called it “The Cult of Beauty: The Aesthetic Movement 1860–1900”; Paris racily referred to “Beauty, Morals and Voluptuousness in the England of Oscar Wilde”. Dr. Orr acknowledges a lot of debate: “I always wanted ‘The Victorian Avant-Garde’, ” she says, appreciating the sly contradiction of straitlaced and subversive. And coming hard on the heels of Victorian fuss and clutter, this new movement was most definitely subversive.

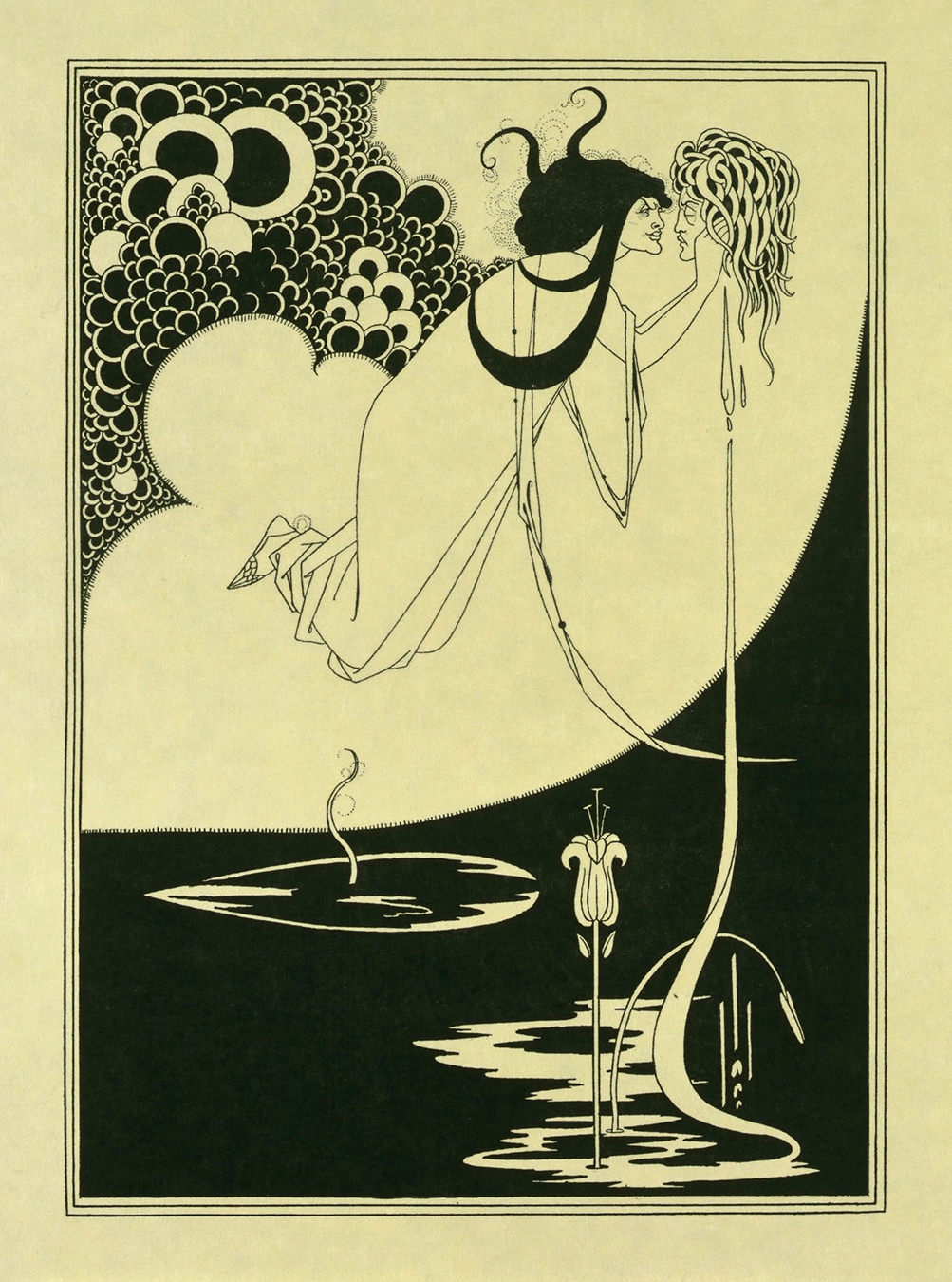

Aubrey Beardsley’s print The Climax, produced for Oscar Wilde’s play Salome, 1894.

Its creators turned their talents from paint and poetry to replicating the idyll in real rooms and furniture, beginning with their own surroundings. It was “the first time so widely encompassing a movement had entered the mainstream,” says Dr. Orr. From William De Morgan’s peacock-embellished ceramics to early self-help books and comfortable fashions, the trend shaped everyday living. Cabinetry, art photography, William Morris’s distinctive wall coverings, and Aubrey Beardsley’s drawings, the exhibit represents the cream of the aesthetic A-list and includes works by Whistler, John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, and Dresser that belong to the San Francisco Museums.

It’s apt that the City by the Bay is the sole North American “Cult of Beauty” venue, as Oscar Wilde (who, Dr. Orr concurs, could be called “the Martha Stewart of his day”) lectured there in 1882 for a crowd of 4,000. Parallel with the exhibit, related events include a partnership with local wallpaper and textile company, Bradbury & Bradbury, and the Jean Paul Gaultier exhibit seen in 2011 at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts that asks the question: Just what is avant-garde?

So was the Aesthetic movement a trend that lasted? Let’s just say that, over a century later, design leader Alessi still produces some of Christopher Dresser’s stunningly simple pieces.

Photos ©V&A Images.