Scalawags: Slim Gaillard, Satin-Smooth

We got the beat.

Slim Gaillard told a lot of stories about himself and he told them well. As is the case with many such storytellers, especially ones who’ve been around, he had his doubters and detractors. A person with nothing else to do might come up with a mathematical formula to prove that the better the raconteur and more varied the life from which the material is drawn, the more doubt cast upon the stories.

So just imagine Slim in his satin-smooth voice saying, “Jack Kerouac? Yeah. In San Francisco, him and me got all the women ‘cause we were the best looking cats around. Long ago, Jack wrote about me.”

And there’s On the Road to prove it: “One night we suddenly went mad together again; we went to see Slim Gaillard in a little Frisco nightclub … crowds of young semi-intellectuals sat at his feet … he does and says anything that comes into his head …. Now Dean approached him, he approached his God; he thought Slim Gaillard was God.”

Or Slim saying, “Marlene Dietrich? Yeah, she dug what I did.” And there’s a recording of The Bob Hope Show. Bob: “Say, Marlene. Do you know this Slim Gaillard?”

Marlene, unrehearsed, saying, simply, “Vout.”

Say what?

Slim claimed to have been the first person to speak the word “groovy”. Lexicographers might dispute the point but not that he invented the language of Vout. There was a lot of what was known as “jive talk”, starting in the 30s and lasting until the lyric and language-challenged rock and roll era, and people like Harry “the Hipster” Gibson, Babs Gonzales and Leo Watson performed linguistic acrobatics but none flew so high on that trapeze as Slim Gaillard. He wasn’t just inventive, he was surrealistic.

How’d this hip, scalawag-ish wit get that way? It would be too easy to ascribe his love of the word and all its possible permutations to a checkered background. All that did was provide raw material. Bulee “Slim” Gaillard, was born that way, with the predilection. Where that birth took place is open to question. Most biographical dictionaries of jazz claim Detroit as the place. Slim said Santa Clara, Cuba. It is true that he travelled on ships with his father, who was a steward. Slim told stories about how, when he was 12 years old, he got left behind in Crete. Before he started in vaudeville as a tap-dancing guitar player, Slim was a boxer and a mortician’s assistant. He claimed to have worked in speakeasies owned by Al Capone, who was always nice to him, as he was to other musicians.

In the early 30s, he went to the famous Brill Building to audition for agents in search of “professional amateurs”. You had to sound bad enough to convince audiences you were an amateur while simultaneously being good enough to hold their interest. All the people hired made a circuit of vaudeville theatres and radio shows, like Major Bowes’ Amateur Hour.

Gaillard remembered, “I would be a tap dancer one week, play the guitar the next, boogie woogie piano the week after that.” Slim’s biggest hit number, recorded in 1938 with bassist Slam Stewart, was “Flat Foot Floogie”. Nowadays, this tune, both cool and madcap, is known only to old jazzbos, explorers of realms that shouldn’t be obscure, and fans of Jack Kerouac who happened to see the documentary about the writer, which includes a video clip from The William Buckley Show. The host with his usual supercilious air, asks his guest, who, for all intents and purposes appears to be asleep, a ridiculous question about the origins of the hippy movement. Kerouac opens his eyes, looks at Buckley and sings a reply; “Flat Foot Floogie with a floy floy.”

“‘Flat Foot Floogie’”, Gaillard recalled, “came from a riff I used to play on Major Bowes. Then Benny Goodman played it and soon everybody was singing it.” Gaillard and Stewart, known as Slim and Slam, had other surrealistic jazz hits, like “Vol Vist du Gaily Star”, “Chicken Rhythm” and the original “Tutti Frutti”.

After the Second World War, during which he served in the famous, segregated, black squadron of the Air Corps, Gaillard got with another great bassist, Bam Brown, and there came more hits, particularly, “Cement Mixer (putt-ee, putt-ee)”. Slim and Bam were booked for a two-week gig at Billy Berg’s Club in Hollywood, and stayed for a year. “Vout”, also known as “Vout Oreenie”, became so popular, even Ronald Reagan, according to Slim, was talking it.

One night or early morning, Slim went to an Armenian restaurant and was intrigued by the menu, the writing on which he couldn’t understand. He copied the words into his notebook, went home and put them to music. The result was “Yep Rock Heresy” which was so downright unusual that the squares figured it had to be “degenerate”, and probably “communist-inspired”, as well. Thus, the song was banned from several radio stations, and Slim had another big hit. In 1945, he recorded a song called “Genius” on which he sings, plays trumpet, trombone, tenor saxophone, piano, organ, bass, drums and taps dances in rhythm. The next year he composed a twelve-minute “Opera in Vout” that was recorded live.

In the late 40s, in North America, a mad rush to the suburbs was on; jazz got cool, bop hard, and Slim only worked sporadically. In the early 50s, he was showing off solid musicianship in gigs at Birdland with Billy Taylor and Art Blakey. He made some recordings with Norman Granz but by the late 50s he was back to scuffling. He quit the road after a tour where he had to open for Stan Kenton. Which calls to mind, Art Pepper’s comment in his autobiography, Straight Time; “I took a gig with Kenton until something came up in jazz.”

Gaillard used to frequent a Hollywood restaurant in the mouse hours, to talk with other musicians and dig the comedians telling jokes that they couldn’t use in their acts. He was approached by an acting agent, who got him to read for a part. With music gigs scarce, Slim became an actor, appearing in television series and in John Cassavetes’ Too Late Blues. Later he was in Roots.

He continued to play an occasional music gig until the early 60s when the British Invasion and the subsequent Age of Aquarius put him out of work. Gaillard managed a motel in San Diego and eventually bought an apple orchard in Tacoma. For twenty years, the only time Slim appeared on a recording was with his son-in-law Marvin Gaye. Two of those hands clapping on cuts of “Sexual Healing” are Slim’s.

Early in the 80s, Dizzy Gillespie visited Slim in his apple orchard, and began a campaign to get him back into music. Dizzy convinced the promoter George Wein to engage Slim, and the result was a summer on the European festival circuit. Then came a steady gig in the Patio Bar of the Meridien Hotel in Paris. In 1983, he went to London for a two-week date and to record an album with Buddy Tate and Jay McShann. “And I wound up staying.”

It was the return of Slim Gaillard. “I got that old music feeling again.” He played all over Europe, appeared with rappers on their recordings, had a bit in a terrible movie called Absolute Beginners and was the subject of a four-part BBC documentary series. He died of cancer in 1991.

So what made him so hip? It isn’t just that he seemed to be able to do everything. It was the way he did it. He was assured and smooth but never, ever arrogant. The very idea of anyone else trying to do that record “Genius”, would be offensive. Often considered, unjustly, a comedy act, Gaillard was a terrific musician and great singer. For every so-called novelty number there was a serious soulful one, like “Mean Mama Blues” or “Boot-ta-la-za”.

One of my favourite Slim cuts is “Slim’s Jam” featuring Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Not only is there a devastating solo by Parker but a display of Slim’s adlibbing in Vout. At one point, Dizzy says he has to go make another gig, to which Slim replies, “Oh, I was just going to order in some avocado seed soup.”

This cut also offers a rare incidence of Bird talking to a peer. Slim saying, “Why there’s Charlie Yardbird.” There’s a whole lesson in cool to be derived just from the way Slim phrases that sentence, the way he stresses the “Yard … bird.” Bird replies, “Hey Slim. What’s happening, Jim?”

And, by the way, a pure glimpse of hip is Parker’s solo, which copies and extends that of tenor saxophonist Jack MacVie, a great solo in itself from which Parker squeezes that one remaining drop of, what? Soul. It is sexual is what it is. And in case one has not picked up on that, there’s Slim, exclaiming, “Unnhhh!”

Maybe that’s the thing with Slim Gaillard, an ever-present, behind-the-beat sexuality that underlined everything he did. Whether he was singing, dancing, playing eight instruments, being funny or inventing new language, he conveyed, without insinuating, the sexual content of things.

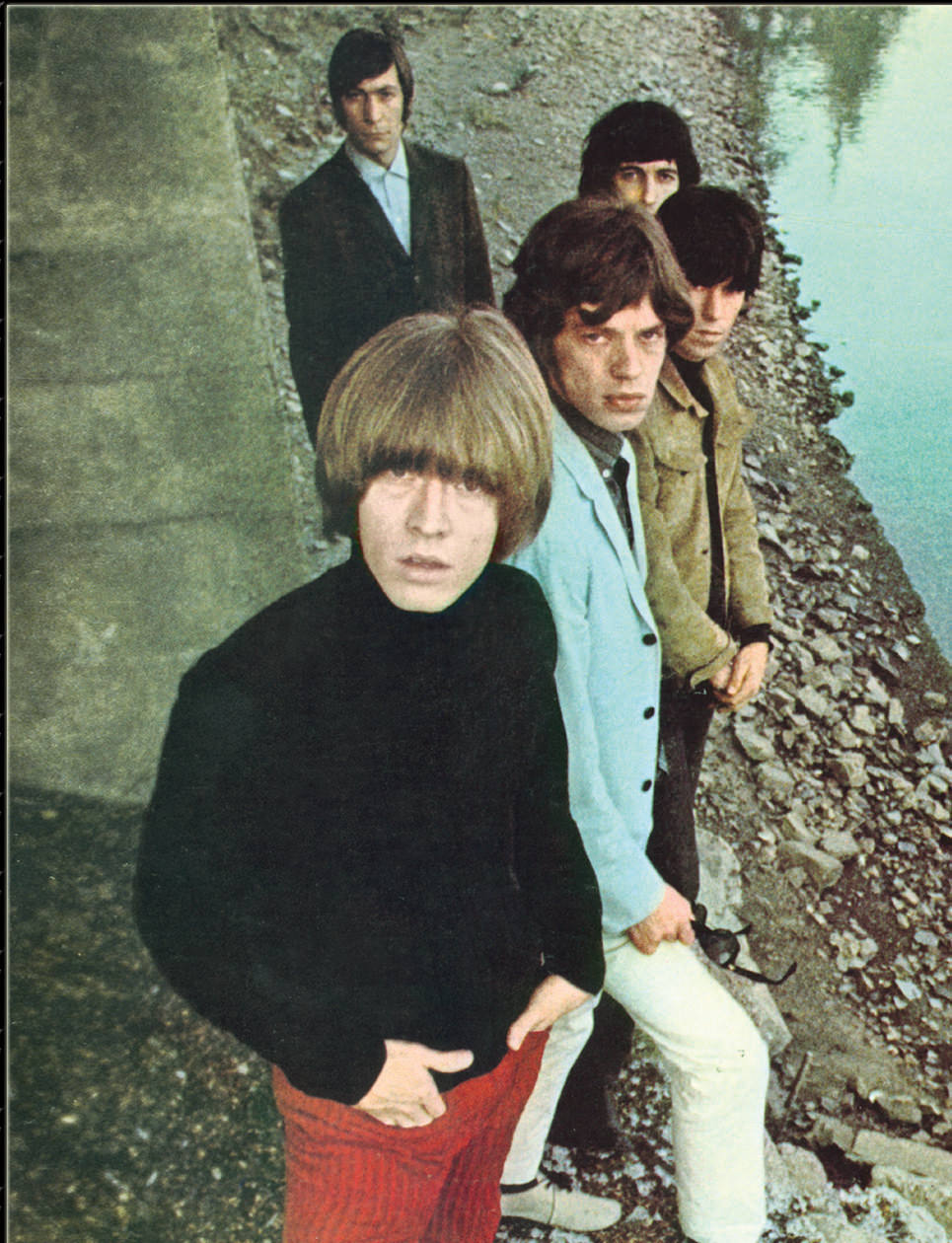

Photo: ©CORBIS/MAGMA.