Jennifer Carvalho in her studio. Photograph by Colin Outridge.

Archival Echoes: The Art of Jennifer Carvalho

The Toronto-based artist excavates hand gestures, jewels, and tears from Renaissance artworks—liberating them from their original context to reveal a present-day resonance.

The Unicorn Rests in a Garden is one of the most beguiling masterpieces bequeathed to the modern world from medieval Europe. Finely woven from wool and silk fibres, with some gilded threads, it is part of a group of seven panels known as The Unicorn Tapestries, which hang at The Met Cloisters in New York. It is believed that the intricate tapestries were made in France and the Southern Netherlands between 1495 and 1505, but nobody knows by whom or for what reason. Some say they celebrate a marriage. Others posit their purpose as a teaching aid for Christian allegory. As scholars debate the context and meaning of the works without consensus, curators prune back the works’ accompanying didactic panels to paucity. At present, the museum provides just one sentence for each scene.

Toronto painter Jennifer Carvalho’s study of the work, An archive of gestures (garden enclosure), 2025, might be the most extreme excision of the original yet. In her precise rendering of the weaving in oil on canvas, which measures five by six and a half feet, Carvalho has faithfully recreated each stem, stamen, petal, and pistil of the flowers growing in the artwork’s verdant enclosed garden—but the unicorn itself, a symbol so relentlessly scrutinized and saddled with projected meaning, has vanished without a trace.

“We’re given only fragments of information,” Carvalho says about the art historical record. Like an archaeologist, she excavates pieces of artworks made in Europe from antiquity to the Renaissance. Most of her source material comes from replicas she finds in books or on the internet. She tweezes out the elements that interest her, dusts off their original contexts, and jigsaws them into enigmatic new compositions. Outstretched palms, furrowed brows, clasped fingers, and tear-stained faces are among Carvalho’s most collected motifs. “How am I to read these gestures?” she wonders of the disembodied remnants. “What is the malleability of them? How can they be read by a contemporary audience? What is still recognizable to us today?”

Jennifer Carvalho, An archive of gestures (garden enclosure), 2025, Oil on canvas, 60 x 78 inches.

Born in 1980, Carvalho grew up in a Catholic family of Portuguese descent in Hamilton, Ontario, and remembers her first experiences of art being related to religious imagery. “I was always secular in my thinking,” she says, “but I was also in this ideological world that I was really interested in. I loved the ritual of church and all the pageantry. But I had a lot of questions and wanted to unpack it and understand it. Where did this come from? Why? What is the history of this? Why are we doing this?”

Her parents were always supportive of her artistic talent, enrolling her and her little sister in art classes and giving them paint and brushes for birthdays and at Christmas. “There’s this funny story in my family that my mother was taking figure-drawing classes at a local college in Hamilton, and I, as a child, came across these drawings and drew clothes on all the nude figures,” Carvalho says with a laugh. Another time, she remembers stumbling upon some copies her mother had made of historical paintings: “these really lovely, little quiet drawings,” she says. Even back then, as she is now, Carvalho was drawn to investigating the past and remixing the work of others.

Attending McMaster University in her hometown, Carvalho studied art, art history, and English literature, and ended up with two undergraduate degrees. She moved to Vancouver and started mingling with people in the contemporary art scene, going to gallery openings, and becoming friends with students from Emily Carr University of Art and Design. It was the painter Elizabeth McIntosh who suggested that Carvalho reach out to faculty at the University of Guelph about pursuing a master’s degree in fine arts.

By 2011, Carvalho was enrolled in the program at Guelph, in a cohort that included the artists Nadia Belerique, Jenine Marsh, Laura Findlay, Jen Aitken, Patrick Cruz, and her now-husband and gallerist, Aryen Hoekstra. She remembers feeling “green. I had been making this figurative work, but I couldn’t really articulate what I was doing and why,” she says of her practice at the time. “I had this complete change before my very first critique and started working with landscapes.”

As a result of this volte-face experiment, Carvalho developed a fascination with cinematic framing. “I became really interested in thinking about how the long take functions as this slowing down of time,” she says. She names Andrei Tarkovsky’s famously slow-paced 1979 science-fiction film Stalker as a major influence. “You’re almost having to work through boredom,” she says, laughing about her reaction to the plodding camerawork. “I was really, really excited,” she says. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve watched Stalker.”

Most movies use rapid cuts to keep viewers’ attention, but some of the shots in Stalker exceed four minutes. “The narrative starts to fall away, and you allow your eyes to wander along the surface,” Carvalho says. “You start to pick up on the materiality of the film.”

Tarkovsky’s technique inspired Carvalho to try to create the same unhurried effect in her work. “I structure my paintings in a way that they’re all over in terms of the amount of detail,” she says. While her subject matter might mimic the work of Northern Renaissance masters such as Jan van Eyck, her method is entirely different. “I am working with opaque paint and building almost like a scumbling,” she explains, referring to a process of brushing thin, dry layers of paint to create a hazy, textural surface. “It reads almost like fresco,” she says, comparing her canvases to pigment applied directly to walls.

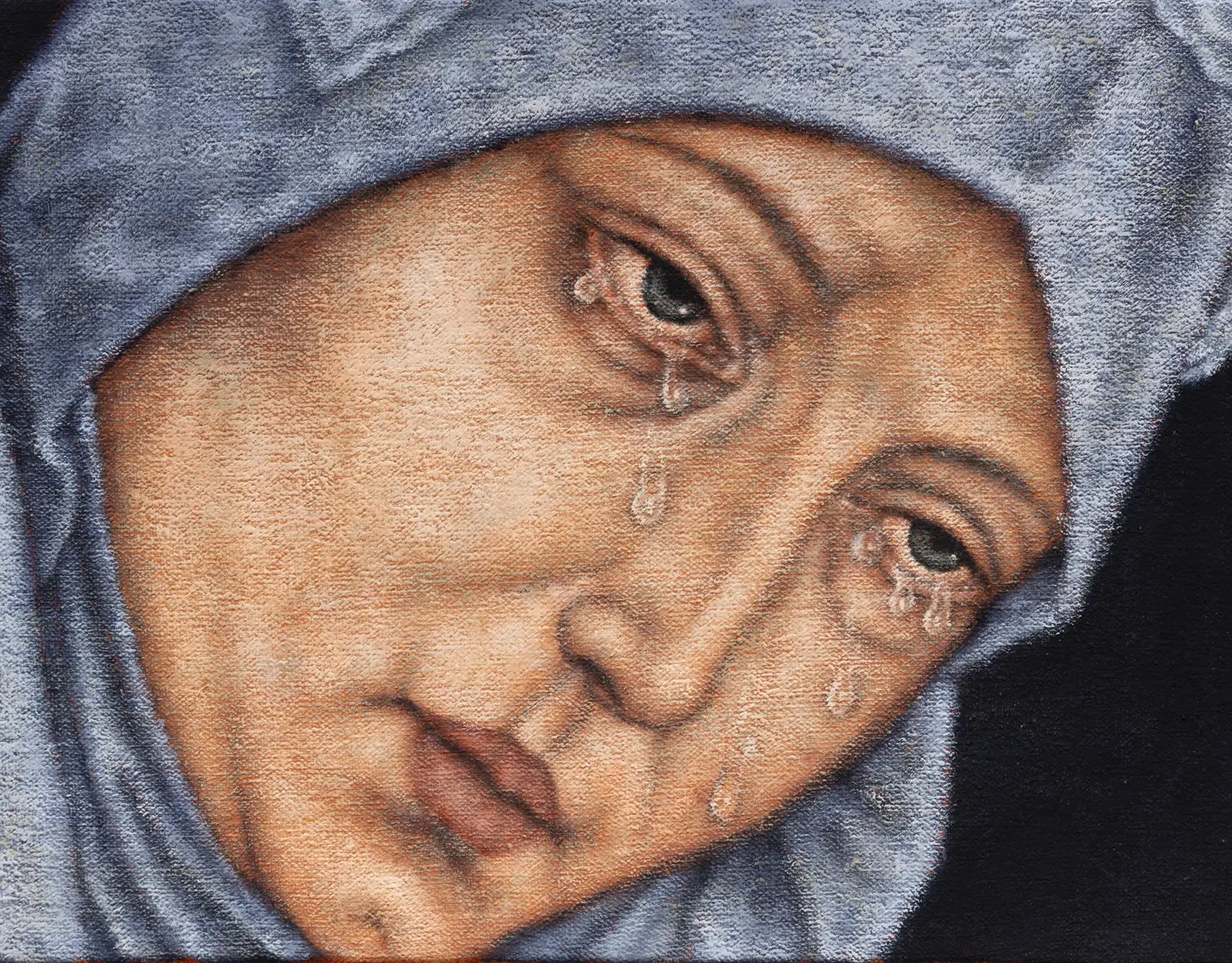

Jennifer Carvalho, Crying woman (Marmion), 2024.

“They’re not trying to replicate flesh,” Carvalho says of her paintings. Unlike her historical forebears, her intention is not to hoodwink the viewer with the uncanny luminosity of a jewel, the realistic iridescence of pleated dupion silk, or the smoothness of a noblewoman’s cheek. Instead, she thinks of her work as “this thing that has this age and has travelled through time, that is carrying things with it,” she says, evoking the image of a wizened voyager from the past, laden with curious souvenirs and unfamiliar concepts.

European art produced from antiquity to the Renaissance has especially fascinated Carvalho because “It’s like the beginnings of the world that we live in now,” she says. “It’s just far away enough that it feels very much of a different time, but we can kind of see it. It contains the seeds of the contemporary world that we live in, in terms of our ideologies and capitalism.”

___

“There’s this constant human tendency to look back to understand the present through the past. How do we take stock of what we have and what kind of world we want to see moving forward?” —Jennifer Carvalho

Carvalho has been greatly inspired by the ideas in Italian American author Silvia Federici’s 2004 book Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Federici applies a Marxist-feminist lens to the history of the transition from feudalism to capitalism in western Europe, arguing that the oppression of women’s bodies—and their mass murder carried out under the auspices of witch-hunting—was essential to the ascendancy of the world order we still live under today.

By liberating the fabled unicorn from captivity, Carvalho snaps the background of the artwork into focus. “There are paintings in antiquity of these fantastical gardens where you can identify the different plants and animals, but everything’s in bloom at once, which is impossible,” she says of the utopic tableau.

Carvalho points to the garden’s circular pen, now unoccupied, and explains, “I’m thinking about the early modern period as being the shift to early wage labour and the enclosure of the common lands. What happens when I remove something? Then how do we read this information?” While the mythical beast (which was believed to be real at the time of the artwork’s creation) is no longer chained to a tree, this is still an image of incarcerated innocence.

Jennifer Carvalho, Still being (seat of wisdom), 2024.

Jennifer Carvalho, Faithful observation (study of touch), 2024.

The painting inspired by The Unicorn Tapestries was a central element of Carvalho’s recent exhibition at the Centre for International Contemporary Art in Vancouver, her first solo institutional presentation. Here, as in Ghost, her fall 2024 show with Franz Kaka in Toronto, Carvalho also included a painting that zooms in on the faces of grief-stricken holy women whose eyes dribble waxy tears. Three similar works will feature in her solo show this September at Cylinder in South Korea, which is also bringing her work to Frieze Seoul.

“I started thinking about them as being like a Greek chorus,” Carvalho says of her mourning women, “or a Shakespearean play, where there’s an actor that is discussing what’s happening within the play to the audience, speaking directly to you.”

The crying faces are inspired by figures from paintings such as Rogier van der Weyden’s The Descent From the Cross, ca.1436, but because the women are removed from the context of Jesus’s crucifixion, the source of their anguish isn’t so immediately apparent. “I think they could speak to a contemporary feeling of anxiety,” Carvalho says. They also point to lingering dogma about what kinds of bodies are allowed to show what kinds of emotions. “I’m open to them doing a lot of different things,” she says.

At one point during our interview in Carvalho’s studio, a bee flies into the room and lands on her hair. Lately, she has been keeping the window open because it helps her paint dry more quickly, which means she can work on five pieces at once, building up each image thin layer by thin layer. For a few minutes, I try, awkwardly, to capture the bee using a water glass, but fail abysmally. Then, ever so elegantly, Carvalho swoops in, cups her hands around its buzzing body, and gently directs it back to the ledge and out of the window, and it is gone. I clasp my hands together in appreciation.

Jennifer Carvalho, From gold to brush (study of optics and splendour), 2024.

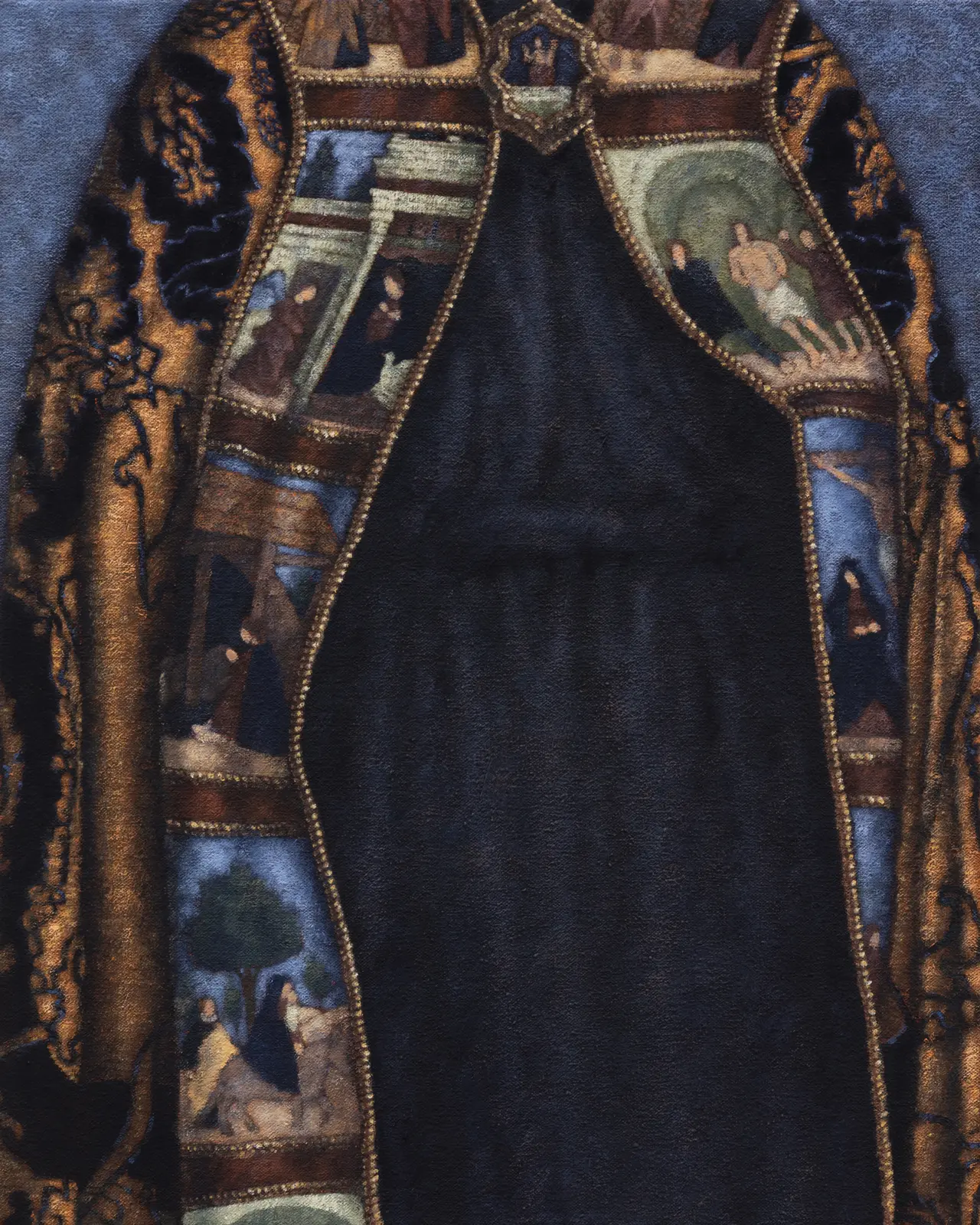

Jennifer Carvalho, Cope and stole (study of ceremonial attire), 2024.

Jennifer Carvalho, Marks of ancestors (monument with figures removed), 2024.

Our hand gestures, divorced from their context, might otherwise be read as declarations of modesty, or the bestowing of a blessing, or even, to a conspiracy theorist, possession of occult secrets. As for the bee, it has been variously regarded in art as “hard-working, helpful, tidy, chaste, docile, virtuous, wise, obedient, and invested in the common good, but also as both defensive and aggressive,” according to the 2025 Museum Wiesbaden exhibition Honey Yellow: The Bee in Art.

“It’s another framing device,” Carvalho says of the placement of hands in Renaissance painting. “There are paintings that are literally pointing to what you’re supposed to look at. There are figures pointing at other figures and being like, ‘Look over there!’” she says, laughing. “We see that continuation in cinema and film, through the way that we frame a subject. You know, we’re being told how to think about something, how to understand it.”

We can’t ever really know how people in the Renaissance read the semiotics of the artworks they lived alongside. Not enough has survived to give us a full picture. “It’s so costly to conserve paintings,” Carvalho acknowledges, but she is grateful when she sees such efforts. “I love those moments of intervention, where you see these little lines of somebody adding information to where there is loss, and that accumulation over time,” she says. She recounts a “wonderful” hour she spent reviewing a deteriorating painting under the light of cellphones with the assistant curator of European art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Adam Levine.

Jennifer Carvalho, Flying figures with garden, floral motif, and frame, 2024.

“There’s this constant human tendency to look back to understand the present through the past,” Carvalho says. “What’s worth keeping? What do we leave behind? How do we take stock of what we have and what kind of world we want to see moving forward? We’re learning in real time that you can’t forget about the past. You do need to constantly be reminding yourself of what has happened.”

In The Unicorn Tapestries, a monogram incorporating the letters A and E and a knotted rope is prominently and frequently featured. This was a detail that Carvalho opted to retain in her study. I ask her what the letters mean, and she says that no one has been able to figure that out. “Maybe if there was more information in terms of these initials, it would have been too specific for me, and I might have removed it,” she says, “but because it is a question mark, I wanted to keep it in.” I take one last look at the canvas before I leave Carvalho’s studio, and spot a bee hovering over a flower, half of its body camouflaged by a fence post. How strange that I hadn’t noticed it until now.

Photographs courtesy of the artist and Franz Kaka, Toronto.