Artist Sergio Fiorentino Translates the Charm of His Noto, Sicily, Into Gripping Paintings and Artworks

Blue dreamer.

Blue dreamer.

Noto never fails to stir emotion. The small town in southern Sicily is an architectural jewel—so much so that UNESCO added it to its World Heritage list as a site of outstanding universal value. A stroll down Corso Vittorio Emanuele, the main street, leads visitors past churches—notably the imposing Cathedral of San Nicolò and its grand staircase—palaces, fountains, and theatres embellished with grinning masks and putti, sacred cherubs depicted as chubby male children with wings. Noto is a masterpiece of baroque architecture, and while fascinating at any time of day, it is particularly compelling at dusk when the buildings take on a golden colour as the tufa stone absorbs the brilliant Sicilian sun throughout the day and emits it at sunset. This town of fewer than 25,000 residents captured the heart of collector-turned-artist Sergio Fiorentino, who now lives and works in the reimagined 18th-century refectory of a former convent.

“For me, Noto was a strong stimulus in changing my life’s path,” says the 50-year-old artist who, after formal schooling in art and antiques restoration, detoured into dealing in modernist design before moving to Noto to take up painting 12 years ago. Fiorentino was born in Catania, an hour’s drive from Noto, but he admits, “it was not a place I frequented. I am still not exactly certain what transpired.” He explains, “It was a period where there were personal changes in my life, and after casually visiting Noto, I knew I had to leave Catania.” Although the two towns are so close, they are worlds apart. “Catania is black, the lava-rock buildings blackened by the soot and ashes of the volcano. Noto is a golden-coloured sandstone, the light is different, it has a suspended metaphysical energy,” he says. Fiorentino was “reborn” in Noto as a painter.

Sergio Fiorentino in his home studio in Noto, Sicily.

Fiorentino’s paintings might be described as classically contemporary, with faces and figures realized in brisk blue brush strokes, a sudden beauty that is at once momentary and permanent. “What I am surrounded by here immediately entered into my repertoire,” he says. “The blue of the sky and the sea which I see every day envelopes the faces of my characters.” The ultramarine blue is a symbol of sacredness and rebirth. “What I do is isolate my characters in an amniotic dimension and then let them breathe inside the blue.” Approaching closer to each painting, the viewer perceives Fiorentino’s scratching technique, recalling what he describes as “the walls of the buildings with all the cracks and signs of the times.”

Fiorentino’s studio and living space in Noto exemplify Sicily’s mix of old and new, combining midcentury modern furniture and a minimalist vibe in a former Cistercian convent designed by Rosario Gagliardi in the early 1700s. Crediting his friend Giovannino with the discovery of the place, Fiorentino laments the condition he found it in before restoring it to its former glory: “an apartment block of 12 rooms with a false lowered ceiling, the stone floors and original plaster all covered.” He and Noto-based architect Massimo Carnemolla, founder of +Cstudio Architetti, conceived the current space.

Sergio Fiorentino’s studio and living space in Noto exemplify Sicily’s mix of old and new, combining midcentury modern furniture and a minimalist vibe in a former Cistercian convent designed by Rosario Gagliardi in the early 1700s.

There is a fluidity to the home studio. The living and working areas aren’t chopped up with barriers but defined by pieces from his furniture collection, a nod to Fiorentino’s former life as a gallerist in Catania: a Federico Munari sofa and lounge chair, a 1950s floor lamp by Giuseppe Ostuni for Oluce, Stilnovo wall sconces, and a 1950s Arredoluce lamp. Gio Ponti’s Superleggera and Vittorio Nobili’s Medea are part of a mashup of chairs around a glass-topped trestle table. In the main living area, blue threads with brass balls at the ends are suspended from the ceiling, pendulums that Fiorentino moves to relax and attract positive energy. But pride of place goes to his collection of over 100 Teste di Moro—the characteristic Sicilian ceramic vases depicting the face of a Moor—the oldest, from 1791, that he purchased at auction. (Fiorentino hopes to open a museum space in Noto one day, to display his collection.) “I have always collected, even in a pathological way,” he confesses. “Since I started painting, I have recovered somewhat. I need to surround myself with beauty daily. Now, I do so with my things, whereas before I did it with other people’s things.”

Fiorentino, who loves the ancient, creates for eternity. “Sicily has a great history in decorative arts, and today, in 2023, while I have a contemporary vision in art, there is a link with history,” he opines. “Blue is the colour of antiquity; lapis lazuli, the stone of the Madonna,” he says. “It is a colour with positive feelings and emotions and the very material of my characters.” His large-format Face Series paintings recall classical beauty filtered through his own dreamlike vision. The faces are “sometimes real people, and other times imagined,” he says. “The only paintings I have never sold are of my daughter, Alice,” who at nine years old already has a personal collection.

“My painter’s palette is deliberately poor,” he states. It basically has four colours: “White for light, a brown for shadows, and two opposing hues: blue, which is the soul, the spirit, and red, which represents the flesh.” (At times, he also uses gold, but he notes, “gold is not a colour.”) He works in oil and acrylic paint, his signature “scratches” creating a texture of blue threads that “protects them from the world.” Of his technique, he says, “I paint with the flesh tone, the skin in oil, and when the oil is still fresh, I scratch it so you see this texture of threads.” The result is a sort of filter between the observer and the portrayed face—a feeling of silent immobility characterizes the canvas.

_________

“Sicily has a great history in the decorative arts, and while I have a contemporary vision in art, there is a link with history. Blue is the colour of antiquity; lapis lazuli, the stone of the Madonna. It is a colour with positive feelings and emotions and the very material of my characters.” —Sergio Fiorentino

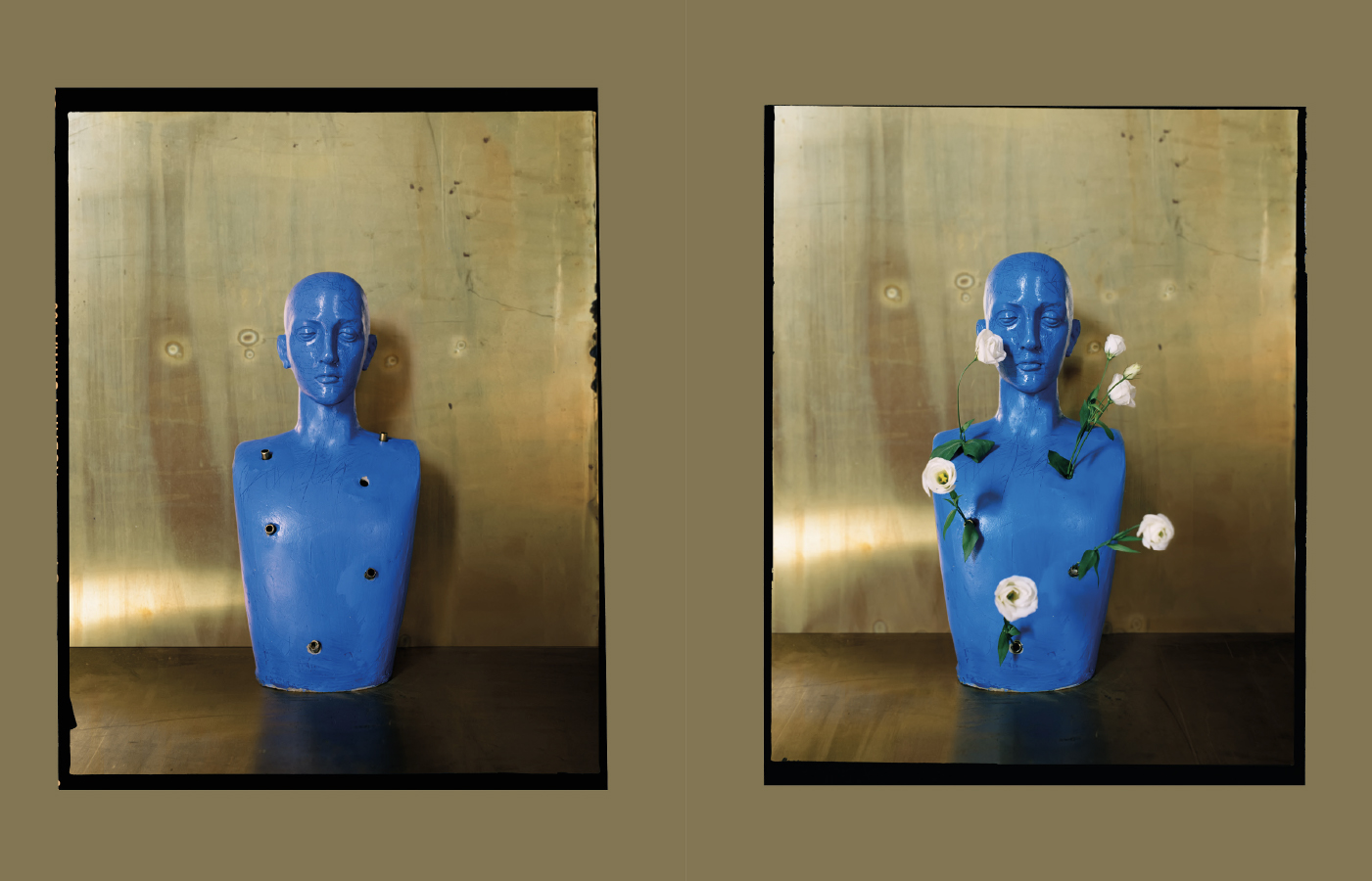

In addition to painting, Fiorentino also creates limited-edition sculptural furniture in materials such as brass, bronze, and silver. Presented at Fuorisalone earlier this year, under the porticoes of the cloister of the University of Milan, the Studio Nomade d’Artista installation displayed various objects: Mobile delle Aguglie, a sideboard with bronze fish pulls that double as mechanisms that slide left and right to reveal secret drawers; Vaso di San Sebastiano, a majolica ceramic bust with holes in its chest that house brass inserts that act as mono-flower vases depicting a flowering saint; Frammento, bronze heads that open by pressing the lapis lazuli eyes to reveal the Sergio Fiorentino signature blue. “Every piece hides a secret to access in which you need to find the key,” Fiorentino says.

To date, Fiorentino has seen his new artistic passion as more hobby than work. “From the day I decided to change my life leaving Catania, I knew it was important to give myself a daily cadence, to paint every day and have a rhythm but at the same time to have the freedom to create what I want,” he says. “My fear is that if I commit myself to any one gallery, I will have to become project focused, and my art will no longer be a passion.” Although Fiorentino does view his craft as a job, “it is a job of freedom.” In the three-month lead-up to his Milan debut, Fiorentino worked “from morning to night,” and his studio, for the first time, felt more like a factory than freedom. As an artist whose trajectory is on overdrive, this balancing act is one Fiorentino knows he will have to figure out.

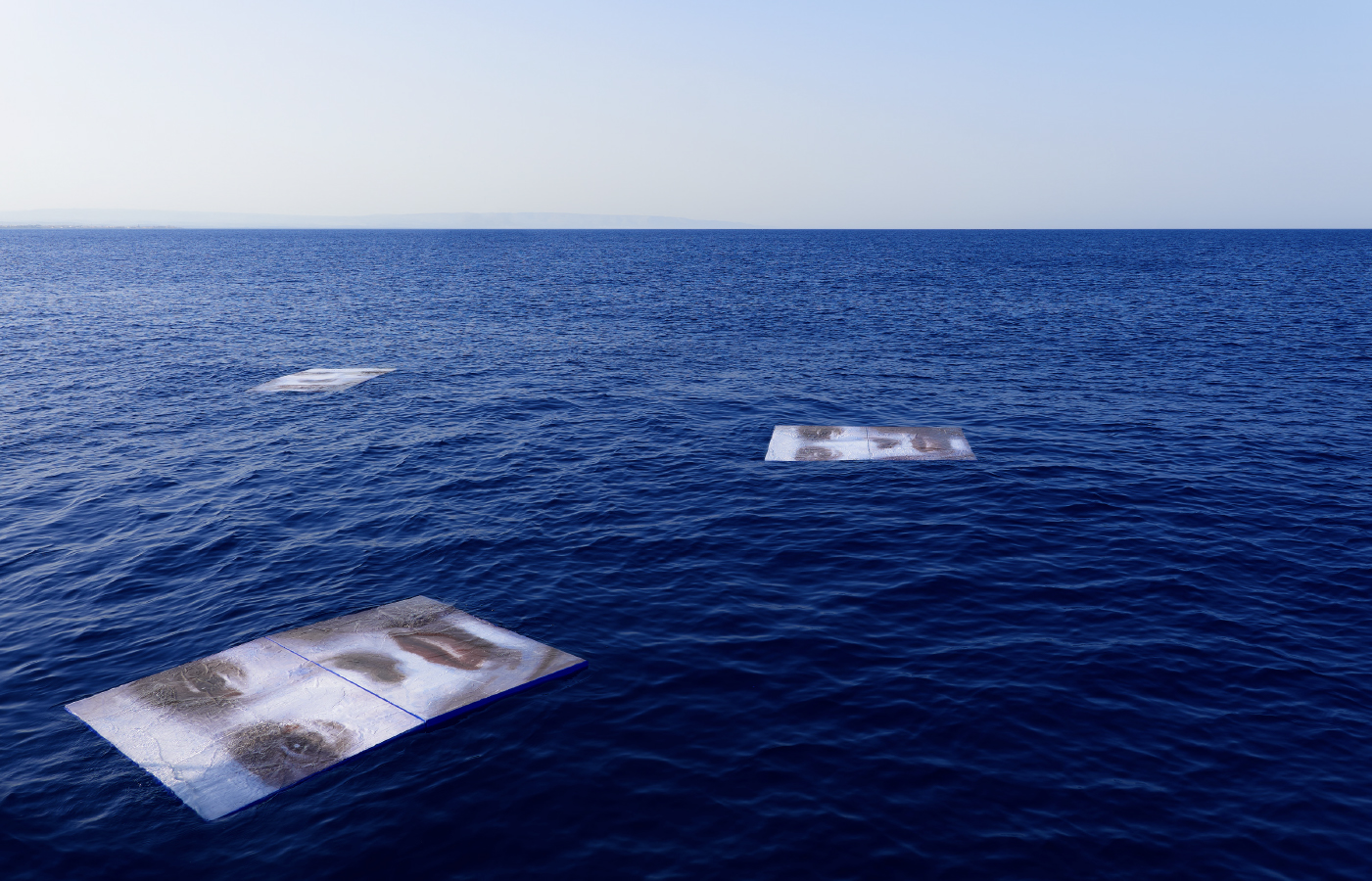

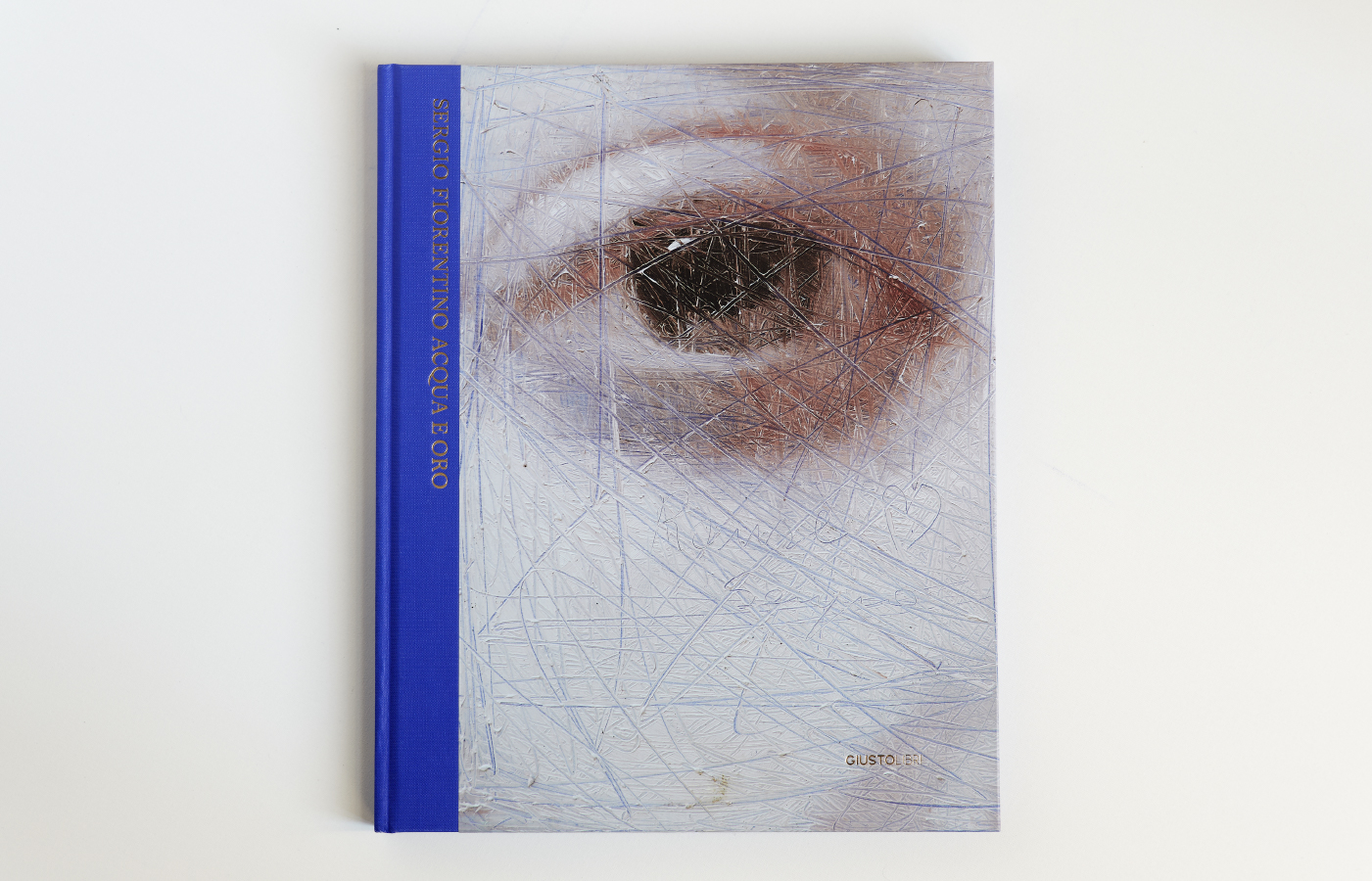

There is an aura of mystique to Fiorentino: his deep-set eyes and raspy smoker’s voice have a past that he communicates through his art. In his new book Acqua e Oro, with splendid images and creative direction by photographer and life partner Rosita Gia, and published by Miami’s Giusto Libri, he explains: “I try to imagine my characters out of time, out of a place, sometimes without gender. Figures that are so human but that come from another planet. All very different one from the other, these are beings who, breathing in water, glowing with gold, slowly become all similar to each other, as if they were part of one big family. Faces, eyes closed or open, are born protected by water.”

_________

Sergio Fiorentino sees his artistic passion as more hobby than work.

Acqua e Oro, Sergio’s Fiorentino’s new book, with creative direction by Rosita Gia, and published by Miami’s Giusto Libri.

Vaso di San Sebastiano, a majolica ceramic bust with holes in its chest that house brass inserts that act as mono-flower vases depicting a flowering saint.

The coffee-table tome is divided into two sections: “Water,” which includes a series of photographs of Fiorentino’s large canvases of faces floating on the sea, and “Gold,” in which his canvases of contemporary saints are photographed against stone quarry walls 50 metres high as if to convey an idea of ascension into the heavens. “The works are immersed in nature as in a desire to return to the elements that inspired their

creation,” the artist says.

Fiorentino notes that Noto’s otherness “naturally selects very interesting creative personalities.” Notable architects, designers, musicians, and artists now call Noto home. “On the one hand, it is beautiful,” he says, “but it certainly becomes a place in danger of losing its authenticity. So far it hasn’t happened,” he affirms. “Noto still retains its small-town charm with a burgeoning colony of creatives that stimulate the creation of beauty in an autonomous way.”

The vibe of slow living permeates Fiorentino’s home, where there is a mandate of no television and no Wi-Fi. “I try to live in a more personal dimension, distant from the sprinting of everything that is happening around us,” he says. “Every day is filled with so many beautiful things that I don’t need television. I like the movies. I like to go to the cinema, but there is no cinema in Noto, and so I have to go to Rosolini or Avola. But I like this too, as not everything is so close at hand, and thus it makes going to see a movie desired. Even going to a neighbouring town gives me more time to understand that I am choosing to do something beautiful. I prefer to live like this.”

At times Fiorentino speaks in fragments of poetry on beauty, articulating the workings of his creative mind, as in his book: “I remember the childhood boat trips with my family, the love of the sea that was passed on to me by my father, and that feeling of being in suspension and in flight beyond the force of gravity. Everything would become lightweight, and that blue enveloped me. It was a full-bodied, intense, almost solid, sacred blue. Today, that very same blue envelops and protects the figures on the canvases.”

In doing so, Fiorentino transforms the anonymity of Noto blue into celebrated works of art.