Scalawags: Edward James

The eccentric English dilettante.

It was early one morning, on the terrace of Hotel San Ignacio in Xilitla, Mexico, and I asked the manager where the structures were. He pointed toward distant mountains. “That way,” he said, shaking his head as if in wonderment at something he couldn’t understand.

“What about the man who built them?”

He shook his head again with the same expression.

I set out on a five-kilometre walk down a dirt road bordered by wild impatiens and marigolds, the air scented by gardenias. Rounding a bend, I saw, twisting and poking their way up through the thick forest canopy, 20 cement treetops, and a couple of strides later I got a look at giant snakes, gates, clamshells, towers, and stairways to the stars.

This all came back to me the other evening as I watched an old movie, a weird psychosexual western from 1946 called Duel in the Sun, with a scene, early on, of a woman dancing on top of the bar in a saloon. She’s all sensual fire, dark legs revealed through rustling skirts as she stomps her high-heeled shoes and tosses her thick black hair. Her real name was Tilly Losch, Austrian star of European ballet and musicals, and she was, for a few years, the wife of Edward James.

Edward was born in England in 1907 to parents who had both inherited huge fortunes. His father, William James, died when Edward was four. His domineering mother seemed dedicated to only two things in life: miserliness and criticizing her son. Their houses were always filled with kings and dukes. It was rumoured that after the birth of his four sisters, Edward’s father had become impotent, and that King Edward VII was his real father. Edward James always denied this, insisting that Edward VII was only his grandfather.

He was sent off to Eton at 13, and after a few years, he convinced his mother to let him go to school in Switzerland. There he displayed habits that would be noted throughout his life. He was always late, always forgetful, and always dreaming. Of Edward at 18, a tutor wrote, “He is so childish for his years and requires the same kind of handling as a small boy.”

At Oxford, other boys made fun of his dreaminess and childlike nature. He spent his time writing poetry, taking flying lessons, and sending off 20-page letters to his mother and the servants. After graduation, he went to New York to stay with a half-cousin, Arthur Curtis, one of the wealthiest men in America. While there, Edward and a girlfriend stole a sandhill crane from the Bronx Zoo. The theft made the papers. It was a mystery: How did culprits snatch a bird that size, and where was it? Fortunately or unfortunately, cousin Arthur was on the zoo board. The crane was returned just as mysteriously as it had disappeared, but Edward was sent packing.

Back in Europe, Edward somehow got himself appointed honorary attaché to the British embassy in Rome. He spent most of his time ignoring his duties and entertaining lavishly. His job was the deciphering of cables, but he was in the habit of writing questionable letters on embassy stationery to strangers, one of them being Mussolini. Edward made a mistake with a cable, stating that Italy was building 900,000 submarines, and for a couple of days Great Britain was on a war footing. When it was learned that the actual number was nine, Edward was fired. He’d later say, “It’s the only job I ever had.”

In 1930, he saw Tilly Losch onstage, and it was love and lust at first sight. He besieged her with gifts and poetry, and they were soon married. One day, he watched as Tilly emerged from the shower and walked, dripping wet, up the stairs. He was entranced by her footprints on the wood of the stairways. He got casts made and had Tilly’s footprints woven into a stairwell carpet.

Edward James devoted himself to being a patron of the arts, commissioning works from numerous singers, dancers, and painters. He was René Magritte’s first patron and for many years Salvador Dalí’s main patron.

Edward and Tilly fought continually, and their divorce was appropriately stormy. He sued, claiming she was having an affair with Prince Serge Obolensky. She countersued, claiming he was a homosexual, basing her suit on the fact that she heard some Italian tenor singing with happiness in their home. In court, the tenor produced his passport to show that he was in Argentina at the time of the happy singing. Edward had been playing records. Although Edward would soon fall in love again, with actress and model Ruth Ford, men would otherwise dominate his romantic life.

He devoted himself to being a patron of the arts, commissioning works from numerous singers, dancers, and painters. He was René Magritte’s first patron and for many years Salvador Dalí’s main patron. In 1937, Magritte produced The Pleasure Principle (Portrait of Edward James) and his most famous painting, Not to Be Reproduced, for which Edward modelled. It shows a man looking in a mirror, but the image in the mirror is the back of the man, not his face. He collaborated with Dalí on the famous Dream of Venus pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. In addition, Edward hired Dalí to help transform his cottage in England, called Monkton House. This home became the site of the notorious sofa in the form of Mae West’s lips (the concept was Edward’s) and also housed the Lobster Telephone.

Edward eventually broke off relations with Dalí, repulsed at his greed and avarice, but the final rupture occurred when Dalí lent his support to General Franco, who would overthrow the democratic government of Spain and install a military dictatorship. The loyalists had one bomber plane; it had been given to them by Edward James.

When he wasn’t handing out money, buying paintings, or collaborating with artists, he was making friends and fighting with them, buying houses and animals, and travelling almost incessantly. Like the little child that he had been and was still in many ways, Edward would lose track of where he put his toys—be they houses, boa constrictors, books, or paintings. He was forever showing up at the airport without his passport. Once, intending to fly to Scotland, he wound up in Iceland. He liked the country so much, he kept returning.

His activities are impossible to trace—he once wrote a letter to a friend, apologizing for not meeting him in Paris as planned because Ruth Ford had refused his third marriage proposal, so he’d gone to Romania to see a shepherd who had met Christ.

Edward bought and sold houses all over the world. Nevertheless, he would stay in hotels. At one point he was banned from the five best hotels in Los Angeles. One hotel manager refused him a room, saying, “The plumber’s bill will be more than the room rent.” (Edward was obsessive when it came to washing himself.)

He employed secretaries at each of his owned or rented domiciles. Some would last for years, others minutes. One of the former was a Miss Prufrock, who was frequently seen beside Edward in the front seat of his Rolls-Royce or his Duesenberg, taking dictation. One of the latter was Lauren Bacall’s mother. And the American poet Mary Barnard lasted two weeks. “I got the job,” she said, “because I could spell Tchelitchew and Klee.” She showed up for work one day at his hotel room in New York only to find that he had gone, leaving behind “three shoes, four of his artworks on the wall and suspenders on the couch.”

Most of the artists he knew played at surrealism; they either posed as surrealists, as did Dalí, or led conservative lives, as did Magritte, while turning out surrealist works of art. Edward lived a surreal life, and he had been doing so for decades when, in 1947, he found Xilitla.

Edward was travelling around Mexico with a handsome young man he had met in Cuernavaca named Plutarco Gastélum Esquer. They were in the mountainous regions of San Luis Potosí when they came across a waterfall in the jungle. When I visited decades later, Plutarco’s son, Plutarcito, said to me, “My father and Mr. James went for a swim in the pool at the foot of the waterfall. After a couple of minutes, Mr. James realized their chests and shoulders were covered by butterflies. And he said to my father, ‘This is it.’”

Edward immediately bought the land around the waterfall and had the idea to raise orchids and provide a refuge for animals. But one morning, staring out over his property, he had a vision in which he saw the riotous vegetation that surrounded him duplicated in a mirror-image jungle made from cement. It was like a vegetal dream that mirrored his own complex subconscious, and he set to work, drawing up plans and hiring dozens of local people to help bring his dream to fruition. The work went on for years. In the meantime, Plutarco got married and built his home, Posada El Castillo, where Edward also resided when not at his jungle paradise, which he called Las Pozas (“the Pools”). Edward died in San Remo, Italy, in 1984.

Edward James attracted detractors and sycophants all of his life; many of these were the same people. They liked to portray him as a failed artist with a big pocketbook. Even Las Pozas, it has been said, was the work of Plutarco, not Edward. In a cottage near the site, I discovered two trunks filled with sketches and drawings by Edward James. The people who had possession of these trunks had taken care of Las Pozas after it had fallen into neglect. There were dozens of these drawings, and they served as working plans for the monuments and sculptures at the site.

One other thing: Edward had misshapen feet (as a result of his mother insisting he wear the same shoes for years when he was a boy). It has been documented that Edward cast his weirdly shaped feet in cement and from these made a footpath to El Castillo. Edward James would get a laugh knowing that all over the world people are literally following in his misshapen path.

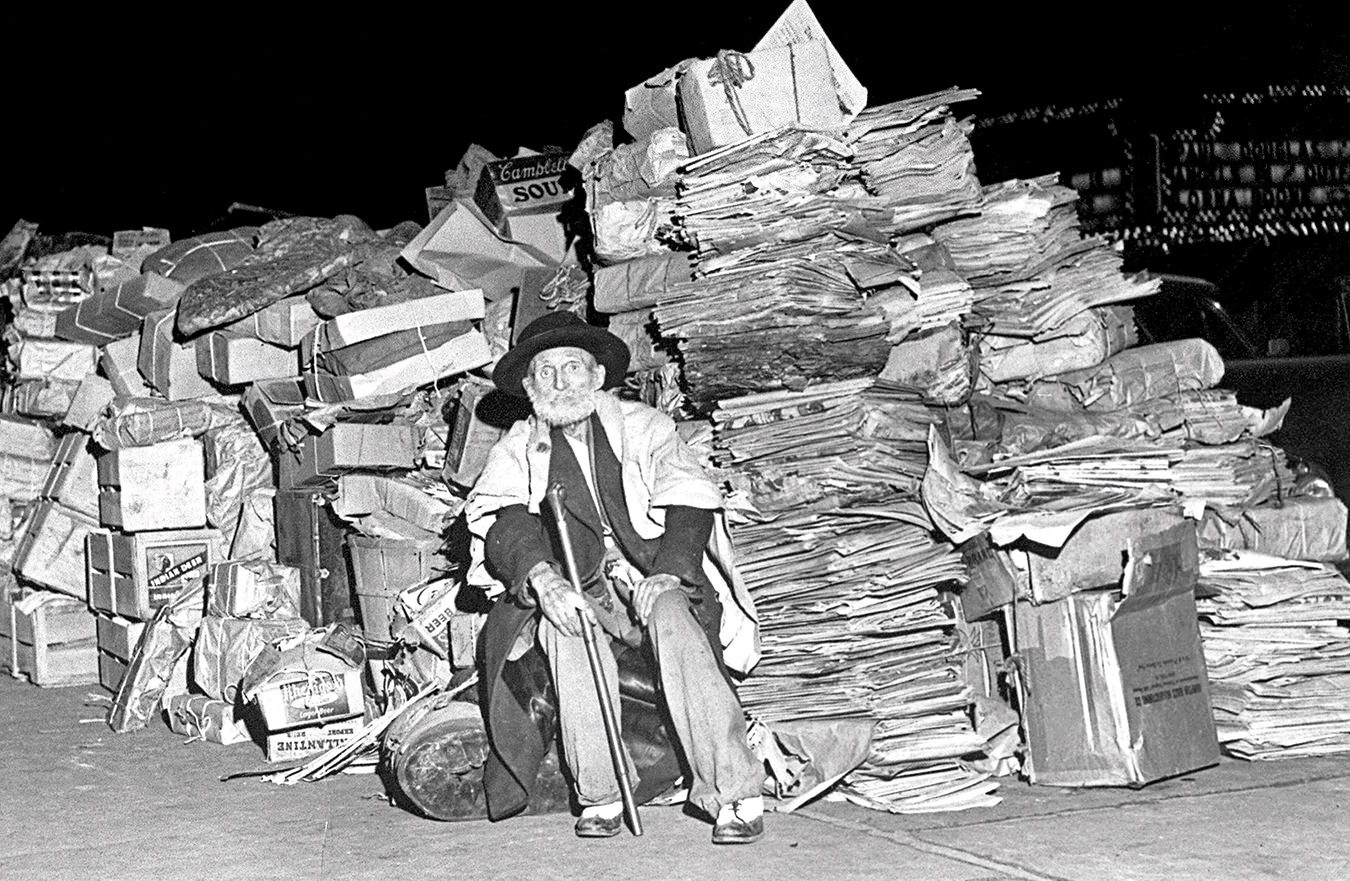

Photo provided by the Edward James Foundation.