(Not So) Great White North

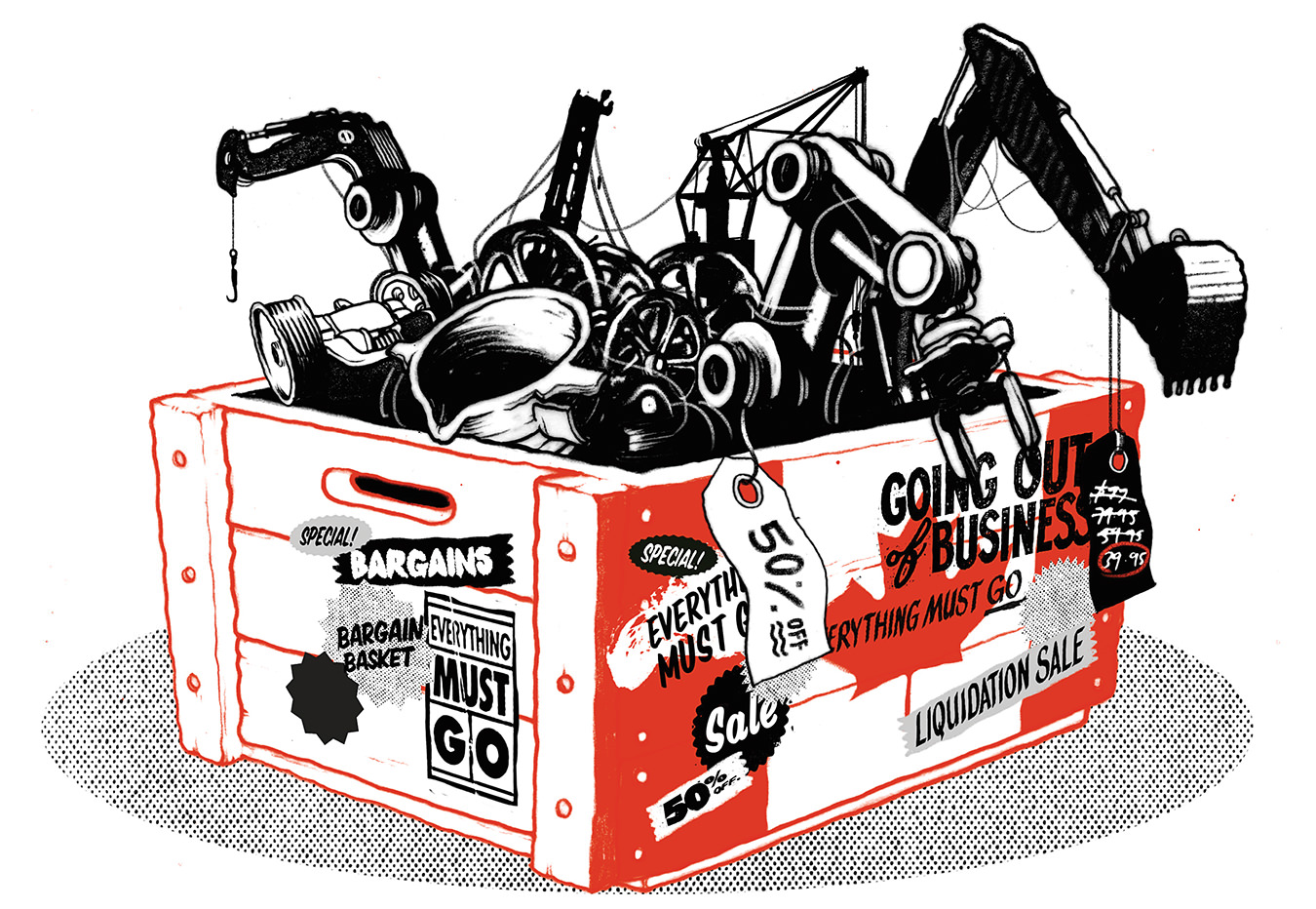

Hard times in the Canadian equities market.

Ahhh, those were the days. In 2008, the world economy was swooning. Stock markets on all five continents were in freefall. The titans of Wall Street were drowning in an ocean of red ink—as were several European countries. There, amidst the financial apocalypse stood Canada, so long the punchline of world’s capital markets, bruised and battered, but still standing: the True North strong, free, and best of all, profitable.

Over the next several years, while our American cousins struggled to make their mortgage payments and our European friends struggled to keep the disaffected from smashing every window on the continent, Canadians reaped the rewards of an economy based largely on hewing wood and drawing water. Our miners crushed rocks and smelted ore. Our farmers sowed seeds and gathered harvests. Our refiners drilled and fracked and pumped as much as they could within the confines of a 24-hour day. Even our bankers, long cursed and vilified by their customers at home, were praised and celebrated by the financial illuminati for their buttoned-down, stick-to-their-knitting business model. And all was good.

That is, until it wasn’t. After several years of strong performance, clouds have gathered over our economy. GDP growth has stagnated and job growth seems stuck in neutral. As of June of this year, Canada is now the worst-performing market in the G7 group of economic powerhouses. A distinction doubly ignominious considering that group includes perennial economic basket case Japan, as well as Italy, the current sick man of Europe.

The hard times have come to Bay Street too. Consider the facts: for the first half of this year, the S&P/TSX has suffered a 0.88 per cent loss. By no means a disaster, but considering the broadly based S&P 500 index south of the border has posted an impressive 13.8 per cent return over the same period (20.3 per cent if you care to factor in the 5 per cent decline in the loonie versus its U.S. counterpart), it’s certainly cause for concern.

Some economists and analysts have characterized such under-performance as nothing more than reversion to the mean—call it the “what goes up must come down” theory of investing. Others believe it is a sign of something more foreboding: that the raw materials, energy, and other resources that have served our economy so well as commodities over the past decade are no longer in vogue.

Which leaves Canadian investors with some difficult questions. Has our time (or at least, that of our stock market) come and gone? Is the current round of underperformance a sign of things to come? Or is it merely a pothole on the road to prosperity? Should investors view this underperformance as an opportunity to load up on all things Canadian? Or the warning sign that something is not quite right up here in the Great White North?

Digging In; Pulling Back

Rarely do the wild mood swings of the Canadian market cause Vijay Viswanathan stress and alarm. On the contrary: as the director of research at Mawer Investment Management and co-manager of the firm’s award-winning Canadian Equity Fund, Viswanathan is paid to keep his cool while others are running for the exits.

So it is this time around. As Viswanathan explains, the recent underperformance of the Canadian equity market is less an example of cruel and fickle fate than it is a case study in supply and demand. Or to put it another way, it’s tough to make a buck when the world is buying less of what you’re selling—in our case, base metals, gold, potash, oil, and gas.

“Those have been pretty big tailwinds over the last decade plus,” Viswanathan reflects. “There’s been a pretty significant commodity supercycle over the past 10 to 15 years. I think what we may be seeing is that the secular bull market in commodities [may] be coming to an end. What’s happening is that supply is catching up to demand, [and] demand growth is slowing.”

As Viswanathan explains, this supercycle has had a supersized impact on Canada because of the composition of the Canadian equity market. With energy making up about 25 per cent of the TSX composite, and materials another 19 per cent, as the price of commodities rise, so too will share prices. Conversely, a pullback in either of these two sectors (much less both at the same time) is inevitably going to show up on the portfolio statement.

“The [Canadian equity] universe is not that wide,” Viswanathan says. “So if there are certain sectors or certain industries that are suffering from downturns in the market, that’s going to have a pretty material effect on the overall return of the market. Then there’s the knock-on effects on the rest of the economy that has derivative exposure to commodities—if there is a pullback, that’s going to impact a lot of things.”

And what (or who) is behind the commodity pullback? Blame China—as well as the India, Brazil, Mexico, and an entire gaggle of other emerging market economies. “A big part of investing in Canada—I think sometimes Canadian investors, they don’t have a complete handle on [this]—investing in a lot of Canadian companies is really a derivative bet on China [and] emerging markets growth,” Viswanathan says.

Infrastructure, in other words: the roads, airports, and office towers that fuel the economy. “As China and other emerging markets slow down their rapid infrastructure spending … that demand for commodities is shifting to more consumer-led economic growth,” he says. “[That] could be [a] risk for commodity players, because that demand growth is not there.”

Not to say that the outlook couldn’t change. “There are lots of different scenarios that could play out,” Viswanathan admits. “[Maybe] there is suddenly significantly more automobiles purchased by the Chinese. Or demand for oil. [Or] more demand for fixed-asset investment in other parts of the world.”

That said, Viswanathan isn’t holding his breath. “Where does that demand growth come from, that’s the question. Could the U.S. make up for that? Maybe. Our base case is that, well, probably not enough.”

The Search For Value

Viswanathan believes the time has come for those looking to put their money to work in the Canadian market to face an ugly truth: from an investment perspective, there isn’t a lot of “great” left in the Great White North.

“It is not easy in Canada right now,” says Viswanathan. “Our take is that valuations within Canada are fair. There are not really that many bargains out there—I think that’s important [to recognize].”

Viswanathan is cautious about sifting through the bargain bin for beaten-up Canadian commodity producers. He thinks there are good reasons why the market has taken a stick to share prices in the materials and energy sectors this year—and that goes double for the gold miners. “We never say never,” he muses. “[But] we’ve done work on Canadian gold producers and we’re just not there on the business model—we just don’t think it’s a wealth-creating business model. Then from a valuation standpoint, based on our discounted cash flow models, our thoughts are that the gold price assumption for the next hundred years is not at acceptable levels for us to take that risk.”

Given such comments, it’s not surprising that Viswanathan remains significantly underweight in the stuff that has caused all the mess: at last count, the entire materials sector makes up a meagre 2 per cent of the Mawer Canadian Equity Fund.

As for some of the more traditional safe havens of the Canadian investment scene—pipelines, consumer products, utilities—Viswanathan isn’t exactly head over heels. The reason: valuation. “We would make the argument that some companies that could be classified as your high-quality, safe-haven companies within Canada are starting to get closer to the more expensive range,” he says. And telecom? “At this point, the best characterization is that we’re neutral,” he says. Viswanathan notes that increased competition and regulatory uncertainty are casting shadows on the industry.

So that leaves what, exactly? Viswanathan acknowledges the difficulty of the question. “Where do you go, right?” he asks rhetorically. “That’s the tough part. If you don’t necessarily want to have your energy exposure, or you don’t want materials exposure, [then] where?”

Well, financials, for one. In particular, the Canadian banks. “Within the Canadian large-cap universe, it’s probably the best risk-adjusted return potential,” Viswanathan says. “[They] are very well-run, well capitalized, and valuations seem reasonable for the returns investors should be able to get. Plus, you’re getting 4-per-cent-dividend yield in some cases, which is not bad considering if you take a look at where the 10-year bonds are.”

Within the space, Viswanathan has some clear favourites: “TD, Royal [RBC], and Bank of Nova Scotia [Scotiabank] would be three,” he says. “Could there be some headline risk or some issues if we have a downturn in the Canadian housing market? Well, yeah. But I think … if someone made that investment today, if they looked at it in 2023, I think they’d be happy with that investment.”

Beyond the banks, Viswanathan also likes the Canadian life insurers—Manulife Financial and Industrial Alliance in particular. “They’ve done a very good job over the last few years of de-risking,” he points out. “There’s less and less—if any—talk about exposure to interest rates, or exposure to equity markets. They’ve changed pricing. They’ve gotten rid of products that didn’t make sense.”

Perhaps most importantly, when interest rates take a turn, life insurers are one of the industries that will profit from rising rates. “Over the long term, that should be a tailwind for them.”