Scalawags: Honoré Jaxon

The rebel William Henry Jackson.

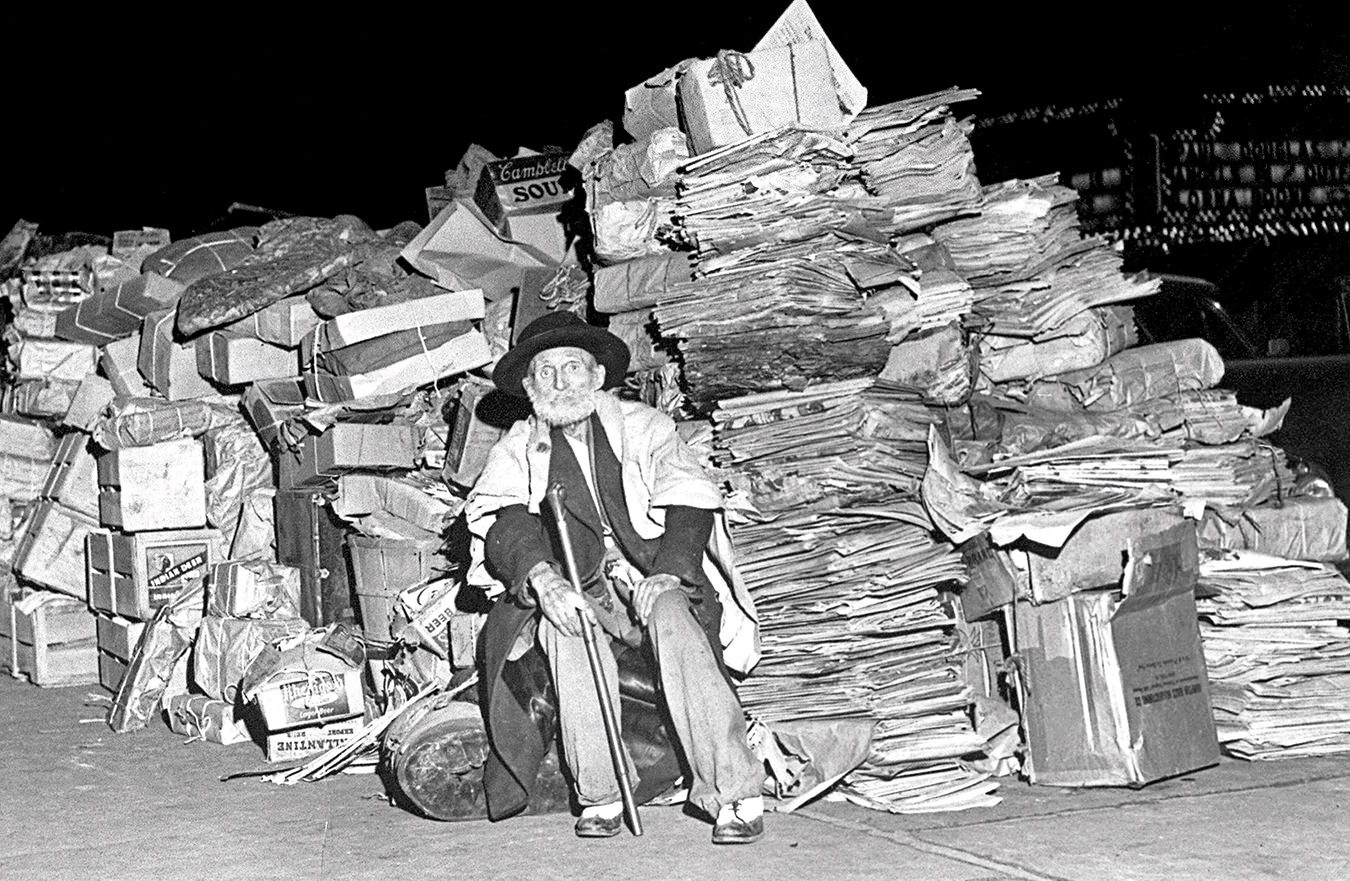

Honoré Jaxon, surrounded by stacks of books and magazines, on the streets of Manhattan on December 12, 1951. Photo by Hal Mathewson/New York Daily News archive via Getty Images.

Had you been strolling down 34th Street in Manhattan back on December 12, 1951, maybe a tourist headed for the Empire State Building just down the way, you would have come upon a most curious sight: a massive collection of books and papers commandeering the sidewalk for 11 metres, stacked two metres high and three metres deep. Perched on this mountain of bundles and crates was a little 90-year-old man with a white beard, threadbare black suit, black cowboy hat, and wingtip shoes. Passersby heard him speaking, in an incongruous loud, booming voice, about injustice: done to him, to the Indians, and to the workers of the world.

The cop on the beat was heard to remark, “Hey, this is New York. We’re used to characters, but this one…”

The old fellow sat out there all day and slept there all night. He had nowhere else to go and he had to protect his “archive”. The next morning, when he awoke in a cave dug between stacks of papers, he was the talk of the town. The old man was described by an acquaintance to a New York Times reporter as “Major Henri Jaxon, son of an Indian maiden and an adventurous Virginian … born in the sweet grass hills of Montana … and once tried for treason by the Canadian government.”

Well, that’s who and what he was in his heart and in his mind, since over the last decade or so of his life his mind had been allowed to roam completely free over imaginary prairies and plains. Of course, it had been unfettered—his mind—for a lot longer than that. The treason part, however, was true.

When he was born, on May 13, 1861, the name on his birth certificate was William Henry Jackson, but to point this out seems, in light of his incredible journey through life, somehow another injustice.

He first saw the light of day in Toronto, where he was born to strict Methodist parents, recently arrived from England. He was inadvertently saved from a life of dour righteousness by a father who was interested in politics and was a failure in business. When his son was nine years old, the father read him a circular about a “half-breed” out in the Territories who was stirring up trouble, a man named Louis Riel. The boy had a contrary opinion to that expressed; he was sympathetic to Riel and his followers. The father took Jaxon to a political meeting when he was 11. His mother wrote to her sister in England that the boy returned that evening “greatly excited”. Right there are the main themes of his life: the Métis, injustice, politics, and being “greatly excited”.

When the rest of the family moved west, Jaxon stayed behind to study classics at the University of Toronto. He did well in school, becoming fluent in Greek and Latin, but he withdrew a couple of days before obtaining his degree. In 1882, Jaxon, too, travelled west to join his family in Saskatchewan. The last train stop was Qu’Appelle, 480 kilometres from his folks in Prince Albert. But that didn’t bother the boy; he walked the rest of the way. Jaxon turned his hand to various jobs, all without success. And then, in 1884, when word spread that Riel was returning from exile, Jaxon was there to meet him. The two men became fast friends and soon Jaxon was Riel’s secretary. In his journal, Riel asked Jesus to “take care of them always, if You please: my friend William Henry Jackson, whom I have chosen as a special friend, and all his well-meaning followers.”

According to intelligence reports of the North West Mounted Police (NWMP), “Jaxon seems to be a right hand man of Riel … I believe he does more harm than any Breed among them.” When fighting broke out, Jaxon was arrested by the NWMP and shipped to Regina. He was charged with “treason-felony”; the “felony” meant that if found guilty, he would not be executed. Jaxon wanted a trial so he could speak about injustice to the Métis, the Indian, and the settler. He was denied this right because his case had already been decided in private by the Crown, the defence attorney, and his family. He was to be declared insane and sent to an asylum. The hearing took little more than an hour. He was loaded in a wagon and transported to a lunatic asylum near Winnipeg.

At one point in his life, Jaxon was Louis Riel’s secretary. In his journal, Riel asked Jesus to “take care of them always, if You please: my friend William Henry Jackson, whom I have chosen as a special friend, and all his well-meaning followers.”

He was there only six weeks before escaping. Others had gotten away from the asylum, but all were captured; Jaxon was the first to avoid apprehension. Five days later, he crossed the border into Minnesota. After Riel was executed, Jaxon began hitting the lecture circuit through the Midwest. After a speech in Chicago, organized by anarchists, a newspaper described Jaxon as having a “dark complexion and high cheek bones [that] would indicate his origin [a Métis] even to a stranger.” Soon he was famous as an anarchist speaker. The Chicago Tribune stated that “among the ignorant class he gathered about him, he has become little less than a demi-god.”

By 1890, he was living in a room done up to resemble a Métis hunter’s shack, calling himself Honoré Jaxon, and so he would remain, except for the honorific of Major, which he bestowed upon himself a decade later.

He was loved by workers and bohemians, by anarchists, and by slumming society figures. When the Chicago Times called him “Indian for revenue”, he decided to take revenge. He organized the World Conference of Anarchists, and to host the event, rented a room in the Times building, next door to the publisher’s office.

Next Jaxon joined Coxey’s Army, that great group of men and women that marched to Washington to promote public works projects for the unemployed. Jaxon, dressed in Métis clothing, carrying a blanket and a hatchet, led the Chicago contingent.

Then he joined the Baha’i faith and fell in love with Aimée Montfort, whom he married in 1898. He even made an attempt at being conventional, which to him meant designing a tunnelling machine and patenting a device to protect buildings during earthquakes. Soon it became clear that even a conservative Jaxon was too much for his wife, who had the audacity to insist they spend money on running water and electric light. The two decided to live separately. A reporter for The Saturday Evening Post caught up with Jaxon in 1907 and wrote, “He looks like an Indian, talks like a graduate of Oxford and writes like a professor of rhetoric and he lives in two cluttered rooms at the back of a pickle factory.”

Jaxon ran for office as the federal representative for Prince Albert, and when he lost, he went to England on a speaking tour. More years were spent speaking throughout the United States and Canada, and he got involved with helping anarchist revolutionaries in Mexico. After arriving in New York to give a speech in 1919, he decided to stay.

When Aimée received some money from her family, she sent some of it to her husband, who bought a few properties in the Bronx. On one of these in 1923, Jaxon started to erect what he called his “fort”. His building material consisted of 700 large ammunition cases obtained (legally) from the U.S. Army. This edifice, eight metres high—not counting the tall, tin cupola—became famous as the Box Castle Garden.

In 1927, a fire destroyed his castle and many of his books and papers; he claimed the mobster Dutch Schultz was behind it. Jaxon moved to another property and started building another place; he referred to this as Camp Contentment and himself as Buffalo Heart. Desperately poor by now, he acceded to his wife’s wishes to sell one or more of his properties, but no sooner did he put the places on the market than the Depression hit. The city stepped in to expropriate his land, but Jaxon protested, saying they didn’t have the right to because he was an Indian and the Indians had never signed their land away. His old friend Frank Lloyd Wright visited him in 1936 and told reporters back in Chicago that Jaxon was “living in a big barn amid vast piles of newspapers, dreaming world reform while rats raced past him.”

In 1932, his wife died and the city demolished his latest fort. He was 80 years old and homeless, yet he could write to his sister, “I am now free for new and joyous adventures.”

His associates in his last decade included the Chanlers, a patrician New York family, and a Nazi sympathizer named Kurt Mertig. Jaxon had fallen in with the latter because Mertig, as an organizer of pro-Nazi forces, protested the treatment of Native peoples by the American government. The Chanlers and Mertig each provided the old man with at least one meal a week.

Despite his age, Jaxon worked three jobs, rising at five in the morning to stoke the furnace of his apartment building, running a newsstand on 84th Street, and collecting garbage from a building on 83rd Street. In the summer of 1951, he was run over by a car but let the driver move on because he knew it was not the man’s fault.

One day a friend called Wall Street Abe took him to the offices of the Bowery News, where he was roundly welcomed. It was the editor of the Bowery News, Harry Baronian, who rescued Jaxon from his perch atop the massive sprawl of papers, where he’d lived a few days on the streets after he was evicted from his apartment. Baronian, an ex-hobo, had a truck bring along 60 of Jaxon’s boxes. The rest were sold for scrap. At the paper’s offices, the Old Majah, as he became known, was washed and kept fed by an ex–snake charmer called Boxcar Betty. Additional assistance was supplied by Baronian and Bozo Clarke, a clown known as the crown prince of the hoboes.

But Henri Jaxon had undergone too much recent hardship—hit by a car, sleeping on the street, eating hardly anything. He suffered a serious relapse and was taken by his Bowery friends to Bellevue Hospital. On his deathbed, he told Baronian he had to get well in order to take all his papers and books back to Saskatchewan, to build a library for Native peoples. Jaxon died on January 10, 1952.

Photo by Hal Mathewson/New York Daily News archive via Getty Images.