Tod’s Shoes

A driving force.

On a fine Saturday afternoon in early April, sprezzatura is alive and well on Bloor Street West, Toronto’s boulevard of shopping dreams. It is no thanks to the street itself, which is a mess of construction as the thoroughfare is being gussied up with granite sidewalks.

Such self-declaring affectation is the very opposite of sprezzatura, an ideal of effortless style first delineated in Castiglione’s portrait of court life in Renaissance Italy, The Book of the Courtier, published in 1528.

This spring day, the smell of easy elegance wafts from the Harry Rosen store where a Tod’s artisan is demonstrating the making of the Gommino, a moccasin (also called a driving shoe) with a signature sole of rubber bumps that has made Tod’s a leading luxury brand synonymous with a certain kind of nonchalant elegance.

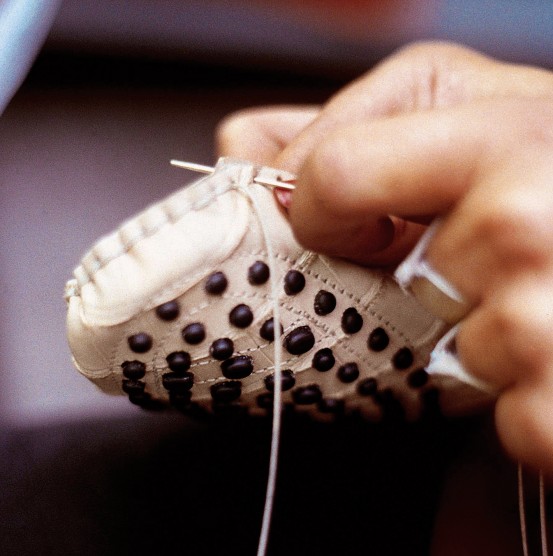

Of course, a shoe doesn’t get to be on the list of 50 shoes “that changed the world”—as London’s Design Museum has so declared the Gommino—without letting some effort show. Tod’s permits itself to flash a Made-in-Italy pride, and doesn’t mind letting it be known how much labour goes into hand punching the 133 holes in the leather through which the 133 rubber bumps protrude.

However, craftiness is not the work of cobblers alone. At the in-store presentation at Harry Rosen, the direct-from-Italy craftsman at his workbench is convincing. So too is the casual, circumspect, good-humoured manner of Marco Giacometti, chief executive officer at Tod’s North American headquarters in New York.

With the firm for 11 years, Giacometti, a native of Ancona (the shoemaking region of Italy where Tod’s began), is wearing tailored executive attire with penny loafers. These are Tod’s version of an American sportswear classic, but, instead of a penny, a coin also minted by Tod’s is slid inside the slotted vamp, suggesting a powerful realm with a currency of its own.

Artisans individually hand punch 133 holes into each leather sole, through which the rubber bumps protrude.

While he wears it well, Giacometti takes no credit for the “the craftsmanship, the chic, the quality” that are the core values of Tod’s. With courtly deference, he expounds the princely virtues of company chairman and CEO Diego Della Valle, whom he describes as “a visionary”.

Della Valle, one of Italy’s leading industrialists, took over his family’s shoe business in 1979 and turned it into a global brand christened J.P. Tod’s—and eventually just Tod’s—after an easily pronounceable name taken from an American phone book.

Today, along with Tod’s collections for men and women, there is a portfolio of labels that also includes the even more casual Hogan line and the even more exclusive Roger Vivier range.

Early on, Tod’s shoes were noticed after a pair was provided to Gianni Agnelli, the late head of Fiat who was also an icon of Italian style and most famous for his insouciant accessorizing, which included watches worn over shirt sleeves, neckties outside of sweaters. Currently, Julia Roberts wears Tod’s in the movie Eat Pray Love, based on the best-selling book.

Throughout the growth of the brand, its image has never strayed into the shocking or sensational. At the same time, its marketing has never been shy. For example, Giacometti—who says a lot in a few words—guilelessly admits, “We have product placement everywhere.” Indeed, in a few days Giacometti would be heading to Los Angeles for the reopening of Tod’s Beverly Hills boutique, where guests went from starlet Jessica Alba to stylist Rachel Zoe.

The California affair also reflected the subtler side of the Tod’s touch. The event served as a welcoming party for Jeffrey Deitch, new in town as the director of Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art. There was a new handbag by Milena Canonero, who has worked on films ranging from Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange to Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, and has been among Italy’s greatest contributions to costume design. On the third floor, there was the VIP showroom designed by Dante Ferretti, an Oscar-winning art director who has worked with immortals of Italian cinema Pier Paolo Pasolini and Federico Fellini.

Not all that effortless, perhaps, the Beverly Hills reopening was nonetheless a shindig with grace notes and was conceived with panache, which, in modern society, so entangled with the mechanics of celebrity and cash, may be as close to nonchalance as a global brand can get.