There’s Always This Year and Taylor Swift: Two Book Recommendations

Love letters to sport and a musician.

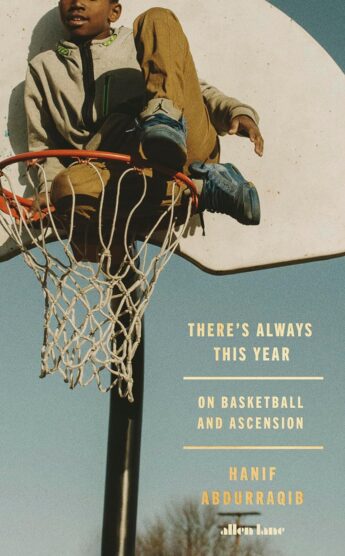

There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension by Hanif Abdurraqib

You might know Hanif Abdurraqib for his poetry, or perhaps for his 2017 bestselling essay collection, They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, named book of the year by over eight outlets, including BuzzFeed, NPR, and CBC. You might also know him for his beloved music criticism podcast, Object of Sound. Or you might know Hanif Abdurraqib, as some may have first encountered him, for a viral image of him presenting on Carly Rae Jepsen’s “Your Type.”

In There’s Always This Year, Abdurraqib turns his attention from the radio to the courts, chronicling the era of basketball he grew up alongside of in Columbus, Ohio. The book is equal parts sensitive personal memoir and Homeric ode to Ohio’s legends, both triumphant and defeated: LeBron James, Estaban Weaver, Kyrie Irving, among others. Throughout these historic highs and lows, Abdurraqib weaves meditations on precarity and fantasy, on homecomings and exits, on the metaphorical and material ways a sport can hold a neighbourhood together.

Because it is Abdurraqib, the text is romantic, guided by feeling over fanatical statistics. He finds intimacy as easily in enmity as comradery, and it’s his palpable adoration—for the game, for his friends, for his heroes, and for his home—that carries readers from page to page. Fans of basketball will, no doubt, revel in his nuanced and impassioned relationship to the sport, but those unfamiliar with layups and free throws will be just as compelled by his generous, genius cultural criticism.

Intimacy, Abdurraqib argues, is rooted in attention, and what a gift it is to be scrutinized by this poet-essayist, to be his subject. Innovative and illuminating, There’s Always This Year is a love letter in the fullest sense of the term.

Tavi Gevinson is no stranger to celebrity. Rocketing to stardom as an 11-year-old blogger, she went on to found Rookie Magazine, a formative internet magazine for teenage girls by teenage girls. Her cultural cachet has not diminished as an adult. Gevinson has performed on Broadway and on television, most recently in American Horror Story, and written eruditely for The New Yorker. Along the way, she also befriended one Taylor Alison Swift.

Billed as a “satirical fanzine,” Fan Fiction is a fictionalized account of Gevinson’s friendship with Swift. The 76-page zine is divided into three parts. The first act is a seemingly straightforward essay, a loving dissection of Swift’s songs framed by Gevinson’s experience attending Swift’s blockbuster Eras Tour. The second and third act complicate the first. In part two, “Gevinson” speaks directly and confessionally to the reader, divulging the inception of her fandom for Swift; how a series of generous, well-connected favours led to Zooey Deschanel introducing fans to a pop star; a summer visit; a New York sleepover.

The final act is epistolary: a series of emails and texts between “Tavi,” “Taylor,” and “Tree” (Swift’s publicist, Tree Paine). They are gripping, humorous, and heartbreaking. Gevinson is her most audacious in this finale, unafraid of letting her avatar’s composure unspool. It’s here, while “Tavi” and “Taylor” wrestle for ownership over the story of their friendship, that the text’s ambitious epigraph to Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire—a masterpiece of wild annotations and cannibalistic reverence—pays off.

As with a great Taylor Swift song, one can’t help but speculate where Fan Fiction adheres to and where it deviates from Gevinson’s real life. But Fan Fiction is more than its salacious subject. It is a finely crafted examination of the relationship between artist, fan, and art; the murky boundaries between relatability and projection; and how loving the work can sometimes, despite one’s best efforts, obscure loving the artist. It is a wicked and thoroughly modern romance—a delightful, kinetic read.