The Beautiful Untrue Afterlife of Oscar Wilde

Fan fiction for the ages.

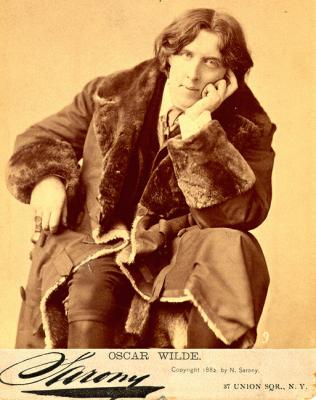

“Portrait of Oscar Wilde” by a forger c. 1920.

It’s a gloomy evening in 1920s London, and four people are huddled in a Chelsea parlour filled with candles. They are fixated on a woman who calls herself Travers Smith. On the table before her lies a Ouija board and a planchette. They are anxious to begin; they have questions, and they want to know the truth. Or, at least, a titillating version of events they can pass off as truth when retelling the story of the evening. This is a seance, after all—anything could happen.

Smith draws in a deep breath and calls forth her spirit guide, a 2,000-year-old Egyptian named Johannes: “Johannes. Will you summon Oscar Wilde?”

The greatest literary personality of the 19th century had died alone in booze-soaked poverty and exile two decades earlier, in 1900. But Wilde’s story did not end in that Parisian flophouse; it continued long after his death and became (if you will excuse the pun) even wilder. For the most part, not a word of what was said or written about Wilde after his death was true. However, the stories of the forgers of Wilde’s “afterlife” are extraordinary in themselves, and a new book, Beautiful Untrue Things: Forging Oscar Wilde’s Extraordinary Afterlife by University of British Columbia English Literature associate professor Gregory Mackie, shines a spotlight on the fan fiction and theatrics that shaped it.

Spiritualism originated in 19th-century America, rising and falling as fads tend to do. After the First World War, with so many people bereaved and desperate to communicate with dead relatives, spiritualism resurfaced. Certain mediums were very good at exploiting this desire, including members of a particularly serious and high-minded group called the Society for Psychical Research (which exists to this day and is extraordinarily well funded) that owned huge amounts of property in Chelsea, a place that was genteel yet bohemian. Travers Smith, born Hester Dowden, was a member of this spiritualist circle. She published a record of her supernatural communication with Wilde in 1924 entitled Psychic Messages from Oscar Wilde.

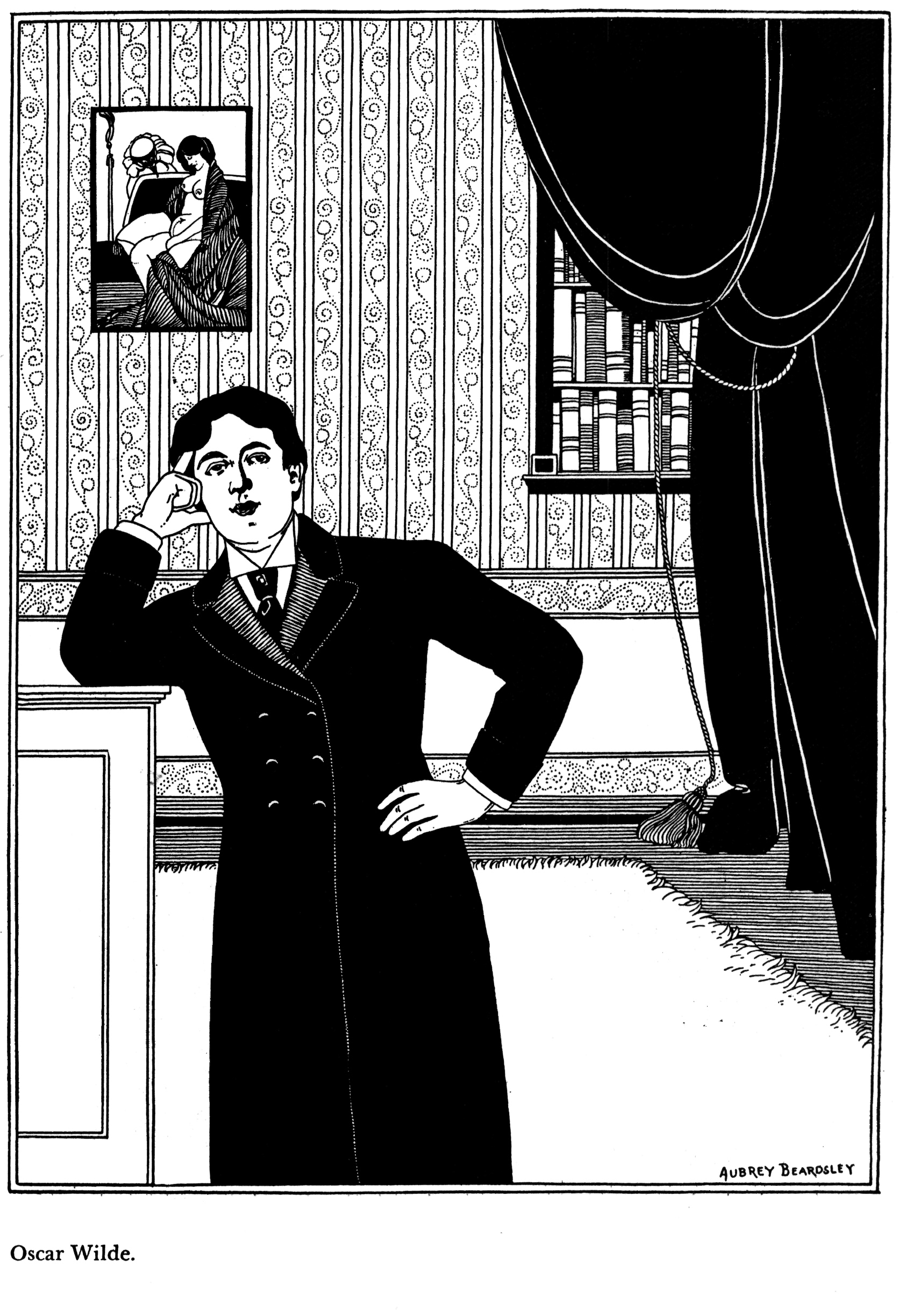

Handwriting facsimiles from Psychic Messages from Oscar Wilde, 1924.

“It’s completely batshit,” exclaims Mackie, laughing. “The level of seriousness with which these completely preposterous things are taken is both instructive and amusing.” There were different methods of communicating with the ghost world, he explains. “One was by Ouija board and one was by automatic writing. Ultimately, though, the ghost wrote a whole play that is pretty much unknown to scholarship because it’s terrible. [It was written] by Ouija board, so one letter at a time.” The play is called Is It a Forgery?

Of course, if you are speaking to the ghost of Oscar Wilde, he is going to have some witty things to say. Mackie gives the example, “Being dead is the most boring experience in life.” “The ghost also had some very caustic things to say about contemporary literature. Because he just jumps into people’s heads and reads,” says Mackie with thinly veiled sarcasm. “There was a lot of theorizing about the ghost world that was completely lunatic, but it probably did sell books.”

Psychic Messages from Oscar Wilde found some success. It was published in the United States under the title Oscar Wilde from Purgatory—even 24 years after his death, there was the belief that Wilde had been so sinful that he was in purgatory.

Mackie says, “There was a combination of real and earnest admiration and a prurient fascination [about Wilde], and I think it’s that conjunction of things we would often think of as completely separate or disparate that leads to the weirdness.”

Wilde still wasn’t respectable, but he was on the road to becoming a legend.

Today, Wilde is seen as a sort of patron saint of queer history. He was incredibly famous and incredibly successful, and then in 1895 he was tried and convicted in what was arguably the most sensational criminal trial of the 19th century. Five years later he died of meningitis in exile in Paris, in poverty, in a drunken stupor. “He just collapsed,” Mackie says. “He’d had this really surprisingly large impact, and then suddenly nobody wanted to talk about him. It wasn’t until 10 years later that there was a little thawing of this ice age. People started to come out of the woodwork.” Wilde still wasn’t respectable, but he was on the road to becoming a legend. People wanted to have a story about him.

Beyond Travers Smith and her psychic disciples, there were equally flamboyant forgers who claimed to have had a personal relationship with Wilde and who produced letters and documents detailing said fake relationships. These forgeries promised to open up new vistas into literary and sexual history by looking at Wilde’s secret life.

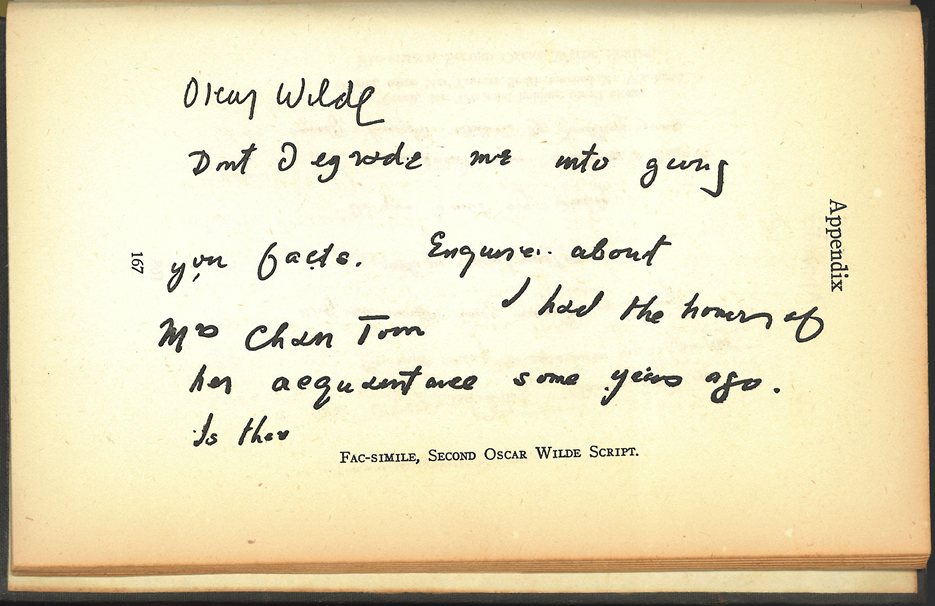

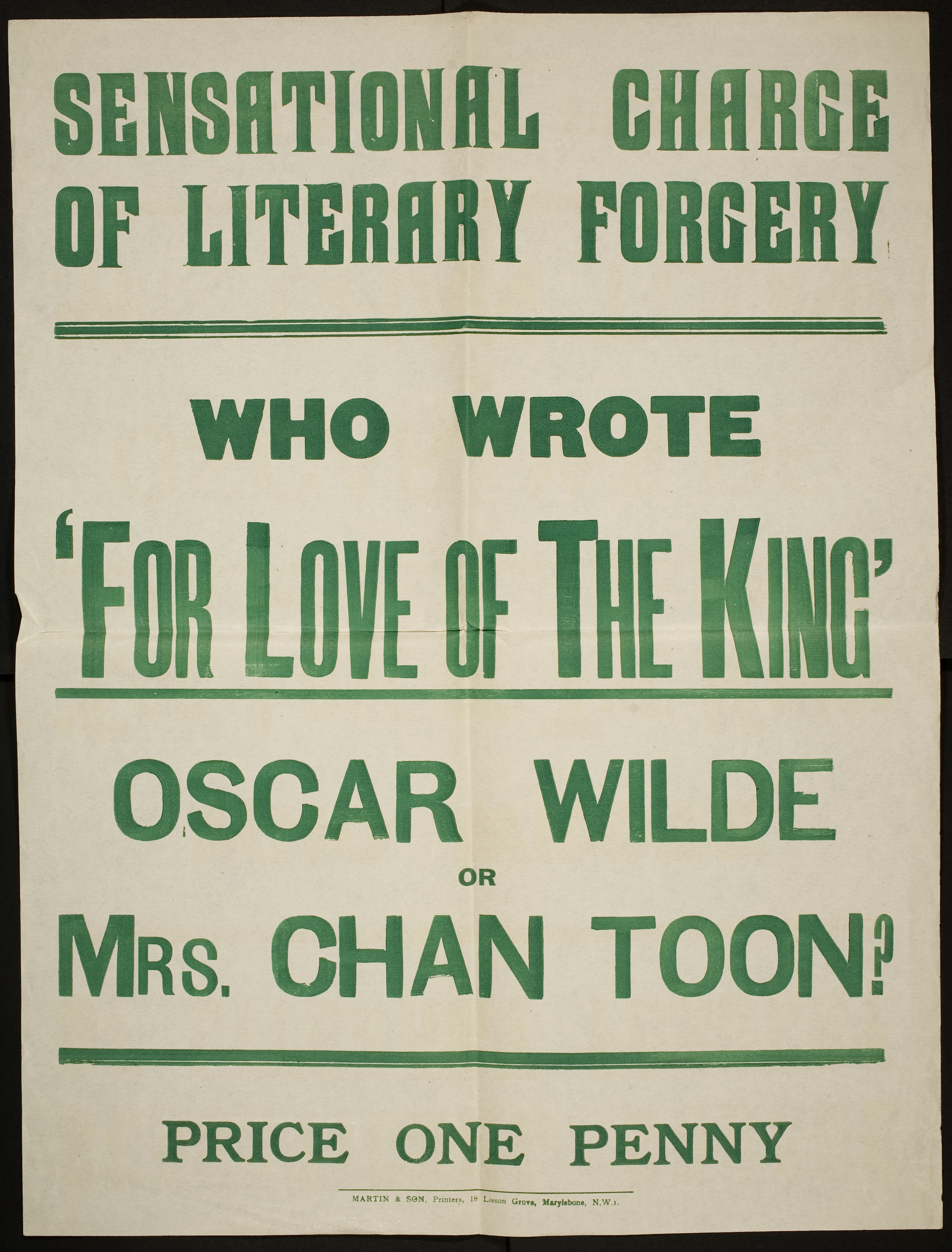

One such character, Mrs. Chan-Toon, went so far as to forge a play she claimed Wilde had written for her as a gift. The play was even published, and in the fraudulent introductory letter from Wilde to Chan-Toon, he writes of a dalliance with a Swedish baron. The baron never existed, but the inclusion of Wilde’s sexuality reinforced the readers’ will to believe that new secrets about Wilde were being revealed, new secrets about his sex life and about people that he was in love with. “Queerness is the ultimate authenticator,” Mackie explains, “the ultimate core, secret truth that is being revealed. The forgers are cannily aware that the ‘thing’ that is the most repressed and the most shameful at the time is also the most valuable because it is the most true, but of course, it’s a lie.”

“Sensational Charge of Literary Forgery,” 1925. William Andrews Clark Memorial Library , University of California, Los Angeles.

Chan-Toon is one of Mackie’s favourites. The process of researching Wilde’s afterlife has spanned more than a decade of his own life, and he’s been working with Chan-Toon for a long time. “She has a lengthy, legitimate bibliography of books that are so vanishingly rare that most of them only exist as deposit copies in the British Library. I don’t think anyone’s ever read them because they’re quite bad, but she did have a whole literary career.” But then that career collapsed, and she turned to a life of zany adventures and crime. She travelled the world; she did a speaking tour in the United States wearing a giant fur coat and loudly proclaiming that she weighed 250 pounds. She was arrested in Mexico for blackmail and claimed to have been in prison with Pancho Villa, the revolutionary. She wore a sweeping black opera cloak and had a parrot called Co-co perched on her shoulder at all times. “This parrot crapped all over it,” Mackie says. “She even went to court with the parrot when she was tried for theft in 1926, and there was all this media stuff about the parrot in court.

“Before that, though, she was desperate. So she made up this fake play and claimed to have known Wilde and claimed to have been at one point engaged to his brother. All lies, all fantastic lies. But people bought it. People were willing to believe these things about Oscar Wilde.”

Mrs. Chan-Toon with Co-co, 1926. William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

And so, Wilde lives on, memorialized in different ways by different people with different investments in his story. Mackie’s book examines forgery not to deliver finger-wagging blame, but to celebrate it as fan fiction. “I’m not interested in the ethical or moral aspect of it particularly,” he explains. “The forgers are expanding the imaginative universe of Oscar Wilde. It’s a kind of creative drag.”

Incidentally, there is a lot of dress-up and drag in the lives of the forgers as they attempt to capture and embody the aestheticism and decadence of Wilde when he was alive, in order to conjure him in death. One forger, an American from North Carolina with the moniker Dorian Hope, was the ringleader of a group of forgers responsible for a series of Wilde forgeries. He was a bad poet who was obsessed with the legacy of Wilde. “Definitely queer. He’d been a drag queen at the age of 19, and he died in 1934 in a car crash with a dashing naval officer at his side,” says Mackie with a raise of his brow.

He won’t say more because there is further research to be done on Hope, and we can expect a sequel to Mackie’s book that includes Hope. Mackie will reveal that after his Wilde forgeries, Hope became a fashion correspondent for an American newspaper syndicate and proceeded to forge the memoirs and letters of French theatrical celebrities. One of them does involve Wilde.

A picture of Dorian Hope (real name Bret Holland) and the announcement of his forgery scandal from the Washington Times, August 24th 1921.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.