Paula Amos on Indigenous Tourism and the Persistence of Female-Led Success in BC

Think global, act local.

“Hishuk’ish tsawalk.” In the eponymous language of the Nuu-chah-nulth—14 First Nations from the west coast of Vancouver Island—the philosophy behind this saying asserts that “everything is one.”

Passed down from generation to generation, the phrase is exemplary of the culturally rich oral traditions and histories of the Indigenous peoples of British Columbia—a unique province, considering it is home to nearly 200 different nations and 30 different languages.

“Hishuk’ish tsawalk” is also a lesson Paula Amos has carried from her youth into the work she does today. Amos—the chief development officer of Indigenous Tourism British Columbia (ITBC)—was the first and only employee when she started at the non-profit nearly 20 years ago. After completing her undergraduate degree in 2001 in both business administration and Indigenous studies at Vancouver Island University (VIU), Amos took a one-month contract at ITBC to set up the office, a board meeting, and then post a bid for a project assistant.

Before that, ITBC had merely been “a name and a 1-800 phone number with everything else in storage,” Amos recalls. She completed the task with such efficiency that she was asked to stay. Despite her intention of returning to university to complete her master’s degree, Amos stayed—and eventually grew the organization into what it is today: a thriving office with a board of directors and a reach far beyond anything she thought she’d see in her lifetime.

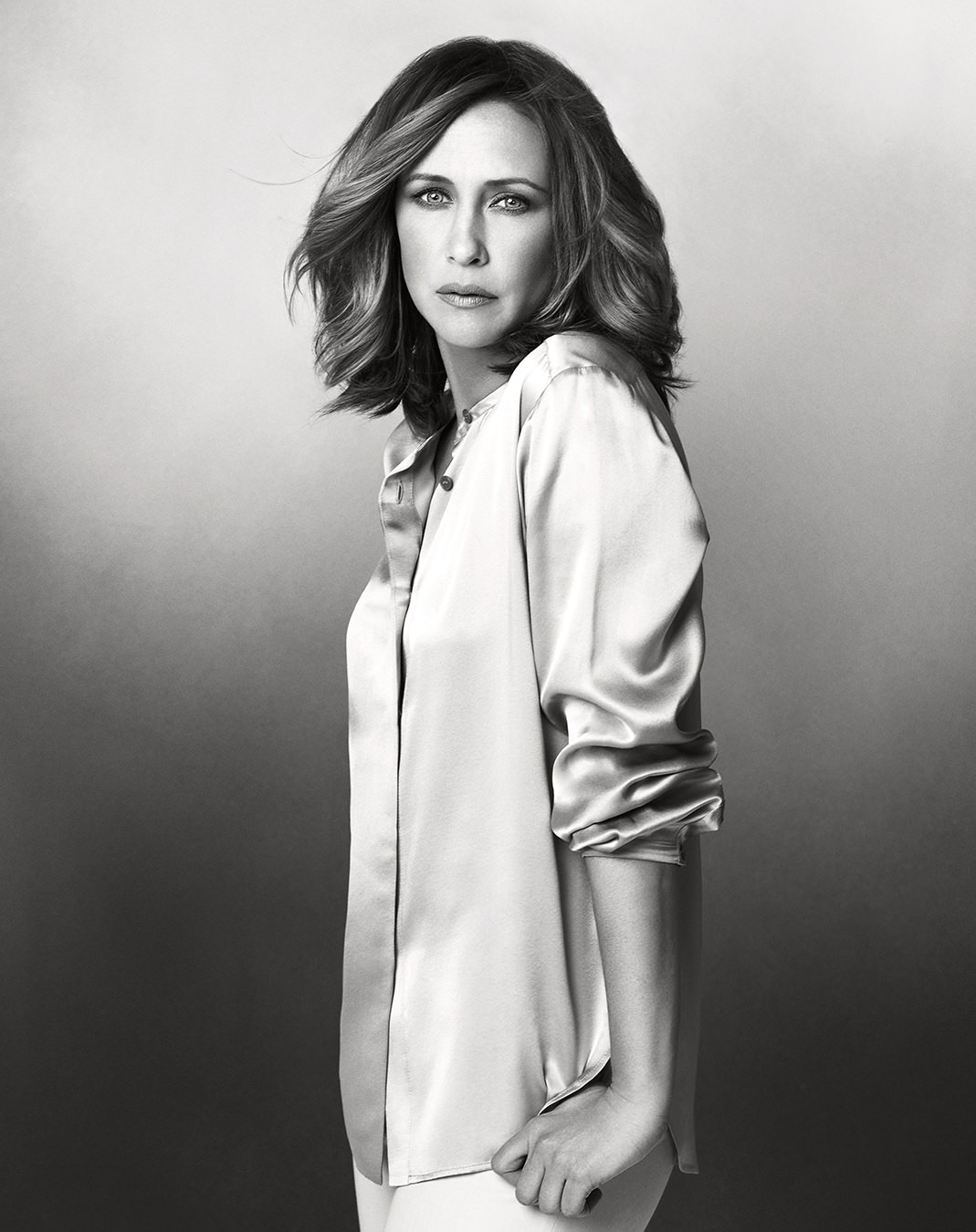

Portrait by Tracy Giesz-Ramsay.

ITBC works to build itineraries for group travel with a focus on exploring Indigenous culture and history. Emphasis is placed on Indigenous-owned and -led operations. This can be anything from a canoe trip to surf lessons—or even historical exploration of our difficult truths: Canada’s residential school systems. Interest in wellness, such as forest bathing—which is rooted in both Canadian and Japanese Indigenous culture—is adding to a widening curiosity of how nations thrived in this beautiful province before European colonialism.

“Hishuk’ish tsawalk” is also a lesson Paula Amos has carried from her youth into the work she does today.

Part of this expanding awareness, Amos admits, is due to her efforts during the 2010 Olympic Games when she worked with the North American Indigenous Games bid committee. “There was an Indigenous table we sat on to strategize so we could become a bigger part of the Games: to be part of the structure and not necessarily—how do I say this correctly—we weren’t going to be window dressing. We were going to be one hundred per cent partners in it; we wanted to work together.”

Those efforts led to Indigenous culture being broadcast to a global audience. Millions of viewers were encouraged to consider the concept of “hishuk’ish tsawalk.” At a time when we’re faced with the grim fact that our resources aren’t infinite—that humans actually have to restitute and tend to the ecological systems of the land to maintain such resources—the cultivation practices, philosophies, and traditions of our country’s true custodians couldn’t hold more importance.

“[Tourists] might go whale watching and not even know it’s an Indigenous experience. But then they go out [with one of ITBC’s partners] and they have a much deeper experience because they’re learning about how significant the whales are to our culture—or the connection that we have to the ocean and the water,” she explains. “Sometimes they get quite emotional when they have those experiences.”

T’sasa-a Dancers inside Big House at Alert Bay, B.C.

Indigenous knowledge can also be applied to another Western problem: the glass ceiling. In Nuu-chah-nulth culture, women were never seen as lesser-than or unable, Amos, who grew up commercial fishing with her father, tells me. “In our communities, women had equal—the word isn’t necessarily power—but importance, in our communities.” While women could still be guarded against a threat by men, “because they’re [physically] stronger,” Amos says, “it was the women who were giving the visions and the strategies behind the scenes.”

“In our communities, women had equal—the word isn’t necessarily power—but importance, in our communities.” — Paula Amos

Amos depicts the coming-of-age ceremonies the Nuu-chah-nulth held for Indigenous women as they entered their teenage years. Following a period of contemplation amongst their elders, the female is given a public ceremony meant to display respect and signal to the community her importance. It’s these inherent lessons of worth that have kept women like Amos strong.

“I’m fortunate here with ITBC: we do have a lot of strong females on the board of directors,” she notes, adding: “When you see the Indigenous entrepreneurs, there are a fair amount of women. When I was going to university, I was one of the first cohorts to go through the First Nations’ FNAT [now Indigenous Studies]; our classes were predominantly female as well.”

Chief among the underlying reasons for this female-led success is sustained intergenerational learning. “We’re fortunate that our elders still have that ingrained. [They] kept passing our teachings down to us.” Amos remembers going to her grandparents’ house on the Island, moving all the furniture to the side of the room, and participating in song and dance. “My great-grandparents were really instrumental in keeping our culture alive. I feel fortunate I come from that strong family.” For nations or families stripped of their lore by the residential school system, Amos is delighted to witness a revitalization.

“Over the years I’ve been here, I’ve seen youth have so much pride in the culture,” she says. “They’re educating the province and the world about who we are as First Nations Indigenous people. More and more, I see Indigenous youth and Indigenous elders making a great connection—especially with language revitalization. It’s really exciting to see that. That’s what really, really keeps me going.”

Spirit Ridge Resort, Thompson, Okanagan.

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.