-

Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas. Presented by Lord Taunton, 1864. ©The National Gallery, London.

-

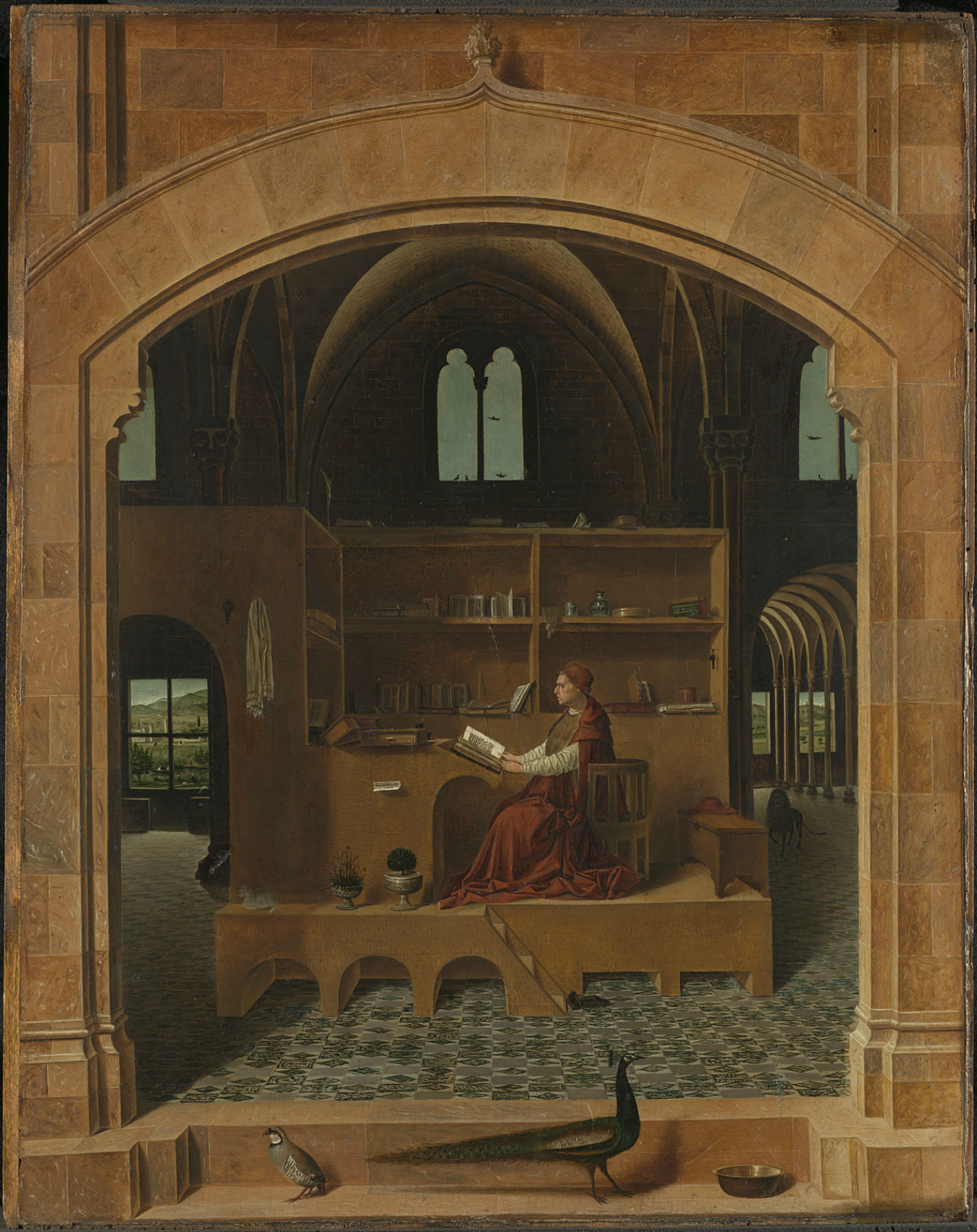

Antonello da Messina, Saint Jerome in his Study, about 1475, oil on lime. ©The National Gallery, London.

-

Sebastiano del Piombo, Judgment of Solomon, 1508–1510, oil on canvas. Kingston Lacy, the Bankes Collection (National Trust). ©National Trust Images/Derrick E. Witty.

-

Domenico Veneziano, The Virgin and Child Enthroned (Carnesecchi Tabernacle), about 1435–1443, fresco, transferred to canvas. Presented by the 26th Earl of Crawford and Balcarres, 1886. ©The National Gallery, London.

Building the Picture

Architecture in Italian Renaissance painting.

Putting backgrounds front and centre is the aim of Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting, an exhibition now on at London’s National Gallery. The result of a research partnership between the Gallery and the University of York, it presents a wealth of Italian paintings from the late Middle Ages to the High Renaissance. Its goal: to showcase the key, and often eye-opening, roles that architecture plays in Renaissance painting.

Among the oldest works on show is the Carnesecchi Tabernacle by Domenico Veneziano. Painted in the mid-1400s, it stood for centuries, exposed to the weather, on a Florentine street. A copy is set high about eye level over the archway that leads into the exhibition—the result shows how it would have appeared to passersby. (The original remains inside the exhibition itself.)

Architectural training did not exist back then, says Dr. Nicholas Penny, director of the National Gallery. Buildings and pictures resulted from artists with the same education in drawing and design. Some sketches show that many painters began by creating structures almost like stage sets, and only then drew in the figures.

On display are portraits of real places, such as a piazza in Florence, hybrid places based on real locations with a strong dash of artistic license, and completely imaginary places like the Jerusalem temple in Judgment of Solomon by Sebastiano del Piombo. The painting was possibly hung at the end of the grand hall in a Venetian palazzo, and the floor tiles depicted appear to shape-shift as you walk away from it.

Many paintings seem to invite the viewer in, to step over the threshold, climb steps, and look out through windows. Take the rooms, staircases, and a narrow street that leads the eye, beyond an arch, to distant trees in a luminous The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius by Carlo Crivelli. So skillful is the use of perspective that the image looks almost three-dimensional.

Architecture can be symbolic, as in numerous images of the Three Magi with the infant Christ—ruins signify the idea of an old order crumbling as a new one begins. Buildings can also represent ideas. In Antonello da Messina’s Saint Jerome in his Study, the small personal room is encased in a vast vaulted building. One of its messages: how translating the Bible lay at the heart of the huge mass of western Christianity.

Armchair gallery-goers can view the entire catalogue online, and watch five filmed modern perspectives on imagined architecture (including Martha Fiennes’s ground-breaking computer-generated Nativity) here. As Penny points out, the exhibition, “will turn anyone who sees it into a researcher.”

Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting is at the National Gallery in London, Trafalgar Square, until September 21, 2014.