-

The Mercedes-Benz Arrow460 Granturismo yacht.

-

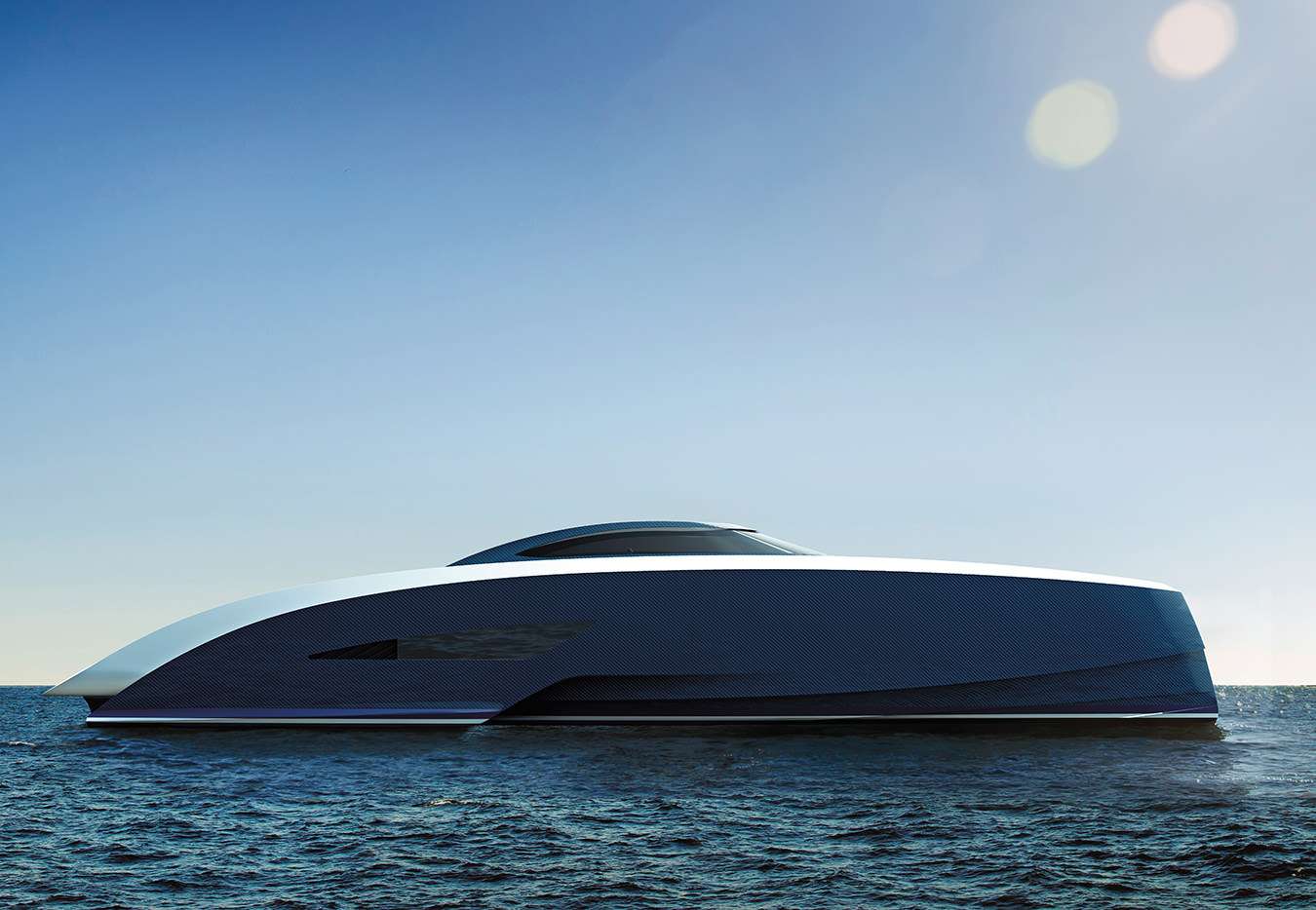

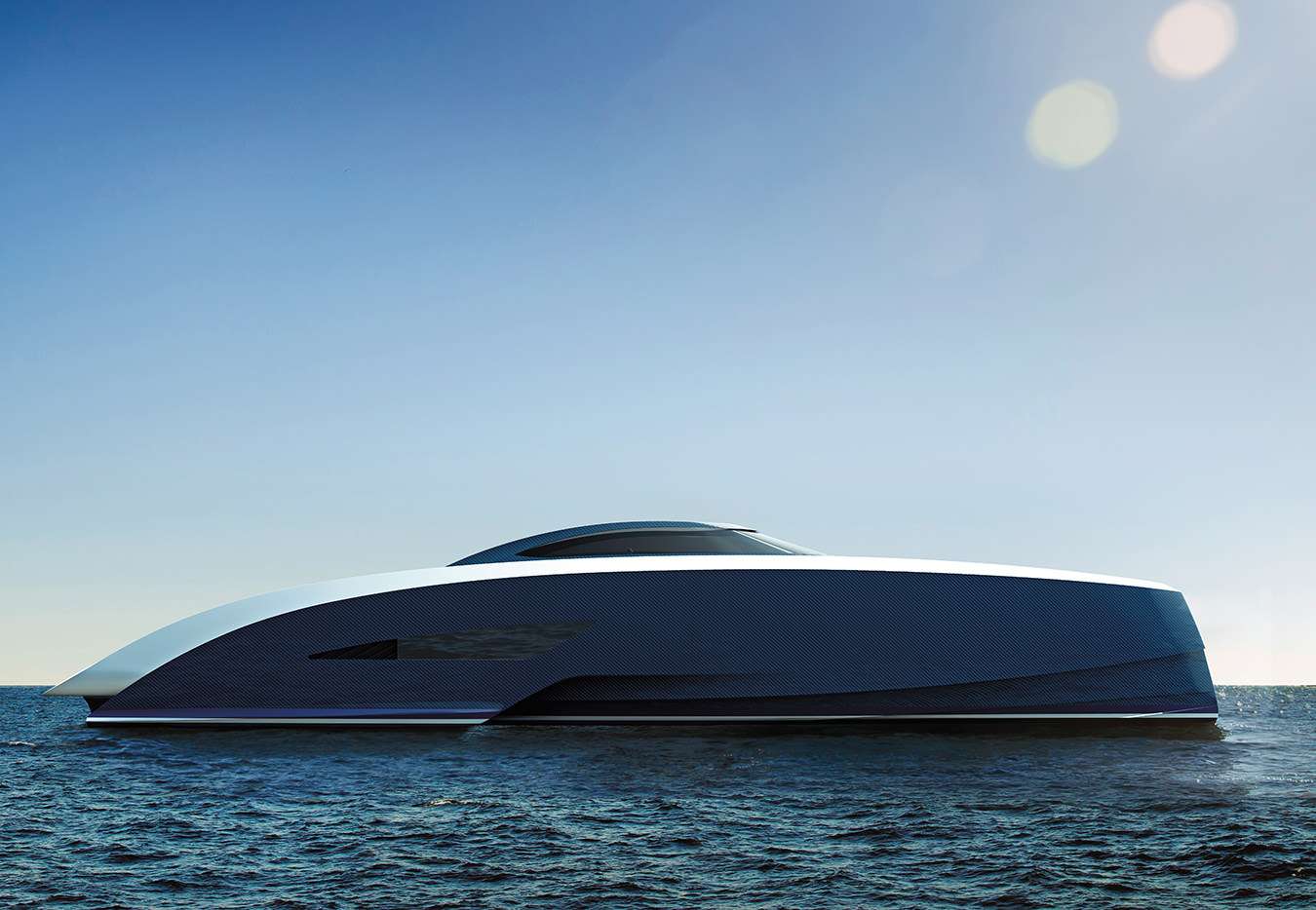

The Bugatti PJ63 Niniette yacht.

-

-

The Aston Martin Quintessence AM-37 yacht.

Luxury Auto Manufacturers Partner with Boat Builders

From street to sea.

In this age of ever-larger superyachts and, sometimes, extreme design, it’s hard to turn heads in the Mediterranean, Miami, and other boating hot spots. But this summer, two new boats look set to do so—and not because they are bigger or more outlandish than anything else on the water. Quite the opposite: both are modestly sized day boats, and both designs temper modernity with a subtle elegance.

What makes these boats—the AM37 and the Arrow460 Granturismo—so interesting is their pedigrees: AM as in Aston Martin and Arrow as in Mercedes-Benz Silver Arrows. It may be tempting, on seeing the names, to dismiss them as mere marketing exercises, little more than a cosmetic tweak with a logo slapped on. But that would be entirely wrong.

Both boats are the product of deep collaboration, involving some of the most respected individuals in the marine and automotive worlds (as does a third boat–car collaboration now in development between Bugatti and U.S.-based yacht builder Palmer Johnson). Signalling the seriousness of their approach, Quintessence Yachts, the Netherlands-based developer of the AM37, hired leading naval architecture firm Mulder Design for the technical design; the chairman of its supervisory board is Henk de Vries, director of Feadship, one of the world’s most respected shipyards. Aston Martin’s chief creative officer and design director, Marek Reichman, has been hands-on from day one. Among the heavy hitters on the Silver Arrows project are Tommaso Spadolini, who has designed more than 100 yachts in a 30-year career, and Martin Francis (who did the hull designs of Andrey Melnichenko’s Motor Yacht A, among others).

For almost as long as there have been cars, people have thought about making them float (indeed, long before cars, the Neapolitan prince Raimondo di Sangro is credited with inventing an amphibious carriage in 1770). But from the German Amphicar of the 1960s to the contemporary Gibbs Aquada and WaterCar Panther, amphibious vehicles have never achieved more than novelty value.

But creating amphibious cars is emphatically not the goal of these new collaborations. “The way [AM37] works is in many ways similar to a car, but it is not a floating car,” says Mariella Mengozzi, CEO of Quintessence Yachts. “Our first requirement was to develop an excellent boat from a nautical perspective and then to blend in [elements] that could be linked to the experience of driving.”

It may be tempting, on seeing the luxury brand names, to dismiss the boats as mere marketing exercises. But that would be entirely wrong.

Philosophically, these new marine–automotive collaborations have a lot more in common with the mid-20th-century idea of driving on the water. Indeed, the Riva Corsaro of 1946, based on the concept of a water-borne sports car, inspired a generation of Riva boats that became virtually synonymous with la dolce vita. Across the Atlantic, Chris-Craft’s Freedom Fleet of fast and elegant wooden runabouts tapped into Americans’ enthusiasm for convertible cars; a 1958 advertisement described the firm’s 19-foot sport boat (called the Silver Arrow, coincidentally) as “a sports car for the water.”

Equally, car design has long been inspired by boats: barchetta (little boat) models date back to at least the 1925 Fiat 509 SM. In 2003, when Rolls-Royce introduced its 100EX (the precursor to the Phantom Drophead Coupé), its chief designer, Ian Cameron, described the many ways in which it had been inspired by the J-Class America’s Cup racing yachts of the 1930s.

Given such affinity between the two worlds, the real surprise is that any serious automotive–marine collaboration has taken so long. Even Ettore Bugatti, despite his deep interest in boats (he designed engines and propeller shafts for speedboats, and, in the 1930s, set speed records in his own boats, Niniette I and Niniette II), never explicitly linked his boats to his car business.

That has been left to Bugatti in its modern incarnation, and yacht builder Palmer Johnson. Announced in December 2015, the project—called Niniette in honour of Bugatti’s boats—comprises a series of three open sport boats, 42 feet, 63 feet, and 88 feet. More aggressively modern than either the AM37 or the Arrow460 Granturismo, Niniette’s design is based on Palmer Johnson’s groundbreaking SuperSport series of carbon-fibre monohulls. The Bugatti design team’s renderings show references to the Bugatti Type 57C Atalante and Type 41 Royale in the lines and proportions. Prices will begin at €2-million ($2.9-million Canadian) for the smallest model, with the first boats expected in the water by summer 2017, if not before.

This summer’s new boats (the first Arrow460 Granturismo was launched in mid-April and, shortly afterwards, the AM37 went into the water for testing) both sprang from a desire to bring something fresh to yachting, particularly in the day-boat range, a sector that has remained surprisingly conservative for decades.

The two have much in common: both are being presented as Granturismo models. High performance is a given—the AM37 is capable of 47 knots (87 km/h)—but never at the expense of comfort, safety, stability, and great handling, exactly like the cars that have inspired them. Both developers have made a point of using their automotive partners’ suppliers for interior components, partly for the tried-and-tested quality and partly, as Mengozzi puts it, “because we felt that they could make a difference to the look and feel—inject some true automotive DNA.”

The seed for the Silver Arrow project was planted in 2008, when Mercedes-Benz approached Monaco-based Paolo Bonaveri (a marketer and former journalist with connections in the car and yacht industries) and then-employee Giorgio Stirano (a former Formula One engineer) and asked, as Bonaveri puts it, “if there could be an opportunity in the marine sector where Mercedes could extend its portfolio after the Eurocopter project.” (The newly formed Mercedes-Benz Style division had designed a special VIP interior for the EC145 helicopter.)

“It took me 10 seconds to say, ‘Yes, it’s possible,’ ” says Bonaveri. He assembled a team and got to work. But when the financial crash was followed by a collapse in the yacht business in 2011, Bonaveri—along with Stirano and current Silver Arrows Marine CFO Guido Pedone—went back to Stuttgart and recommended starting over: “We told them we should form a new company and we had found investors.”

That company is Silver Arrows Marine, named after the great Mercedes and Auto Union grand prix cars of the 1930s.

Given such affinity between the marine and automotive worlds, the real surprise is that any serious collaboration has taken so long.

The automotive and marine sides of the project quickly began to merge. “Martin [Francis] and Tommaso [Spadolini] did a lot of research on the hull and cockpit and helped the designers at Mercedes to understand the proportions and other [requirements] of a boat,” says Bonaveri. “The Mercedes team learned very fast and increasingly took the lead. They poured all of the potential, skills, and power of Mercedes into it. At one point, they had five research and design teams working on it.” The specialized naval architecture work remained fully in Silver Arrows Marine’s hands, however.

The original idea had been to build a 38-foot boat, but, says Bonaveri, “We soon realized that, to relate properly to the car—our models were the S-Class Coupe and Cabriolet—we had to go bigger [to 46 feet].” Not only bigger: as the team’s ambitions to completely integrate the marine and automotive elements grew, so did the complexity of the project. “This small boat has been almost as complicated to design as a superyacht,” laughs Bonaveri.

One example: reconciling the decision to design a tunnel hull for performance and stability with the Mercedes designers’ wish to closely echo the aesthetic of a car body. “Translating the cutlines of a car body to the waterline and then combining this with the naval architecture of the hull was very challenging,” explains Bonaveri. “All of the cut-lines on the hull have to follow a ratio established by the cockpit. And the triple-ratio curves of the glass and floor had to follow this too. Also, the designers wanted a completely smooth bow, with no cuts or openings for the anchor, which meant developing a completely new anchoring system from scratch.”

The result is a hull shape so complex that the mould has to be made in four pieces, not one, greatly multiplying the production cost. The team opted for an ultra-light and strong prepreg carbon-fibre composite used for racing yachts such as the TP52 and America’s Cup classes and turned to a world leader in the technology, Switzerland-based Décision S.A., to develop and build the first hull.

There’s more: to flood the boat’s interior with daylight meant designing windows that extend three metres on each side of the superstructure, with a double curvature. The central window in the front is not only double-curved but opens up “like a pergola” to create an uninterrupted indoor-outdoor flow. To keep the interior sleek, without blinds or curtains, the designers adopted the technique used inside the roof of a Mercedes SL, applying a layer of silky mesh to the inside of the glass.

“Six years ago, we had only a vision that we didn’t want to do anything that had come before,” explains Bonaveri. “We are still learning what that could be, but at this point we’re happy because we really have designed a car in a boat and a boat in a car.”

As Mariella Mengozzi explains, the goal of bringing something new to yachting was the very purpose of establishing Quintessence Yachts. The company approached Aston Martin in 2013 with a concept just as the British carmaker was exploring other avenues for developing its brand. With the decision made to collaborate, Quintessence immediately turned to Bas Mulder to design the hull, since “the primary requirement of a boat is that it performs well,” says Mengozzi. The naval architecture, she adds, was “quite straightforward. Bas has immense technical knowledge and immediately understood how to interpret our concept.”

For Aston Martin, the project was, initially, harder to grasp: “The approach Aston Martin takes in its core business is not easy to translate to another industry,” Mengozzi explains. “In everything they develop, they search for the limit and try to push themselves past it. Not to do new and difficult things for the sake of it, but when it makes sense in the final design and in the owner’s use of it. And that is the core of the collaboration: really understanding where we are coming from, what we want, and why we want it.”

What Quintessence wanted explains the choice of a 37-foot boat: it had to feel very close to the sea and be comfortable, fun, and manageable for a solo user, says Mengozzi. “And also big enough to show its beauty and style—which is important from a brand perspective.”

Quintessence and Aston Martin’s shared wish to design something pure and essential added to the challenge. Mengozzi cites the windscreen as an example: “We all looked at the design and said, ‘Oh, it’s so beautiful,’ but then we had to figure out how to make it in a single piece with all of the different curves.” But, she says, an even greater challenge was the cockpit. “It’s a paradox: that part of the boat is most like a car. But because of the functioning of a boat, the driver is standing, sitting, has to be free to move—it’s the exact opposite of a car.”

The Aston Martin Quintessence AM-37 yacht.

“Our first requirement was to develop an excellent boat from a nautical perspective and then to blend in [elements] that could be linked to the experience of driving,” says Mengozzi.

Mengozzi was surprised by how deeply Aston Martin became involved in the project: “Marek [Reichman] and his team are amazingly open to learning, and their commitment was so much more than with other licensing partnerships I’ve worked on. [Mengozzi was previously with the Walt Disney Company Italy and Ferrari.] The collaboration went very deep into the content of the project; it was never a case of ‘We develop, they approve,’ which is more usual with licensing.”

Perhaps the most obvious wow feature of the AM37 is its convertible hood, which consists of carbon-fibre panels that slide over the cockpit to lock the boat closed when it’s not in use, as well as a carbon-fibre Bimini top. Although the automated slide-lift-fold operation closely mimics the movements of the roof of a convertible sports car, it was developed by Quintessence, not Aston Martin. This, the retractable swimming platform, and other similarly suave features added a huge layer of complexity to the boat (“We need 20 separate actuators for operating all of the moving parts,” says Mengozzi), and yet the overall impression is of great simplicity and elegance.

There’s a sense, in talking to both Mengozzi and Bonaveri, that they almost had themselves in mind as their typical clients. This is no bad thing: the creators of many great products (especially in the luxury space) have taken the approach that, “If I like it, I believe there are many other people who will.” But who do they think will buy their boats? Both say that buyers may already own a superyacht and use the smaller boat as a super-tender or chase boat. (The first buyer of an AM37, reveals Mengozzi, already owns Aston Martins and other boats and will base his new toy in Miami.)

Where they differ is that, while Mengozzi says her clients “may be people approaching boat ownership for the first time, who like the mix of content and style,” Bonaveri asserts that the Arrow460 Granturismo “won’t be a first boat. The client will probably be upgrading from an existing 20-metre or 25-metre day boat. This is not just the big toy for a big boy with money. It needs a special understanding to appreciate what this boat is.” It will, naturally, require money as well—around €2.5-million (approximately $3.6-million Canadian) for the Arrow460 Granturismo. The amount for the AM37 was not disclosed at the time of going to press.

The two firms’ production plans are different as well: the Arrow460 Granturismo will initially be produced in a limited edition of 10, with “same specs, same colour, same option,” says Bonaveri, adding that they will be selective about the clients’ locations: “We don’t want them all concentrated in one or two places.” Mengozzi, on the other hand, has no plans to make limited editions, although production will be limited by the builder’s capacity to between 10 and 20 boats a year, she expects. “We don’t want to set limits on numbers or time,” she adds. “We are absolutely convinced that the AM37 has a long-term future, that it will become a new classic.”