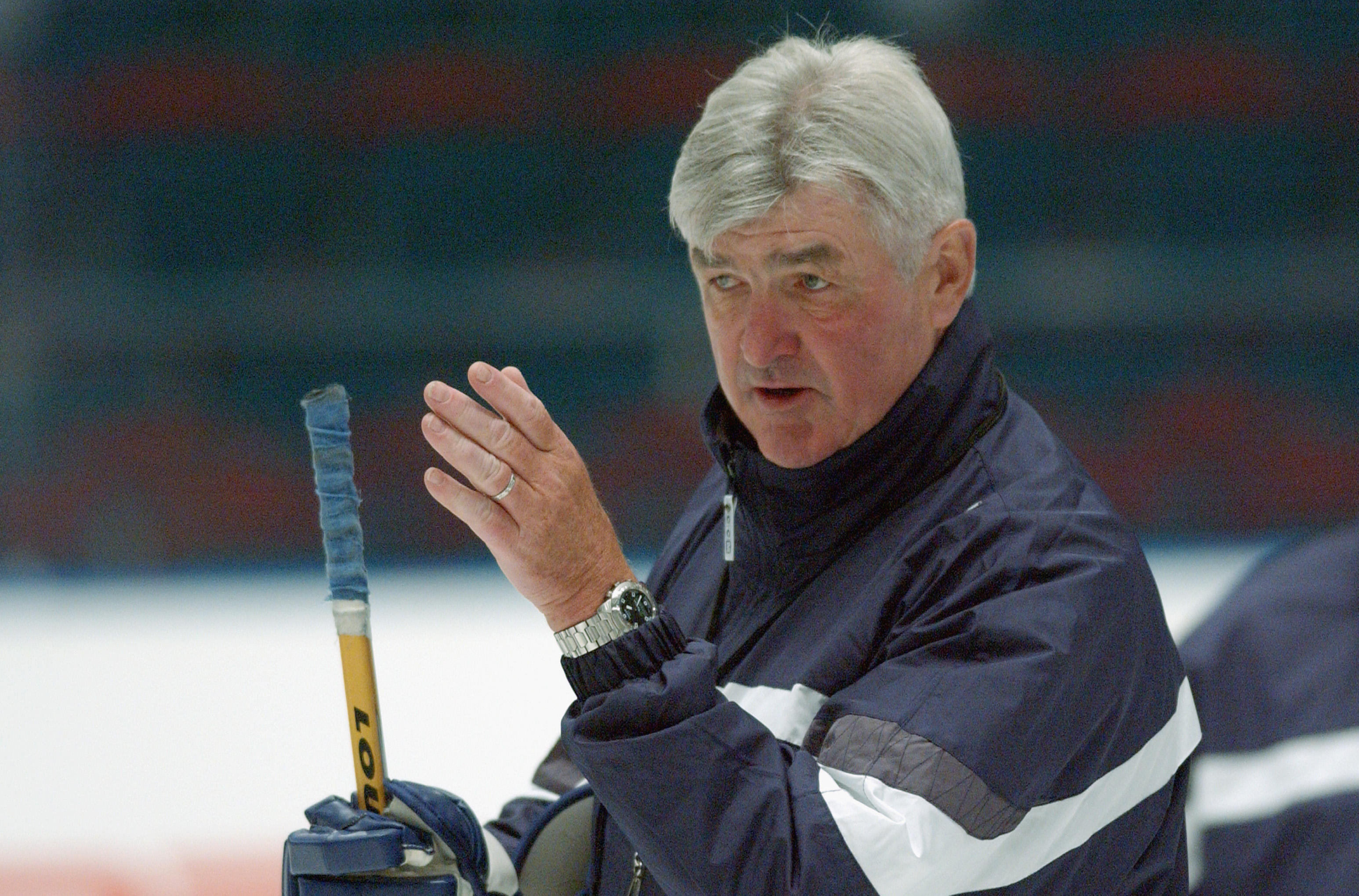

Pat Quinn

Quinnology.

The first player on the ice at morning skate, 10:00am of a Hockey Night in Canada Saturday in the middle of winter, is defenceman Robert Svehla. He is closely followed by Thomas Kaberle, Tom Fitzgerald, and skyscraper Nik Antropov. From there, players arrive to cut their grooves in the surface in small batches of three or four, the pristine ice marred and scarred in short order as they make their various moves. It is the exact replica of game time, lights blazing, popcorn odours already wafting through the cavern, pucks popping into the boards, onto sticks, into mesh. Rick Ley and Keith Acton arrive, and before long the chaos runs to order, as players assemble for first shooting, then passing drills, and finally, in a quick and seamless choreography, into various graduated defense drills: one on one, two on one, three on one, three on two.

Every drill has components of passing, turning, positional play, man on man and zone coverage. They don’t waste a second, because they have 45 minutes until the ice needs to be resurfaced, so the big bad Rangers can take their own pre-game skate. Pat Quinn, it must be noted, does pointedly not take the morning game-day practice ice, having led the team meeting that precedes it, planting in players’ minds what they need to focus on this day.

He is involved in all things Leaf. He has duties as Coach, but also as General Manager, reporting to President Ken Dryden, for the storied Toronto Maple Leaf hockey team, one of the two Canadian Original Six teams, along with Les Habitants, subject of great scorn but recipient of fervent admiration in equal measure all across the land, including the other Canadian NHL buildings in which they play. Roch Carrier’s grand story, “The Sweater”, is possible only because the kid on the frozen pond in rural Quebec receives not his Rocket Richard bleu, blanc et rouge, but horror of horrors, a Maple Leaf sweater. No other sweater could arouse such simultaneous hate and compassion.

Montreal Canadiens fans, particularly those who followed the team’s glory years in the 1970s, will carry with them to the grave the gentle but persistent irony that their revered goaltender, stealer of Stanley Cups and bestower of expected dignity in the crease when the team was riding high, is now the President of the Leafs, but there you have it. Hockey is a great game, but it is a vast enterprise as well, no longer in the sense Bill Wirtz, Conn Smythe, and others handled it, but as an intricate, vital organ in a big city that has not yet and most likely never will outgrow it. Quinn straddles the line between business and game, in some ways the epicentre of all the activity, on and off the ice, that makes the Air Canada Centre hum. He even allowed a photographer onto the hallowed ground of the pre-game dressing room speech on the ACC’s opening night. [This photo was part of a special project to commemorate the rink’s opening night, called A Day in the Life of the Maple Leafs, a book that represents in pictures exactly what a writer would want to accompany an article.] Bump into him in the back halls, though, and he seems like what you imagine he was like as a young player, jovial, exuding charm and friendliness, but always knowing the business end of the stick. “Don’t let these PR guys fool you,” he says, “I’m a pretty relaxed guy.” Nods and either winks or winces all around, before he adds “especially when we win.”

Pat Quinn knows the score. “It’s a profession where people lose their jobs on a regular basis. I’ve been very fortunate to be asked to do something new each time it happened to me.” He never seems to lose sight of this, with his assistants, with his players, with himself.

The skate has its whimsical elements, Alex Mogilny testing not one or two but half a dozen sticks, Mats Sundin studiously keeping to himself whenever possible, working on moves against imaginary opponents, Shane Corson actually testing backup goalie Trevor Kidd pretty sternly as the time winds down. Darryl Sittler, looking like he could easily suit up that night, comes to the boards for a few words with a couple of the players. Harry Neale is deep into his notes for the television broadcast later, but when he rises from his seat, a group of grade school kids yells as if on cue “Hey Harry”, and he stops by to tell an entertaining story or two, like the time he saw Sittler score 10 points against the Boston Bruins, or the time he tripped on an electrical cable and nearly toppled out of the Foster Hewitt press gondola, fifteen stories above. The kids love it all, and the strict veracity is simply not the point, though Sittler still holds that single-game point record.

As the Leafs pile away their gear, get ready for their pre-game meal, the opposition is taking the ice. The media is now more in evidence, wanting to have a word with the big-ticket boys on the big-ticket team run by Glen Sather, who has himself just come round the corner, genial and relaxed, taking Bob Cole’s arm, saying “Let’s grab a chair and watch, Bobby.” Mike Richter is a surprisingly small package, though his thighs must be about 36 inches; Pavel Bure is bigger, and has that natural athlete’s easy way of movement; Brian Leetch is matter-of-factly striding to the ice, where he seems to move easily as if he were suspended in space; Eric Lindros, well, there’s no accounting for the effect of seeing him come out of the dressing room and head down the tunnel to the ice, on skates a surreal giant of a specimen. Actually the Rangers as a team look immense on the ice; Leafs fans quietly hope the balance will be swayed by more than simple physical force. And usually it is. Islander legend Bryan Trottier, in another piece of gentle irony, is the Rangers’ coach, clearly what they call in the trade a “player’s coach”, demanding in a jovial kind of way that suggests many years surrounded by elite athletes, such as he himself so clearly was. Teddy Green, one of Bobby Orr’s steady teammates, and Jim Schoenfeld round out the coaching corps, and their skate seems a bit more structured than the Leafs’ but with a somewhat diminished energy component. Perhaps this goes with the territory as visiting team.

Under the stands in the Media Centre, Pat Quinn makes his first public appearance of a very long day, fielding ten minutes or so of pre-game questions with splurging wit and anecdotal evidence that he has seen plenty in his time. And a long time it is. Quinn’s junior and minor league days, in Knoxville, Tulsa, Memphis, Seattle, were in the early and mid-60s. He turned pro, with these same Leafs, in 1968, in time to play many times against Bobby Orr, whom he tattooed into the boards one evening in Boston, for which action he had to answer with his head distinctly up. Not that this would have bothered him. As a player he was tough, sensible, knew how to find the outlet pass, and could skate backwards better than most. There might have been a temper and a touch of the mean streak in him, as well.

Quinn remembers those days well, the teammates he had, and it informs his coaching style to this day. “I know these players are capable, and I think we’ve got a pretty good team. But the puck starts to scare them when they’re not going well. In the old days, one mistake and you were gone to the minors. Guys like Mike Pelyk, Jim Dorey, Ricky Ley, even Jim McKenny, a tremendously talented player, were always one bad shift away from a weekend or more on the bus in the bush leagues. But we don’t want to do that here.”

From the Leafs he went to Vancouver, then Atlanta, where he captained a second new franchise and helped them in their inevitable baptism by fire. A solid playing career ended 606 games, 18 goals, 113 assists, and 950 penalty minutes later, in 1977. After a brief hiatus, he joined the coaching ranks in the big leagues, with Philly in 1978. He remembers that Flyer team fondly: “They were just a great bunch of guys who hated to lose. They were motivated, every night. Five or six high quality players; Bobby Clarke was nearing the end of his career, and was still a force, and a great leader. Billy Barber, but really, there were more talented teams in the league.” In 1979-80, his Flyers lost only 12 times, the third-lowest total in history. They also set the still-standing record 35 games undefeated. His admiration for that group of players is abundantly evident today, as he reminisces after an off-day practice. Something about self-motivation and team play, both recurrent themes in his hockey life.

Quinn moved to Vancouver in 1990, after three years in Los Angeles, and already enriched with a law degree. “I like to read, basically. And what I read at law school was bound to be helpful, no matter what I did in future.” He brought stability to a team that had 11 consecutive losing seasons under its belt. He turned things around, there, and took the Canucks to the Stanley Cup finals in 1994, losing to a hot Mike Richter and an obstinate crossbar in game seven. The Leafs came calling in 1998, and the team has pushed near a .600 winning percentage ever since.

This though, doesn’t help them as they struggle through a dismal homestand early in the 2002-03 campaign. Games seemingly slip through their grasp night after frustrating night. A late penalty and a last-second goal against, two or three goalposts at the other end, and soon enough the players are, as they say, “squeezing their sticks too hard”. The unmistakable element of hockey glamour, in the guise of Hockey Night in Canada, Ron MacLean, Don Cherry tucked away in their Coach’s Corner set just off the Leafs dressing room, adds to the evening’s luster. Big camera units, big lights, big press crowds, plenty of early fans hoping for a glimpse of stars and personalities, creates a nice buzz even 90 minutes before the puck drops.

Turn a corner in the maze of hallways around the team dressing rooms about 40 minutes before ice time, and you might hear a fusillade of tennis balls. Turn another corner and there is one man, Eddie (the Eagle) Belfour, pounding two tennis balls off the floor, onto the wall and back into his two waiting hands, almost more rapidly than the eye can follow. It’s a magic act of hand-eye co-ordination; he pauses slightly, to let me pass, but his mind is moving on silence, like Yeats’ long-legged fly, readying him for what is coming his way in less than an hour.

Other players ritually check sticks, blades, tape, how the jersey hangs. Pat Quinn himself shows up for the pre-game speech exactly five minutes before puck drop. Never more, never less, precisely calibrated to the time it takes him to leave his office and make the short distance to the dressing room.

The Ranger game proves no respite: the home side outplays and outworks the Broadway Blueshirts, but a right side defensive collapse at the 15-minute mark of the third allows a tying goal on a third rebound, and then, in a shocker that silences the entire building, a giveaway up the middle with 40 seconds left springs Pavel Bure, brooding quietly all evening, in homefree to score the winning goal. Ken Dryden bolts from his perch that night, and the local scribes shake their heads in unison. “What will Pat say?”

Ten minutes later, at the post-game press conference, he is very calm, a close approximation of being relaxed, as he fields the questions which, after another stunning loss, seem almost gentle. “We have some rookies in the lineup who hurt us a bit tonight, but we knew that would happen. We were patient with young guys like Kaberle and Antropov in the past, and look how well they play now. But its not the young guys, it’s the veterans that have to rise to the challenge, to overcome this stuff. They’ve seen it before, they’re supposed to be able to beat it.” He chats on, the players by now already filtering out into the night in snazzy street clothes, great watches, great shoes.

The dressing room is very nearly luxe, with its pure maple stick stand, separate equipment and dressing rooms, high-tech machinery and staff to take care of every little thing. Press flood the room when the doors open, a few minutes after the game ends. Bright lights and microphones proliferate, and everyone seems to take their turn. Game stars, or at least focal points for the game’s unhappy narrative, are most in demand. And of course the superstars, of which the Leafs have several. But this night Mats Sundin, who was thwarted in a game-tying attempt with four seconds left on the clock, and who demolished his graphite stick on the Ranger net as the game ended, is nowhere in sight. Uncharacteristically, Alex Mogilny is talkative, taking it upon himself to say better days are just around the corner. Everyone eats it up; Alex is reticent, but there always seems to be a gleam in his eye and a shadow of a smile somewhere.

By the time midnight rolls around, the rink is finally silent and dark. Tomorrow is a practice day, at Lakeshore Lions Arena, where the players preceding the Leafs are a Bantam league team, not any less earnest on the ice for that. Ed Belfour is first out, testing a muscle or two that may have twinged the night before. As is true every day, the goalies’ stretching regimen is intense, extended and careful. By the time they actually take a shot, they’ve already put in a serious workout. There is a lot of defensive zone work today, Quinn mapping things out on a board, watching most intently at the defence pairings as they face a full five player assault. There are even a few apparent mishaps, Alyn McCauley’s nose broken on a teammate’s shoulder, Darcy Tucker running Bryan McCabe into the boards harder than is strictly necessary. McCabe is still fuming as he makes his way to the parking lot, half an hour later. But Quinn smiles lightly when asked about the frisky practise: “I didn’t really notice anything untoward out there, to be honest.” He mentions to me later that Arthur Griffiths is in Toronto for meetings, and that it will be nice to say hello to him, and off he goes into the midday bluster of a Lake Ontario wind.

Next night, the Mighty Ducks of Anaheim are in town, the real ones, not led by Emilo Estevez and crew but by Paul Kariya. Paul is a main attraction everywhere he goes, but in certain hubs of hockey he attracts crowds, of kids, adults, press, opposition players even. He politely does his routine before and after skating. His team proves to be the panacea the Leafs need. That evening the game is not, strictly speaking, an even affair, 5-2 Leafs the final. A collective sigh of relief goes up when the game is over, though Ken Dryden again bolts from his perch in the gondola. George Armstrong, legendary Leaf, is all smiles, as is Darryl Sittler.

Alex Mogilny is “a very gifted player” Quinn asserts, relaxed in his office after the game. It is two valuable points in the standings, and Alex scored the pretty game winner. “But he is a true enigma. He can play the game any way he wants, and basically be the best at it. He’s one of the toughest guys to move off the puck I’ve ever seen. But he’s a contemporary type player. You don’t always know until the game starts what’s going to happen. The pressures today are a lot different, too, so it’s hard to know exactly what motivates any individual player. We preach a dedication to the team concept, and that in turn, at least theoretically, leads to a desire to perform at a high level as an individual, as part of a team.” Quinn pauses only momentarily, needing very little to coax entended comments that entail his experience and his unrepentantly positive approach.

Just a few moments earlier, he had been doing a post-game call-in show with Harry Neale, called “Pat’s Point”. I enter the studio with Pat who says “Harry, Jim’s just gonna sit in and listen.” Harry says, “No problem, I met him earlier actually. But Jim, this is live on air so remember, no farting.” The room breaks up as usual when Harry tells a joke. Harry gets a couple of e-mails, and reads them to Pat, who answers. The whole affair is simulcast on radio and the internet. When asked who his role models were as a player, Quinn did not hesitate: “Doug Harvey. I had the chance to play with him, and be coached by him. Most important lesson I ever learned as a defenceman was from Doug: ‘get the puck quickly, and get rid of it quickly, let the other guy screw it up’”. Pat and Harry both laugh, thinking no doubt of the old days, when teams knew their opponents intimately, and toughness wasn’t only for an enforcer or two. He is then asked if he could play in today’s NHL, and considering his playing weight of 220 and his height, 6’2”, you might think it a dumb question. But not Quinn. “Well, it’s not so much that I couldn’t handle the size, though that would be a challenge. I was big for the league when I played, but today I’d be small guy on the program. But, I could always skate backwards very well, almost better than forward, when I think about it. And that outlet pass, there’s Doug Harvey again, I could usually find the outlet pass. So, yeah, I think I could play today. But it is more of a size, speed and skill game than ever now, so it would be a challenge.”

For him, the central component is not to motivate players, but to train them how, and why, to motivate themselves. “I think of that Swedish kid you guys have in Vancouver, that I traded for. When he arrived, his confidence wasn’t what it needed to be, but I always thought he’d be a great player if he could bring himself to that level of desire, and commitment. And now look at him. He’s done it pretty much on his own.” The Swedish kid is Marcus Naslund, who won’t be suffering a crisis of confidence anytime soon.

However, Harry Neale tells the story of Wayne Gretzky, the year after he had scored an imponderable 90 goals and 212 points in a single season. “He came up to me one day at the rink and said ‘Harry, you know what? I just don’t feel good out there right now. I’m not sure what the puck will do next.’” Harry’s advice? “Wayne, every player, even the best, goes through times when he thinks he’s not as good as he really is. The great ones work through it faster, that’s all.” Quinn seems to intuit this in his players, when they need cajoling, or something more forceful. But on the practice ice, he never truly raises his voice, even. He wants players who, like he constantly says about his 2002 Olympic gold medal team, “play the game, and think the game.”

The building darkens down, the odd employee still taking care of his or her portion of the load, as Quinn waxes a little philosophical: “Each player has his own lock, and it’s not always easy, not even always possible, to find the key. The game tests a person’s mental toughness, and my job is to know how and when to test a player, so that they learn that toughness.” The phone rings, and he smiles. “if that’s my wife, you’re going to be in big trouble, keeping me here late.” But it’s another hockey business professional, Dryden, on the line, and a late night chat is going to get later.

It is impossible to meet a living hockey legend such as Pat Quinn and not ask a cherished question or two strictly from a fan-from-the-cradle perspective, and he appreciates the fact. His estimation of the best hockey team ever? “Well, I loved that Flyer team, and the Gretzky Oilers were great. But, over the years, I’ve always believed in the team for team’s sake concept. The Montreal teams in the mid-70s had that, but they were also loaded with all that awesome talent. Just the defense: Savard, Lapointe, Robinson. Dryden in nets. And all these hall of famers up front, Lafleur, Lemaire, Gainey, and on and on. They didn’t lose too many games those years, and that takes more than talent. And four Cups in a row. So I might pick those guys.”

He moves easily down the hallway, into the long shadows of his hockey rink at rest. Hip surgery, knee problems, shoulder problems (“I get a new suit made, and I usually look like Quasimodo”) have all taken their toll. His fairly recent health scare has forced him to lose weight and attend much more closely to his diet, but all those years of practicing mental toughness have stood him well in these circumstances. As he rounds the corner, out of sight, he leaves the impression of an athlete who will never truly grow out of his love for the game.

Photog by Dave Sandford/Getty Images.