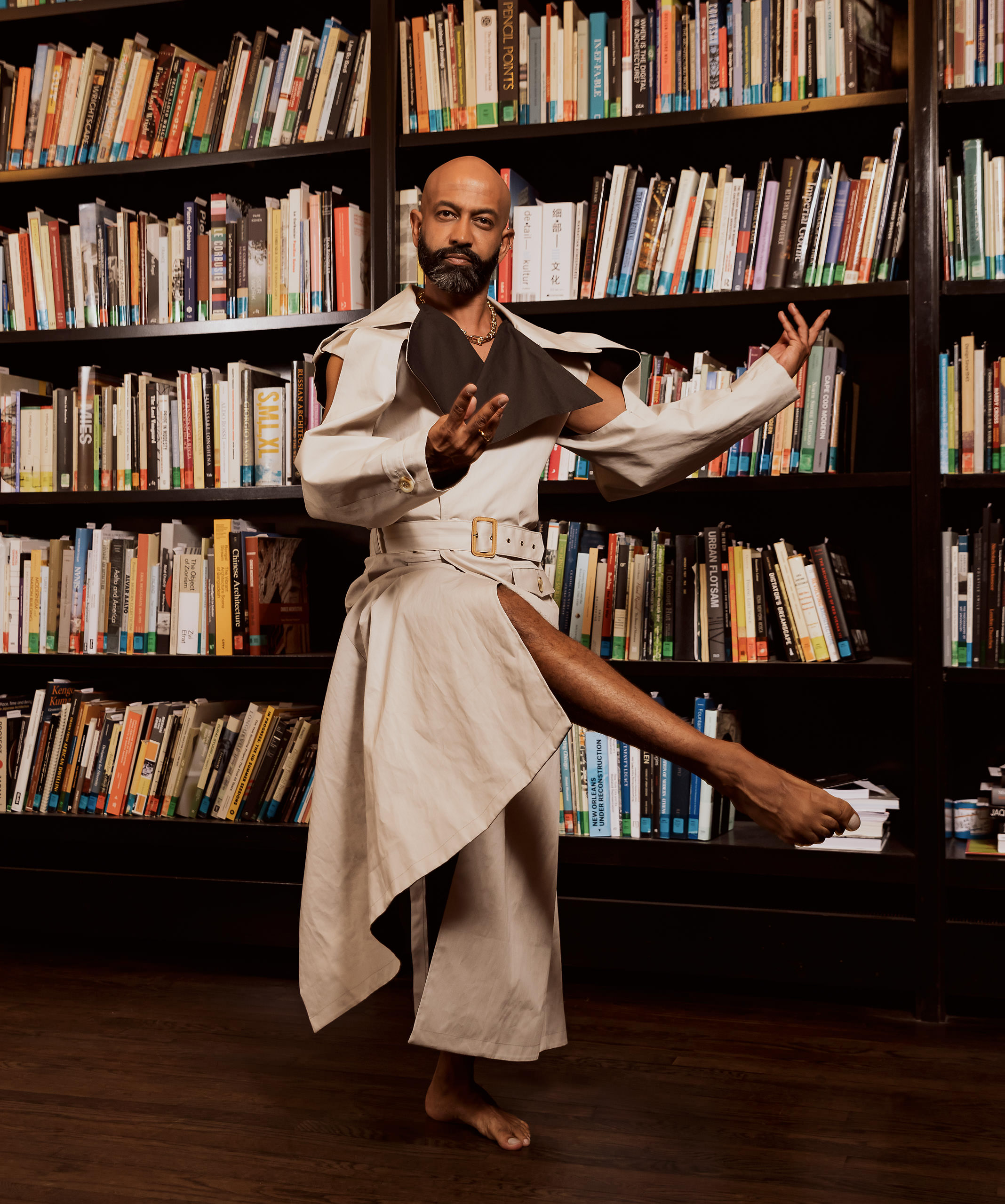

Brendan wears Hogan McLaughlin attire and Tiffany & Co. jewellery throughout.

The Many Identities of Brendan Fernandes

Ballet kink.

_________

Under a haze of pink light, set to a thumping beat from a DJ booth, ballet dancers contort and twist while elaborately tied up bondage-style by shibari rope. Is this ballet? Or something more carnal?

It’s 2019 in the Frank Lloyd Wright–designed rotunda of the Guggenheim, and a crowd mingles about the stage of dancers, watching a strangely erotic performance choreographed by artist Brendan Fernandes. Looking closer, however, one notices the metaphors for oppression being told through movement. The dance piece, aptly called Ballet Kink, examines the push and pull of agency and power through the viscerality of ballet.

Fernandes is interested in power—or rather, he’s interested in the corporeal manifestation of power. Existing in the space between visual art, installation, and dance, his work tells stories of the cultural, gender, and racial structures defined by colonial histories—always, he tells me, with hopeful and forward-thinking connotations. We speak over Zoom, the technology of choice to connect in a COVID world, but the 41-year-old’s globetrotting life is ready to burst through the loosening seams bound by travel restrictions. In fact, he’s leaving for Greece from his home base of Chicago the next day, he shares, for the opening of his commission for the Athens arts nonprofit Neon.

Born in Kenya to a fifth-generation Goan Indian family, Fernandes grew up in a cultural swirl that would later inform his perception of colonial hierarchies and cultural displacement. An affinity for counterculture came after moving at age 10 with his family to Toronto, where he became enamoured with the punk rock scene permeating the multicultural fabric of Kensington Market. It was an affinity that would only be strengthened by the queer club scene he found a home in after moving to New York in his 20s.

Born in Kenya to a fifth-generation Goan Indian family, Brendan Fernandes grew up in a cultural swirl that would later inform his perception of colonial hierarchies and cultural displacement.

“My work is about finding solidarity,” the artist says, now based in Chicago as an artist-in-residence and assistant professor at Northwestern University. “It’s about dismantling power dynamics, breaking down hegemony and Western capitalistic spaces. And within that, I’m trying to find ways that we can think about community.”

To do that through ballet, a medium defined by rigid structures, is a strange yet deliberate choice—one primed by Fernandes’ history with the dance form as a queer person of colour. “I was a little bit too brown for ballet,” he says of his youth spent in training. “In the narratives of ballet, there are these kinds of stories that are very heteronormative: Boy meets girl, girl meets boy, and those characters are always seen as being white bodies. When I was young, I was told, ‘Well, you won’t become a principal because, even if you’re great and one of the best dancers ever, Romeo’s not brown.’ … So the Western structures that I’m trying to break down [in my work] are partially in ballet, and I love ballet, but I still try to find criticality in it.”

Ballet Kink, for example, is an observation on the parallels of power dynamics between ballet and BDSM—two worlds that are hierarchical in vastly different ways. “I’m always trying to talk to my dancers about how do I give you agency, how do I give you the power,” Fernandes says. Comparing BDSM to ballet, he turns to the origins of the latter in European courts as a way to bow to or entertain kings like Louis XIV. “When the court would approach him, they would bow, and the different bows were choreographed for different people,” he explains. “That’s also like a submissive thing, to bow to the king, to give your body to the king.” Even the terminology of ballet—calling teachers “masters”—has echoes of BDSM customs.

It’s this sort of striking imagery—traditional meets countercultural—that has defined Fernandes’ 20-year career, a career that’s seen him exhibit at the Whitney Museum, MOMA, Getty Museum, and National Gallery of Canada among many others. He began ballet training at a young age, but a hamstring injury in his early 20s put to rest his ambitions as a dancer. Yet the yearning for expression endured: shifting instead to visual art, he worked on digging deeper into his complex relationship to identity. “I was physically broken but also mentally and emotionally,” he says of ballet’s intensity. “I took time out away from dance and focused on work about my identity as a Kenyan Indian, looking at the postcolonial histories of trauma and violence.”

One such work, 2008’s Foe, finds him in a performance with an acting coach who teaches him how to speak in an Indian, Kenyan, and Canadian accent. Filmed in an audition tape format, with Fernandes facing the camera and the acting coach speaking to him off screen, he recites a passage from Foe, J.M. Coetzee’s sequel to Robinson Crusoe, in which Friday—the “primitive” character—cannot speak because his tongue was cut out by slavers. As the acting coach directs Fernandes to enunciate more here, roll the r’s more there, the poignancy of the act of an authoritative voice who is not Indian (the coach) teaching Fernandes (who is Indian) how to speak in his own cultural dialect is strengthened by the subject matter of the words he recites.

While the ethos of works like Foe are a foundational basis of Fernandes’ practice, it’s his hybrid dance performances that have led to his renown as a globally recognized artist. He became reacquainted with the form during his enrolment in Whitney Museum’s independent study program, where he studied under dancer Yvonne Rainer. “When she spoke, I was inspired. I started thinking about dance again but never using my body,” he says. “Using other dancers as a way to engage bodies to move together, physically moving in unison. But also, the language of dance is a political space to create momentum.”

It was a time when his relationship to dance was also being informed by the catharsis and community of the New York queer clubbing scene. “I think about the dance floor as a space of agency, a safe space, a brave space,” he says.

Bringing these two concepts together, Fernandes’ work shifted to incorporate both choreographed movement and communal participation: art pieces that blur the lines between protest and party—pieces like 2018’s On Flashing Lights, which lined up a row of police vehicles surrounding a centre stage along Bay Street in Toronto. As the police lights flashed on, DJs from queer and racialized communities performed on stage in a comment on the historical tensions between the two and the validity of what a safe space is and who it is meant to be safe for.

In addition to Hogan McLaughlin attire and Tiffany & Co. jewellery, Brendan also wears Acne Studios jeans and shoes with a Rad Hourani hat.

The piece is a message of community in the wake of contemporary injustices, something also found in Free Fall 49, a series of dance performances and installations in response to Orlando’s Pulse Nightclub shooting in 2016. As dancers perform to the same soundtrack played that night, they collectively fall to the floor 49 times when the music abruptly stops—one time for each victim of the shooting. The power of the series is in the dancers’ resilience in getting back up again after each fall: a through line of Fernandes’ work, which allows space for both mourning and strength.

With community an integral facet of his work, viewers are often invited to join the party—an element that became impossible during COVID measures. But for Fernandes, the restrictions allowed for experimentation with different forms. Earlier this year, B.C.’s Richmond Art Gallery exhibited a two-channel video version of Free Fall. Adding in the medium of film, Fernandes found new dimensions to the work. “My camera people are also dancers,” he says. “They’re moving and choreographed to weave into the bodies.”

Brendan poses with a selection of books at the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Arts, Chicago, Illinois where the entirety of the photoshoot took place.

It wasn’t his only affair with technology in his art. In 2020, Fernandes worked remotely through Zoom by choreographing an entire piece performed via webcam. The piece, titled The Left Space, saw dancers, each in their respective home, interact and reach out to each other on screen through the Zoom grid format. In a time marked by both a global protest movement and a pandemic, the work reimagines methods of gathering and finding solidarity.

To be sure, a pandemic hasn’t slowed Fernandes’ artistic fervour down in the slightest. His experience working through Zoom has invigorated the artist to find new methods of presenting dance while still creating a sense of community. “It’s a different challenge, but I definitely really want to explore more ways of [connecting] dance and technology,” he says, explaining how he sometimes Airdrops graphic cards with dance prompts to random people in public spaces. It’s a tendency toward merging performance art and an unsuspecting public that Fernandes just can’t resist. “These are just ways to find alternative countercultures to support dance,” he says. Art, despite it all, still finds a way.