Daydreamer, Ian McEwan

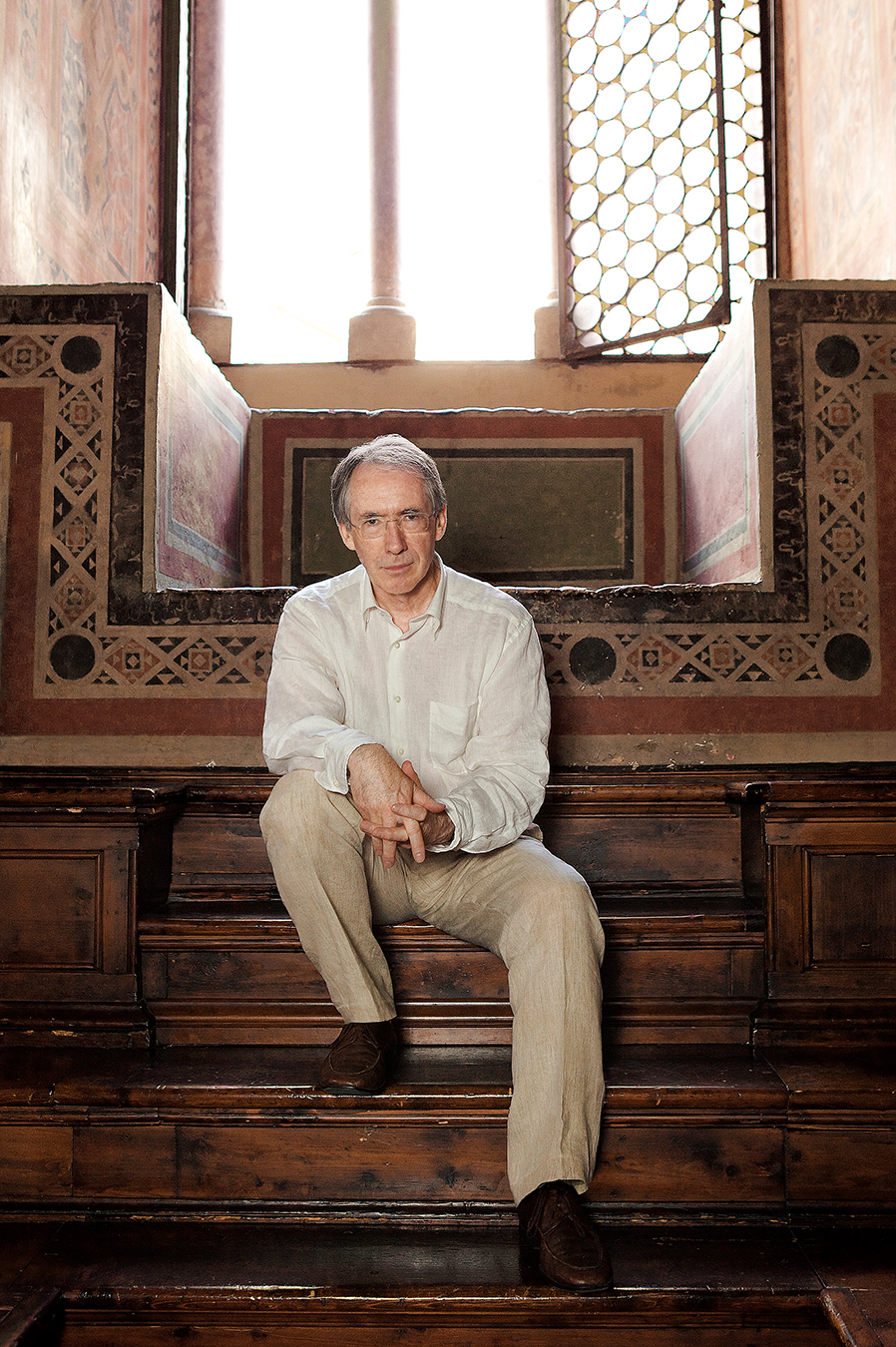

Ian McEwan.

Ian McEwan is lingering over an outdoor breakfast, looking out over the Umbrian countryside near the ancient medieval hill town of Magione. He is sitting on the terrace of a beautiful early-18th-century agriturismo farmhouse, Le Terre di Isa. It’s a hot July morning, and the olive trees and vineyards and sunflower fields are bathed in a humid haze. Ian has already discarded his summer jacket, and sits under a large awning. He is here as a guest of Angela Hewitt’s Trasimeno Music Festival, for a discussion on the subject of classical music in his novels.

Ian is popular now in Italy, but he was unknown here until his children’s book The Daydreamer came out in 1994, recast by his Italian publisher as an adult book—“like a set of Calvino tales,” he says. The book was Ian’s breakthrough success in Italy, knocking even the Pope’s best-seller from its number one perch. (“My blow for secularism,” Ian muses wryly.) The Daydreamer began as a set of bedtime stories for his two sons, 10 and eight years old at the time. One of them, William, is a compulsive daydreamer, just as Ian was as a child. He considers daydreaming an undervalued aspect of mental existence and is convinced that literature depends on it.

Most of us discount our daydreams, forgetting them almost as soon as we’ve snapped out of them. But novelists mark their daydreams so as to remember them and then start to structure them. It is, he says, “where art and ordinary life meet.” He explains that the reason kids as well as adults are discouraged from daydreaming is because “no one can check up on you if you are doing it. It’s one of the few places where the state cannot go. Nobody controls daydreams in Burma or North Korea or Iran or anywhere.” This celebration of a child’s fantasy life has resonance well beyond Italy: Ian gets passionate letters about The Daydreamer from English teachers in American public schools, and on many university campuses it’s become a cult classic.

Adriano, the eight-year-old son of the hosts at Le Terre di Isa, runs over, proudly showing off a green salamander he’s caught in a glass jar. Adriano speaks no English, and Ian little Italian—he struggles to translate, partly to engage this sweet child who’s kept him company during his stay. But it’s also important to Ian, as a novelist, to name things, to name a world both natural and man-made. In this way he is like the late John Updike, a writer he greatly admires as “one of the great namers,” he says. “Too much fiction these days is written in the first-person, about the self, and not sufficiently enjoyed with the world.” His goal is always to “name the world we share and doing it in a way that is quick to the senses.” To that end he is a rigorous researcher. (Darwin’s autobiography is currently on his night table.)

Running through all of McEwan’s novels is a vein of darkness. He is preoccupied by how very thin the veneer of civilization is, how easily it can break down.

But he has other research methods aside from reading, one of which was eloquently demonstrated in Atonement, a novel that has been an extraordinary success. (More than four million copies of the book have sold worldwide and the movie based on it won one Oscar and was nominated for six more.) While writing Atonement, he needed to dress his character Cecilia Tallis for a formal dinner scene early in the novel. He happened to be at a writer’s festival in Hay-on-Wye, and during the question period he began asking his audience (“most of whom were of a certain age”) how he should dress a privileged young woman in 1935. The audience, he said was “fantastically helpful,” giving him “an amazing wardrobe for Cecilia”—as we know from the description of the dresses Cecilia tries on: first a “black crêpe de Chine”, then a “moiré silk dress”, both of which she abandons before deciding finally on “the figure-hugging, dark green bias-cut backless evening gown with a halter neck”. Ian also relies on the advice of his wife, Annalena McAfee, in these matters. “Looking at women’s clothes,” he says, “is part of taking an interest in women’s bodies.”

Does an interest in what his characters wear extend to his own wardrobe? “Not much,” he says, laughing. “I’m one of those people who every three years goes to one shop that sells absolutely everything I need. I just stock up. I can’t bear trying on trousers. I’d rather read instructions about a complicated food digestive… Ah, I hate it. I love the feel of a linen shirt but not enough to leave my study at 11 in the morning and spend a day trying on shirts. But dressing characters—there’s a long tradition in the realist novel of using a detail of clothing as a portal to an aspect of character.”

Ian McEwan was born in 1948 in Aldershot, England, but since his father was a career military officer, Ian spent much of his early childhood abroad, including a long posting in Libya. At 11 years old, he was sent to an English boarding school, Woolverstone Hall, in Suffolk, where he began to write poetry and stories in the school magazine. He obtained an undergraduate degree in English literature from the University of Sussex in 1970 and then did a graduate degree in English literature at the University of East Anglia, where he could submit short stories as part of his MA.

His first two books were short story collections, First Love, Last Rites in 1975 (for which he won the Somerset Maugham Award), and In Between the Sheets in 1978. As a writer in his 20s, Ian’s stories had already been published in some prestigious American and British magazines. These stories, with their lurid themes of pedophilia, incest, and other grim fantasies, attracted attention and gave Ian a reputation as an angry, rather nasty young man, much preoccupied with the darker corners of the erotic world. But writers like Philip Roth and V.S. Pritchett, among others, paid attention to Ian’s disciplined and surgical prose. Following In Between the Sheets came his first novel, The Cement Garden—which also involves incest—in which four children become unhinged after their parents die. Since then, he has written 10 more novels, been short-listed for the Man Booker Prize for Fiction many times, won the Booker for Amsterdam in 1998, and was awarded a CBE in 2000.

Running through all of Ian McEwan’s novels is a vein of darkness. He is preoccupied by how very thin the veneer of civilization is, how easily it can break down. How, in a war zone, all civil society disappears and the ruthless strong man triumphs. He mentions the former Yugoslavia, where an educated civilized people plunged into savagery, turning on their neighbours, with whom they had lived peacefully for generations. He also cites Rwanda and the Sudan, but stresses that we in the West aren’t any different. “Civilization is quite an achievement,” he says. “Eight million people can live within 24 square miles and not tear each other apart, make opera, get along. But what happens when the power goes off or the water runs out?” The fear of how quickly we can fall back into barbarity runs through his novels. He remembers writing The Child in Time, in which a three-year-old child is abducted and disappears forever. Ian was about to become a father for the first time and says he was already inhabiting the fear of the worst thing that could happen to a parent. “Writers take us to the worst place, to see who we are, and how to avoid it, maybe, or just to take us there.” Part of Ian’s world view is to keep an eye on all this, and remind us, as Conrad did, of the chaos just beneath our feet.

And yet, as he grows older, Ian finds himself reaching for a little more optimism. He has just celebrated his 61st birthday, and says he has lost that kind of “reckless pessimism” that he had as a younger writer, with its dark and deliberately shocking visions of violence, obsession, death, and macabre sex, without redemption or, one might say, without atonement. He acknowledges that it’s in the nature of Western intellectual life to be pessimistic about our chances, to assume there’s nothing but an endless decline. “It’s not fashionable to assert that there are more democracies now in the world than there have ever been, or that vast millions have come out of poverty,” he says. “Without being too sentimental or self-deceptive, as I get older, I want the project to succeed.” In preparation for his new novel, which is nearing completion, Ian has spent a lot of time with climate change scientists. And while Ian worries that “we are drifting toward something quite calamitous with climate change,” when he’s with these scientists he sees them “gripped with the possibilities of doing something about it. Liberal arts know-nothings like myself just love the deliciousness of their own pessimism. They don’t think for a moment what they might do about it. It’s all governments failing to do this or Western societies are too this or that. I love the company of scientists. There’s something fundamentally optimistic about science, of feeling that you can know more about the world. We know little but we can know more.”

Still, he’s decided to make the central character of the new novel—working title Solar—a “deeply unsympathetic character”. Ian worries that he will test to the limit our need to identify with, to sympathize with, to love the main character, a climate change scientist. He says ruefully, “Somehow I’ve had to live inside this fat, bloated, self-interested, lying, scheming, thieving character for a couple of years. I think it can be done.” He hopes for as much readers’ forgiveness as was given Updike for his character Rabbit. “Not a nice guy,” asserts Ian, “but the great achievement of the Rabbit tetralogy is that we still want to travel with him. I suppose there’s something fundamentally amusing about Rabbit’s cynical view of the world. Writers have to inhabit other minds, and the best novelists are the ones who can do that. Finding the language to do that, to convince you the reader with just the lines on the page—that’s the heart of it.”

What he’s most enjoyed about his success, he says, is “the freedom to write whatever I like, and I’ve felt I have that freedom for most of my writing life, say from the mid-eighties onwards.” As for the downside? “Sometimes just feeling the pressure of demands. If I didn’t have some little mechanism of guilt in me it wouldn’t be a problem. Quite a lot of obligations—and especially when I’m deeply involved in a novel, it seems as if the whole world is conspiring to stop me. And I have to keep saying to myself, the only reason I’m being asked to do this or that, is because at some point in the past I’ve said no to this or that. And I have to say no and stay home and write now. That’s fine in theory, but I always feel I’m letting good people down.” But then he admits, “That’s not a very serious downside. Literary fame is a very gentle fame. It’s not like football fame, or rock and roll fame, or TV fame, where people are tearing shreds off your trousers. Book people are very civilized.”

“Literary fame is a very gentle fame. It’s not like football fame, or rock and roll fame, or TV fame, where people are tearing shreds off your trousers. Book people are very civilized.”

What has come hard for Ian, with his increasing fame, is learning how to take a compliment. “In my 30s, when people started coming up to me I would be excruciatingly embarrassed—for them, for me,” he says. “I would try to end the conversation as quickly as possible.” Whereas now he’s learned that “when you’ve written something they’ve liked, all you have to do is meet them in the eye and say, ‘Thank you very much.’ ”

Then he adds, with a hint of a wicked gleam in his eye, “I got a nice compliment last night at Angela’s concert. I was in the queue for the lavatory. A guy said, ‘You know, I’ve got your book, I want you to sign it. I think you’re just so fantastic.’ And I said, ‘Thank you very much.’ He went on to say, ‘I just thought Angela’s Ashes was the most brilliant thing.’ I said, ‘Thank you,’ again, and everyone else in the queue started laughing. He said, ‘Why are they laughing?’ and I said, ‘Well, I’m going to have a pee and they’ll explain to you.’ ”

Literary achievements aside, Ian emphasizes his joy in his work as a novelist in “making something, being involved in ongoing interesting work.” This dovetails with “interesting work, deeply satisfying loving relationship with family and friends, good health, adequate income”—Ian’s definition of what constitutes a good life. To this he adds, “Plenty of access to great art, and minor art,” particularly music and literature. “No painting can ever do what music does,” he says provocatively. “A beautiful landscape to walk in. Five hundred to 1,000 words in a day. The company of friends with wine in the evening.” And finally: “To love and be loved,” he says, remembering the Brahms song that Dame Felicity Lott sang the night before in the courtyard of the castle in Magione, with its constant refrain of “Ich bin geliebt, Ich bin geliebt”—I am loved, I am loved.

He reiterates, “It’s such a lucky thing to be loved. People who aren’t, manage, but manage like creatures in the shade.” After a pause, he says, “That’s the baseline of a good life for me.”