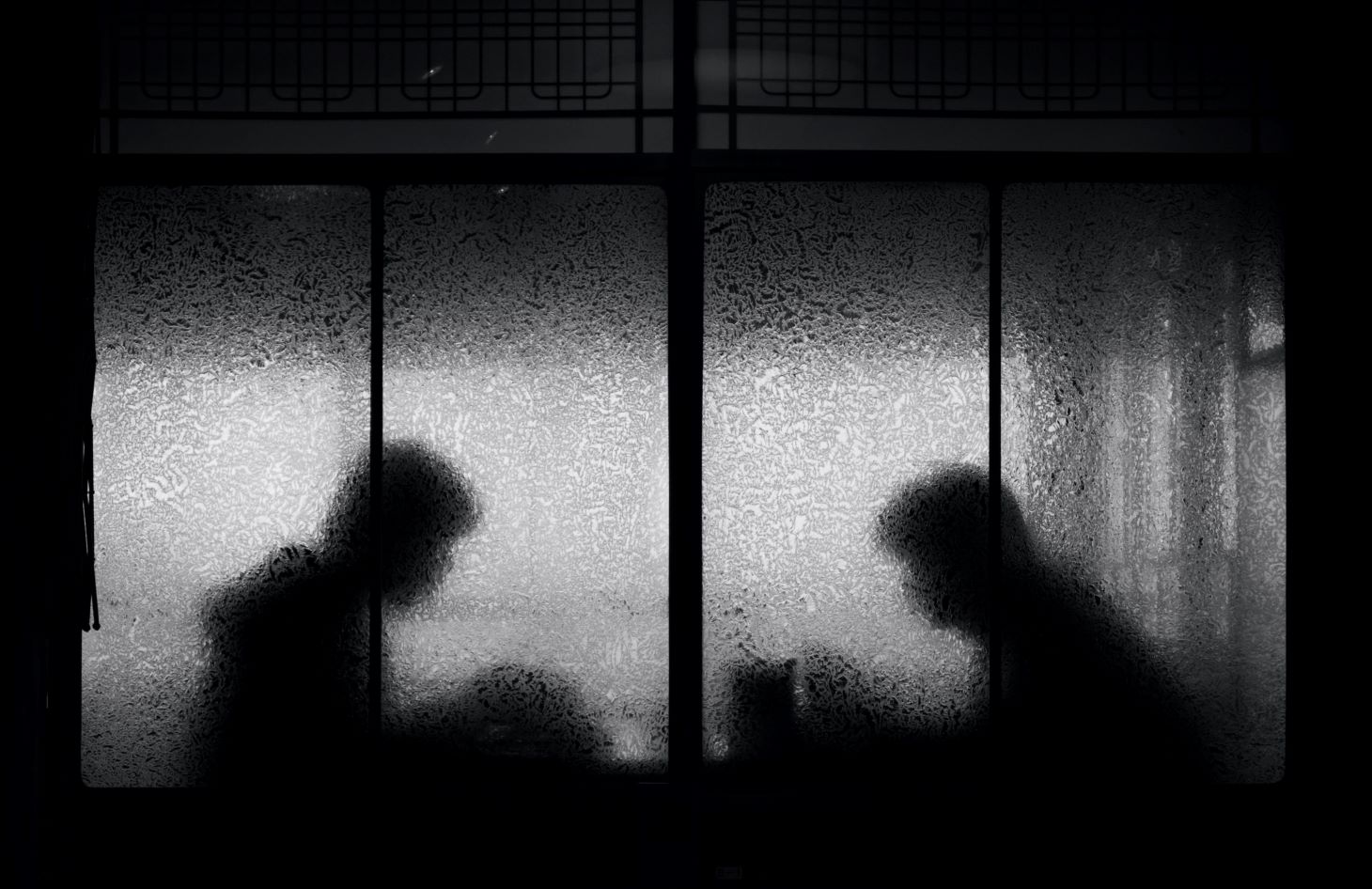

A Kyoto Haze

Around the World in Eight Photographs

Chance meetings.

“The chance which now seems lost may present itself at the last moment,” Jules Verne wrote in Around the World in Eighty Days, which centres on an eccentric Englishman’s grandiose escapade.

In present day London, an eccentric traveller and professional photographer would indulge his young nephew Charlie with stories of his recent travel adventures in uncommon places, such as the Arctic Circle, North Korea, and Afghanistan. Charlie Milner, who grew up surrounded by cameras and hobbyists his whole life, was inspired by his storytelling uncle to take up photography for a living. His profession took him to different corners of the world, framing moments that seem to be aiming not for the imposed settings of a travel postcard but to be a keepsake of the seconds leading up to the photograph or perhaps a reward for attuned timing.

“Photography is strange in a way. There’s an awful lot that we don’t take pictures of, so the ones we do I think say more about ourselves than anything in the photo,” Milner says. “I like the ambiguity around photography—what happened before, what’s going to happen, why this shot, why now. I do necessarily want to answer those in the photo, but I want people to come up with their own stories about what they see.”

One of his favourite photos was taken in Japan. “The silhouette in Kyoto is one of those photos I don’t think I will take again. Everything came together there,” he says. Milner took it on the way down from the Fushimi Inari shrine, a four-hour-long trek through thousands of golden gates. opting for the longer route that offers weary travellers respite from the hike in a small café. “It’s elegantly Japanese—quaint and immaculate attention to detail in the window with stunning views over the city. I remember looking at the menu and glancing up to see two figures on the other side of the glass—anonymous but framed perfectly,” he says.

The stunning black-and-white shot is of one of many intriguing pictures that frame a figure (or only their backside) in the distance, or an object that clearly has a history, evoking the curiosity Milner desires in his work—was this moment premeditated? Or a chance meeting?

There is a calmness to the photographs of Milner’s travels, as if he had been patiently waiting for the exact moment for a while, or the moment was waiting for him. “I’ve taken tens of thousands of photos in my life and only a handful impress me. If the shot is there, trust it to find you.”

Petals on the Pavement. The streets create their own art in Berlin.

As dawn sets. I’m a sucker for old cars. And nowhere does cars and the culture like Japan.

Big Dreams. This young girl stood in the road for a minute or two as downtown Surabaya, Indonesia beckoned. I always wonder about what she was thinking about.

Level-playing field. Coron, The Philippines = The world most beautiful basketball court?

Solitude. Nikiti, Greece – Not too far away from these beaches, thousands of refugees find themselves fighting for a future that has been destroyed through no fault of their own.

In the shadow of Fuji-san. There’s many worst places to more up your boat than Lake Kawaguchiko, Japan… believe me.

Under the cover of a storm. Note to self: A farmer’s shack makes a useful sheltering spot when hiking in Thailand during monsoon season.