-

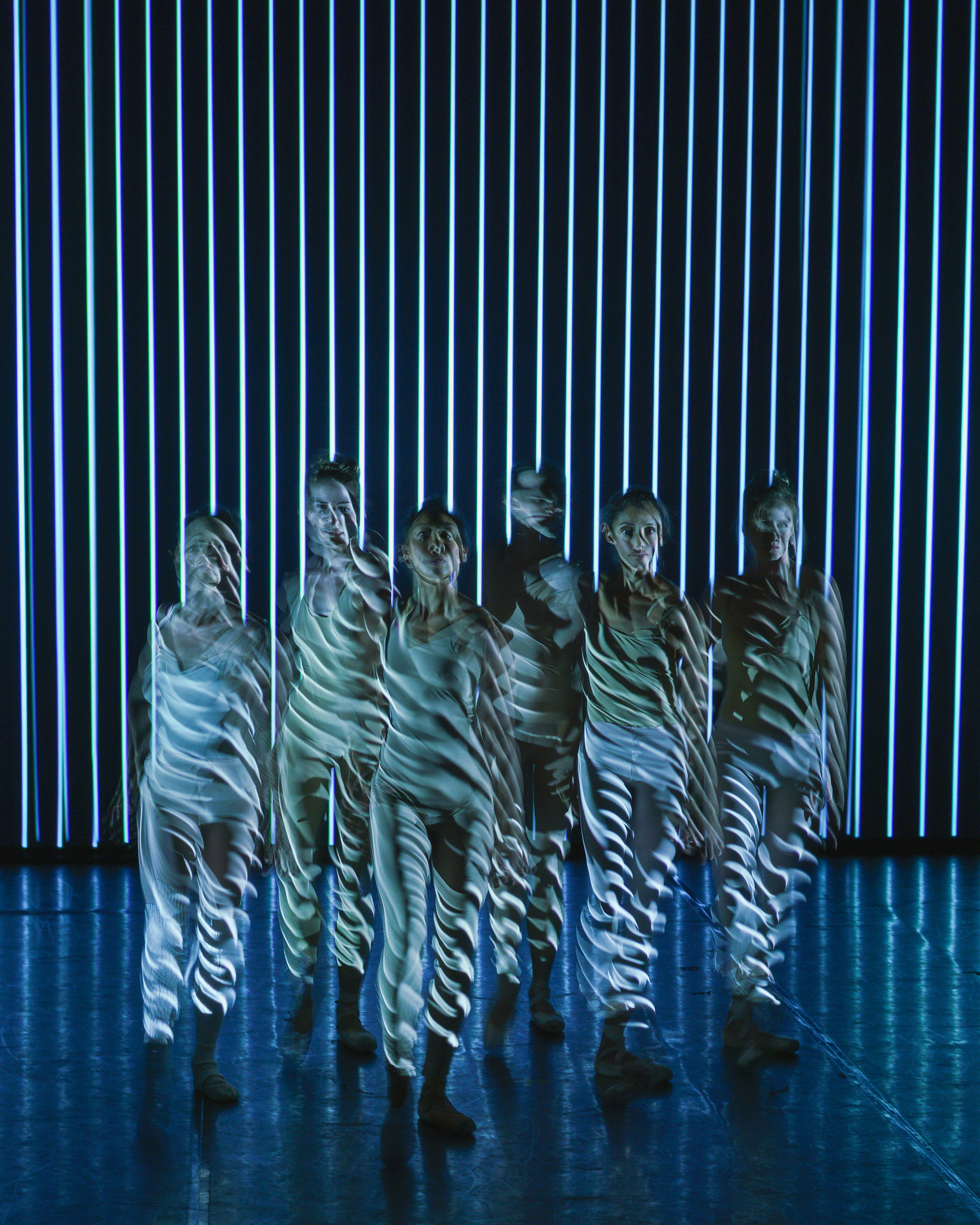

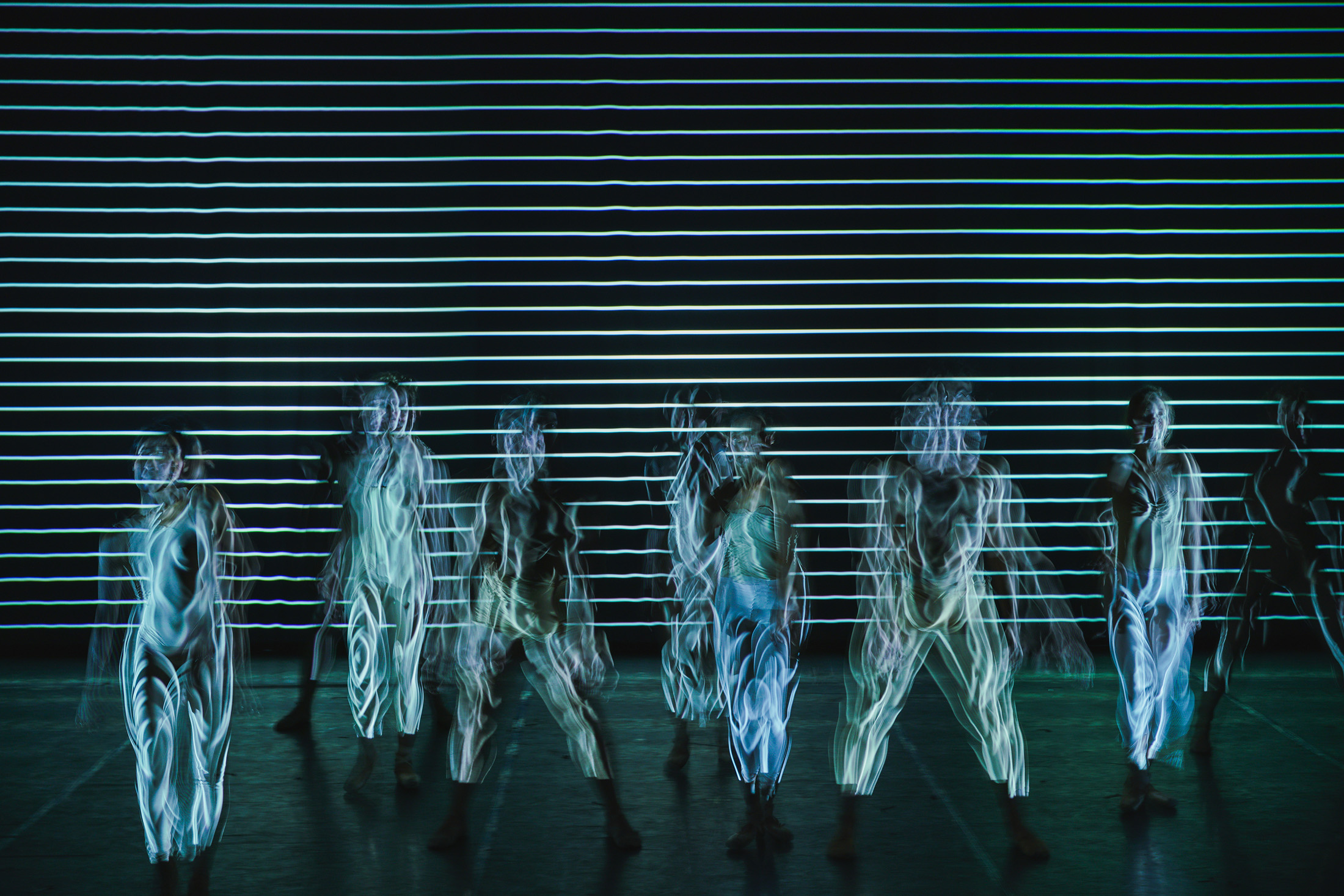

Artists of the ballet in rehearsal. Photo by David Leclerc.

-

Artists of the ballet in rehearsal. Photo by David Leclerc.

-

David Tedaldi in rehearsal. Photo by Elias Djemil-Matassov.

-

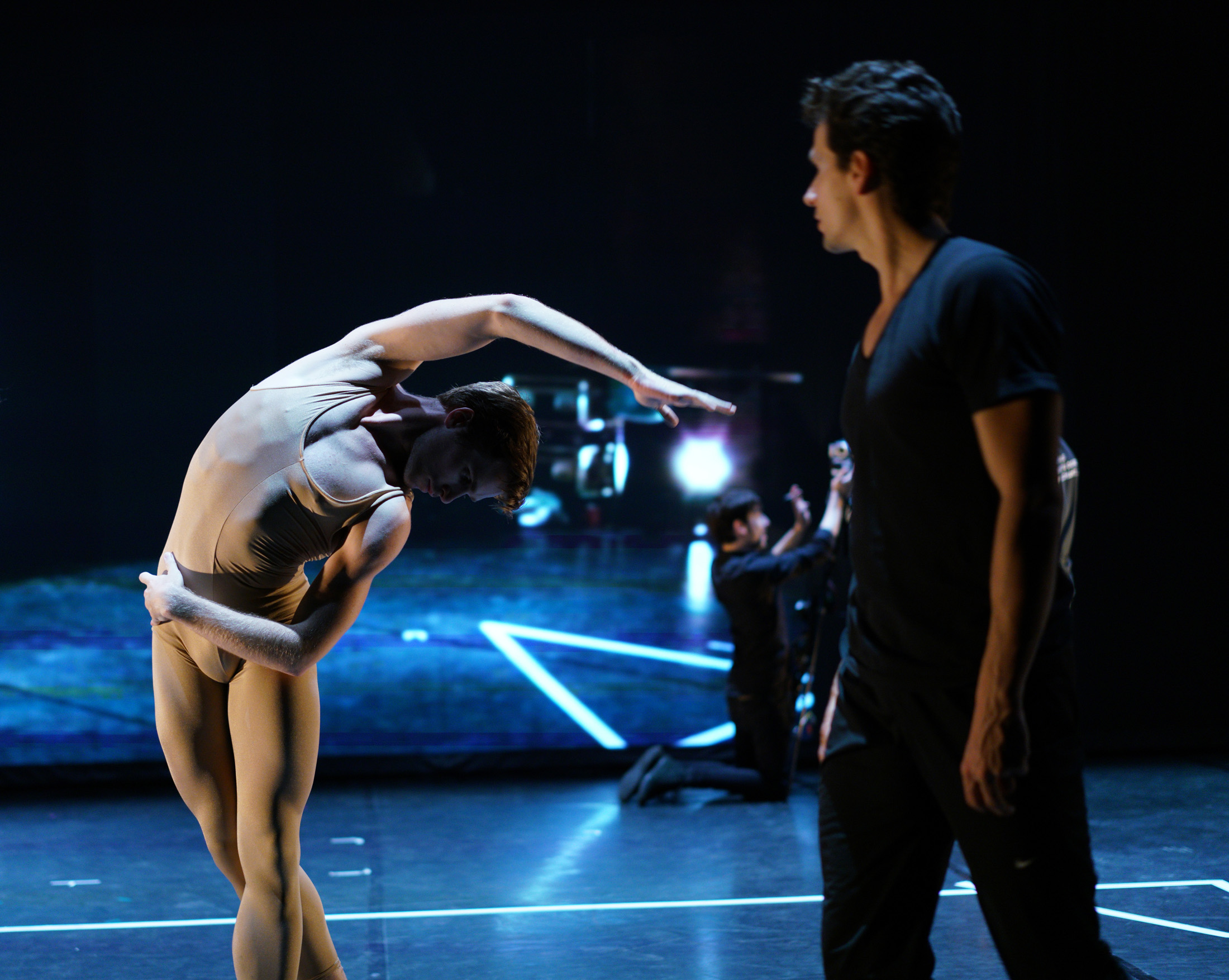

Robert Lepage and Guillaume Côté in rehearsal. Photo by Elias Djemil-Matassov.

-

Greta Hodgkinson and Jack Bertinshaw in rehearsal. Photo by Elias Djemil-Matassov.

-

Harrison James and Guilllaume Côté in rehearsal. Photo by David Leclerc.

-

Artists of the ballet in rehearsal. Photo by David Leclerc.

-

Artists of the ballet in rehearsal. Photo by David Leclerc.

Frame by Frame

The National Ballet of Canada celebrates Norman McLaren.

With the curtain about to rise in Toronto on the world premiere of Frame by Frame, the highly anticipated new ballet masterminded by Canadian theatrical powerhouse Robert Lepage in collaboration with National Ballet of Canada dancer and choreographic associate Guillaume Côté, attention is drawn to the late Norman McLaren, the slight and private Scottish-Canadian filmmaker whose life and work the production celebrates.

“It’s almost a portrait, done in the McLaren style—humorous, quirky, abstract,” says Côté of the work, which merges new technologies with classical dance to simulate animation techniques, including pixilation, pioneered by McLaren during his lifetime. “We combine media in the same way he did, to amplify movement.”

Known for creating works so modern they even once allegedly impressed Pablo Picasso, McLaren, who trained as an artist in his native Glasglow, drew images and sound on celluloid, advancing both the art of animation and the reputation of Canada’s National Film Board where he worked from 1941 until just before his death in 1987 at the age of 72. The recipient of hundreds of awards, including a 1952 Oscar for his anti-war film, Neighbours, McLaren “put his canvas in motion and then made motion his canvas,” as one critic astutely observed.

“It’s almost a portrait, done in the McLaren style—humorous, quirky, abstract,” says Guillaume Côté.

McLaren also made dance his preferred subject matter, using analog technology to lyricize lines and shapes in all his films. Ballet dancers particularly fascinated McLaren, compelling him to celebrate and enhance their artistry in three innovative NFB dance films that helped define the genre—Pas de Deux (1968), Ballet Adagio (1972) and Narcissus (1983), the latter a two-year passion project and the last motion picture made by McLaren before he passed away.

Artistic director of Ex Machina, a multidisciplinary production company headquartered in Quebec City, Lepage knew of McLaren’s dance trilogy going into Frame by Frame and introduced them to Côté and other members of the National Ballet when he first started workshopping the ballet (his first full-length production) in 2015. What Lepage did not know at the time was how integral dance was to McLaren’s identity. McLaren, who was a closeted homosexual, frequently attended dance performances while living in London as a young man. At a 1937 performance of Swan Lake at London’s Covent Garden, he met and fell in love with Guy Glover, an Alberta-raised film producer who was instrumental in getting NFB founder John Grierson to hire McLaren to head up the institution’s fledgling animation department in Ottawa. McLaren and Glover remained together for 50 years.

“We discovered that there was this whole connection and important obsession for McLaren of dance and of course, movement,” says Lepage who includes the Covent Garden scene in his ballet to demonstrate how dance linked the personal and professional spheres of the filmmaker’s life.

Other biographical details include some of the people McLaren worked with both before and after the NFB’s move to Montreal in 1956, among them René Jodoin, who founded the board’s French-language animation division, and Evelyn Lambart, the NFB’s sole female employee who collaborated with McLaren on the 1949 Oscar Peterson short, Begone Dull Care, among other animated film projects.

“We’re more like little cameos,” says principal dancer Greta Hodgkinson who plays Lambart in the piece. “So it’s not really a biography of his life. It’s more to show the importance of the work he did. It’s a completely new experience, a different way of exploring dance and ballet.”

The National Ballet of Canada’s Frame by Frame runs from June 1 to 10.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.