Billy Elliot the Musical at the Stratford Festival

Billy Elliot the Musical opened at the Stratford Festival at the end of May, instantly garnering rave reviews. But the show’s director and choreographer, Donna Feore, didn’t stick around to bask in the glory—she’s preparing a new Broadway-bound show in New York at present and had to fly out immediately following the splashy premiere, missing all the hoopla surrounding her latest hit.

Only recently, on Canada Day, did Feore return to the Stratford, Ontario, home she shares with actor Colm Feore, determined, after a long absence, to take in a show that’s got everyone dancing and smiling as they exit.

“I’m looking forward to seeing it again,” she says, her enthusiasm belying the fatigue built up over a month living out of a suitcase south of the border. “Maybe I can finally enjoy it after all that hard work.” A former dancer turned choreographer who has been directing musical theatre at Stratford for the past 25 seasons, Feore has tackled some big productions in her day. Her resumé includes The Sound of Music, Guys and Dolls, A Chorus Line, Carousel, The Music Man, and last year’s box-office smash, The Rocky Horror Show, among her string of successes.

But none, she says, is bigger than the deceivingly simple Billy Elliot, about a coal miner’s son (here played by 11-year-old British Columbia wunderkind Nolen Dubuc) in Margaret Thatcher’s England who wants to become a ballet dancer. (The show runs until November 3.)

Nolen Dubuc and Donna Feore in rehearsal for Billy Elliot the Musical. Photo by Chris Young.

As Feore describes it, most of the musicals she’s done previously have averaged 14 or 15 transitions, the word given in theatre to describe moving from one scene to another on the stage. But Billy Elliot? “It’s got 32, meaning it’s the biggest show in Stratford history and the most exhausting one I have ever had to direct,” Feore exclaims. Yet, you wouldn’t know to look at it.

Working closely with set designer and frequent Stratford collaborator Michael Gianfrancesco, Feore has made those transitions—including six back-and-forth kitchen and bedroom scenes and eight scenes staged at the village community centre, where young Billy first encounters “bally” as he and his fellow Northerners call it—move as smoothly as the classical dance steps she has choreographed for the show.

Helping to keep the action flowing is a stellar cast of both theatre veterans and novices. It includes a riveting Blythe Wilson as Billy’s dance teacher, Mrs. Wilkinson; Dan Chameroy as Billy’s widowed father; Marion Adler as his addled grandmother; and Scott Beaudin as his angry older brother, Tony.

There are 17 children in this show, among them Emerson Gamble, a National Ballet School student here making his acting and singing debut in the role of Billy’s happily gay friend Michael. “Working with kids is death. They deplete me, I won’t lie,” Feore says. “They ask hard questions I have to answer. But they’re also the greatest joy. I was pretty strict about keeping them children, though. They are 11. I wasn’t going to let any of them look like they’re 35.”

Feore re-imagined the British coal miners strike of 1984–85 as the impending shuttering of the Oshawa, Ontario, automotive plant. Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann.

Feore had the full support of the original creators, who, aware of her reputation for turning any musical she touches into solid gold, gave her carte blanche to do Billy Elliot her way and reinterpret as she wished.

Billy Elliot premiered in 2000 as a Stephen Daldry–directed film with Jamie Bell (recently seen in this year’s Rocketman) in the lead. Featuring a book and lyrics by Lee Hall and music by Elton John, the movie became a play that debuted in London’s West End in 2005. It went on to win four Laurence Olivier Awards, British theatre’s highest honour, including one for Best New Musical. Feore took on Billy Elliot knowing she had to respect its nearly 20-year legacy while, at the same time, making it relevant to today.

“I’m not doing a revival,” she says. “The show needed a modern lens, and I am thankful everyone let me do what I needed to do to make it a show for today. I wanted a raw, visceral feeling.” To get it, she drew on the impending shuttering of the Oshawa, Ontario, automotive plant much like the British coal miners strike of 1984–85, threatens to dismantle an entire town. She also sourced a variety of dance styles, everything from classical and tap to jazz and hip-hop, to tell a story rooted in physical expression.

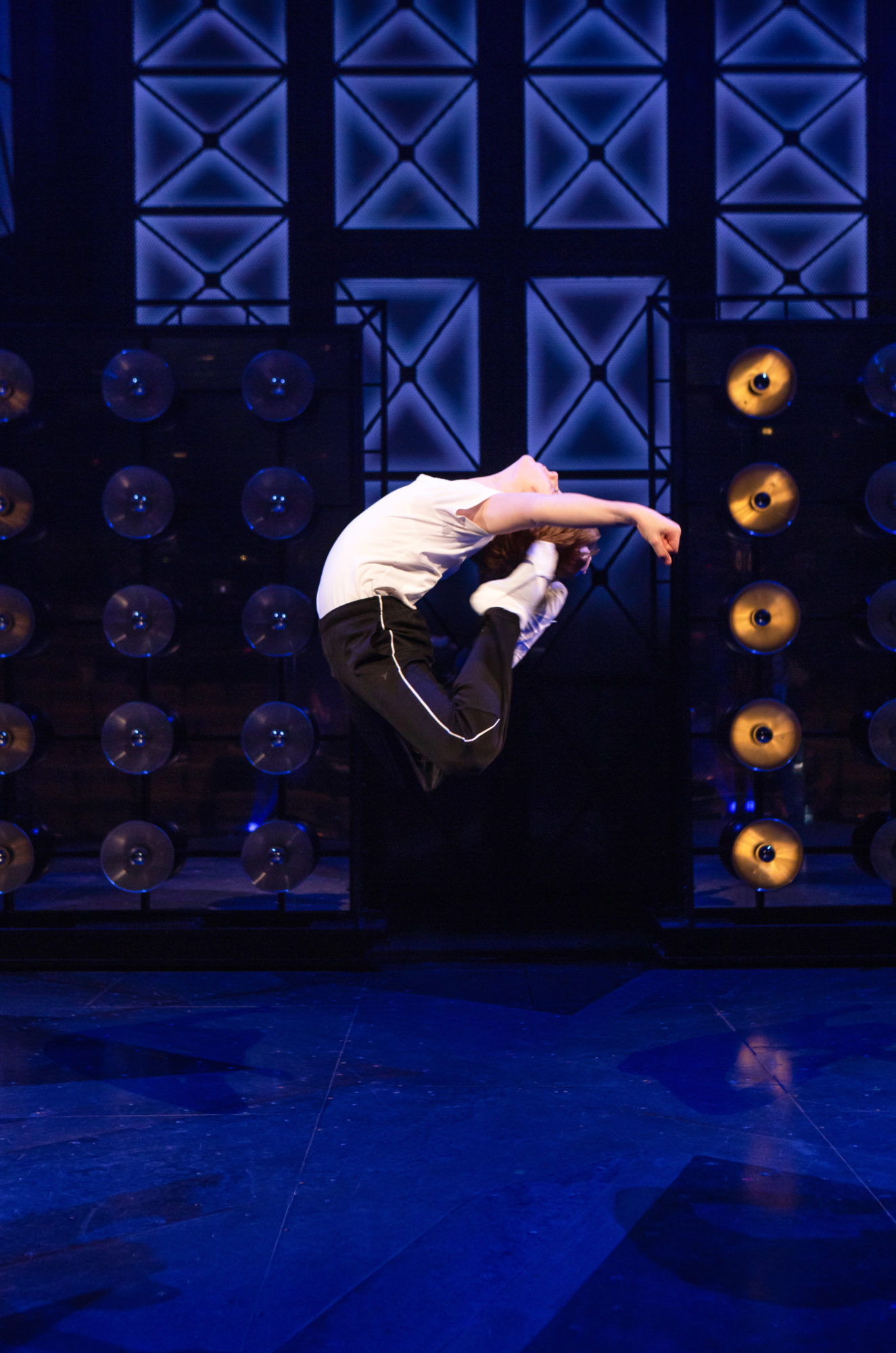

The dance in Billy Elliot doesn’t just entertain. It is a form of escape, not to mention a powerful tool of self-expression. It conveys ideas about belonging, alienation, gender, and cultural identity. But when Billy dances, all he feels is electricity. Feore lets the audience feel it too. “It’s dance within a very strong narrative,” she says. “It’s not dance for dance’s sake. It speaks when you can’t speak anymore. It’s something you just instinctively understand.”

Photo by Cylla von Tiedemann.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.