-

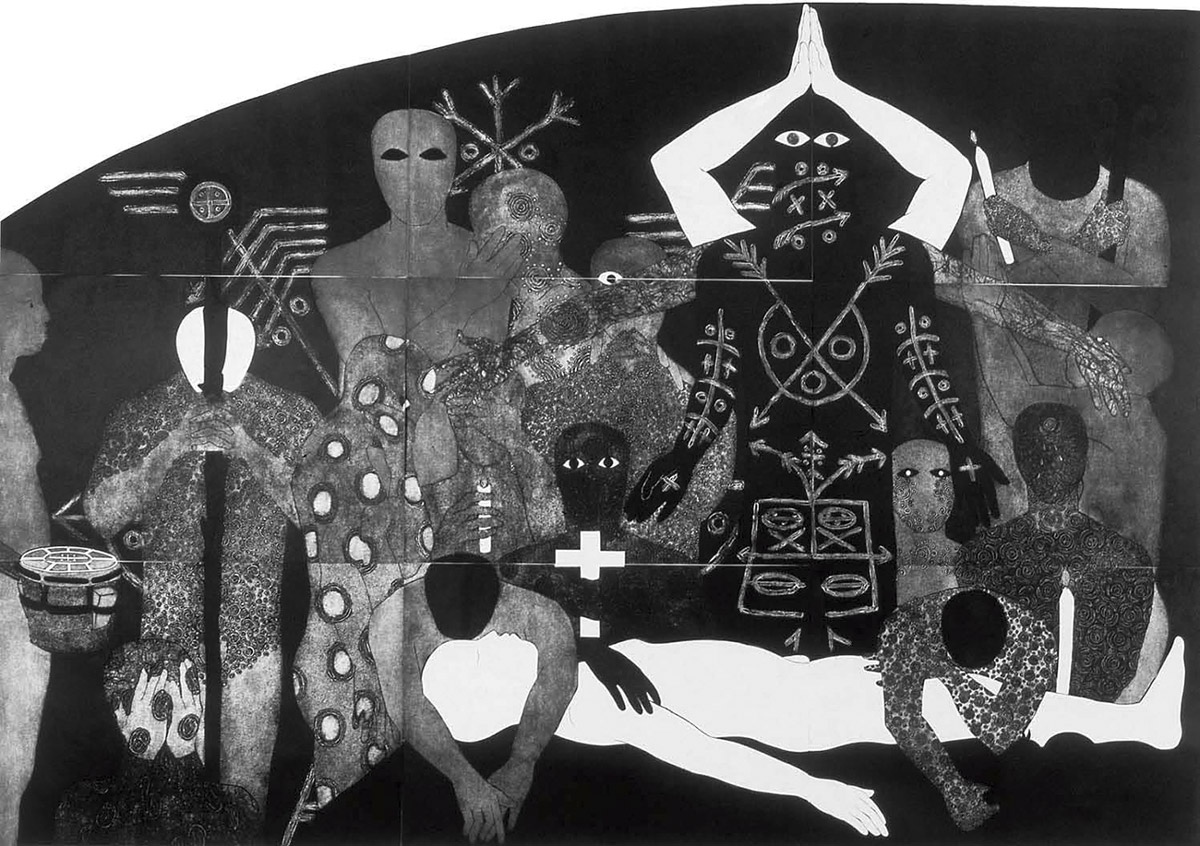

Belkis Ayón Manso, Nlloro, 1991, collography on heavy paper.

-

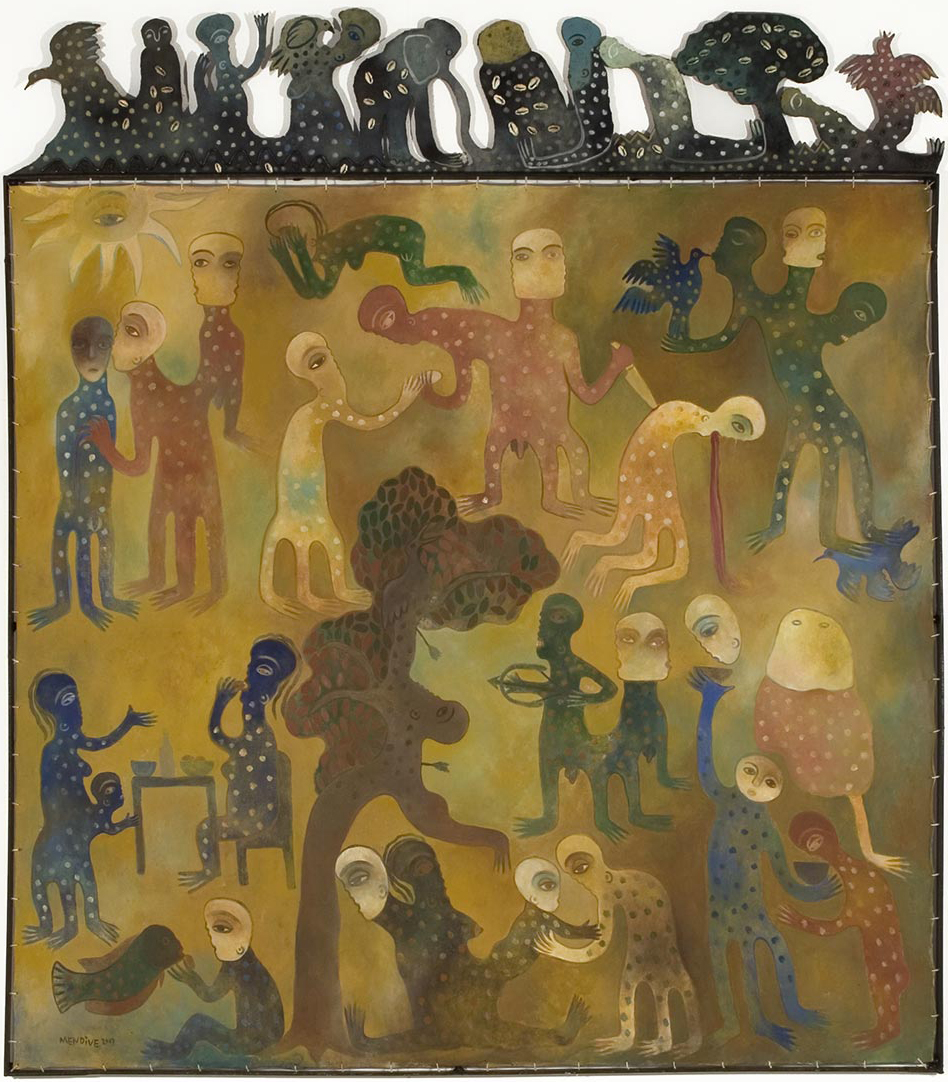

Manuel Mendive, El Ojo de Dios te Mira (The Eye of God is Looking At You), 2007, oil on canvas and painted metalwork with cowrie shells.

-

Santiago Rodríguez Olazabal, El Valor de Las Cosas (The Value of Things), 2009, mixed media on linen.

-

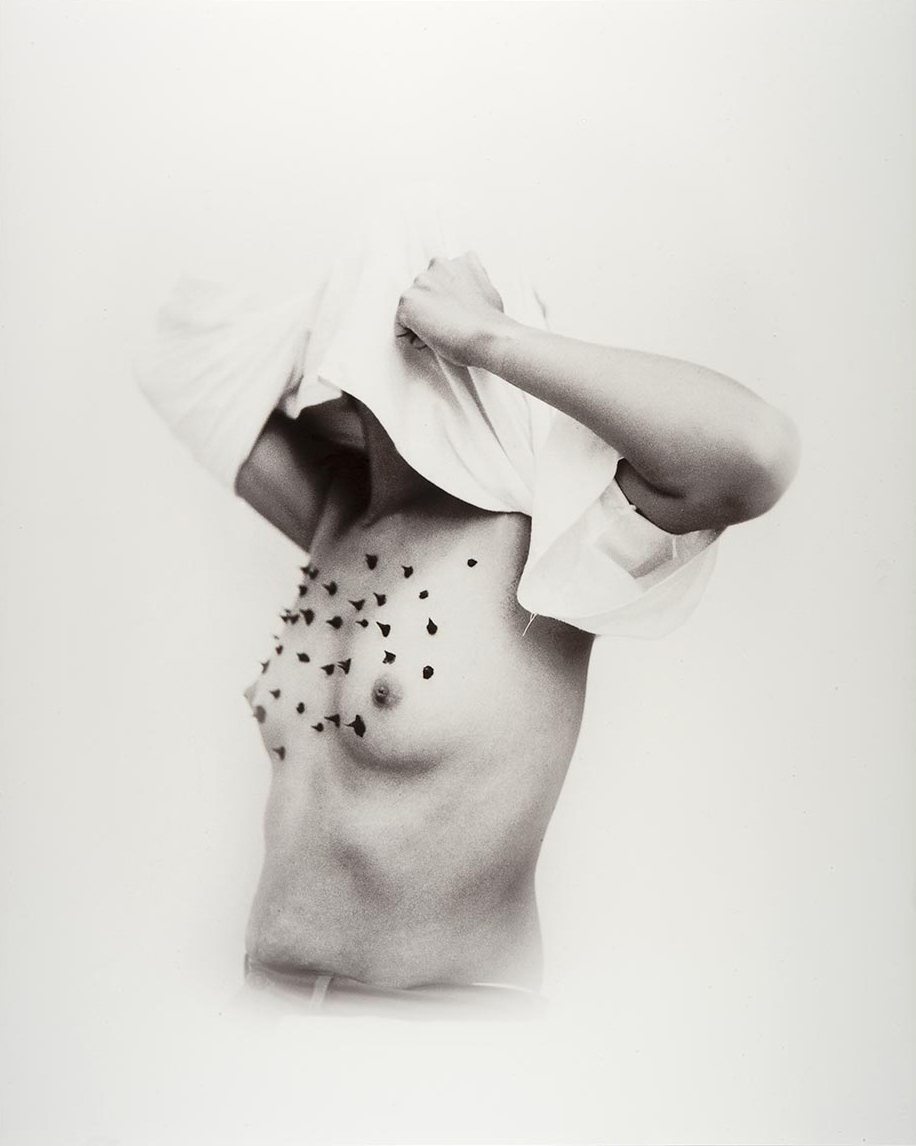

Marta María Pérez Bravo, Protección, (Protection), 1990, photograph.

-

René Peña, White Pillow, 2007, digital print laminated on PVC.

-

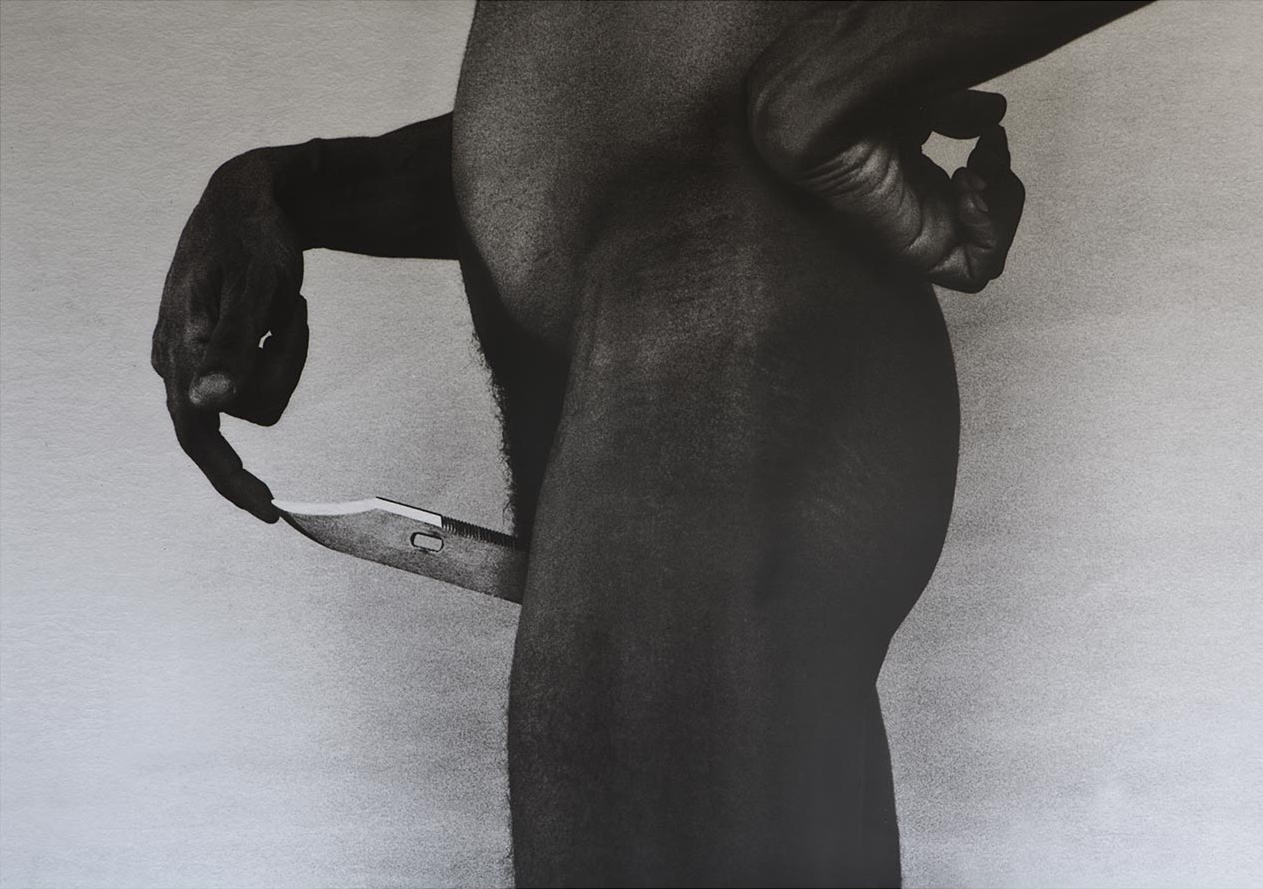

René Peña, Untitled (from “Man Made Materials” series), 1998–2001, digital photograph.

-

Alexandre Arrechea, White Corner, 2006, two video projections on brick walls, eight-minute loop.

-

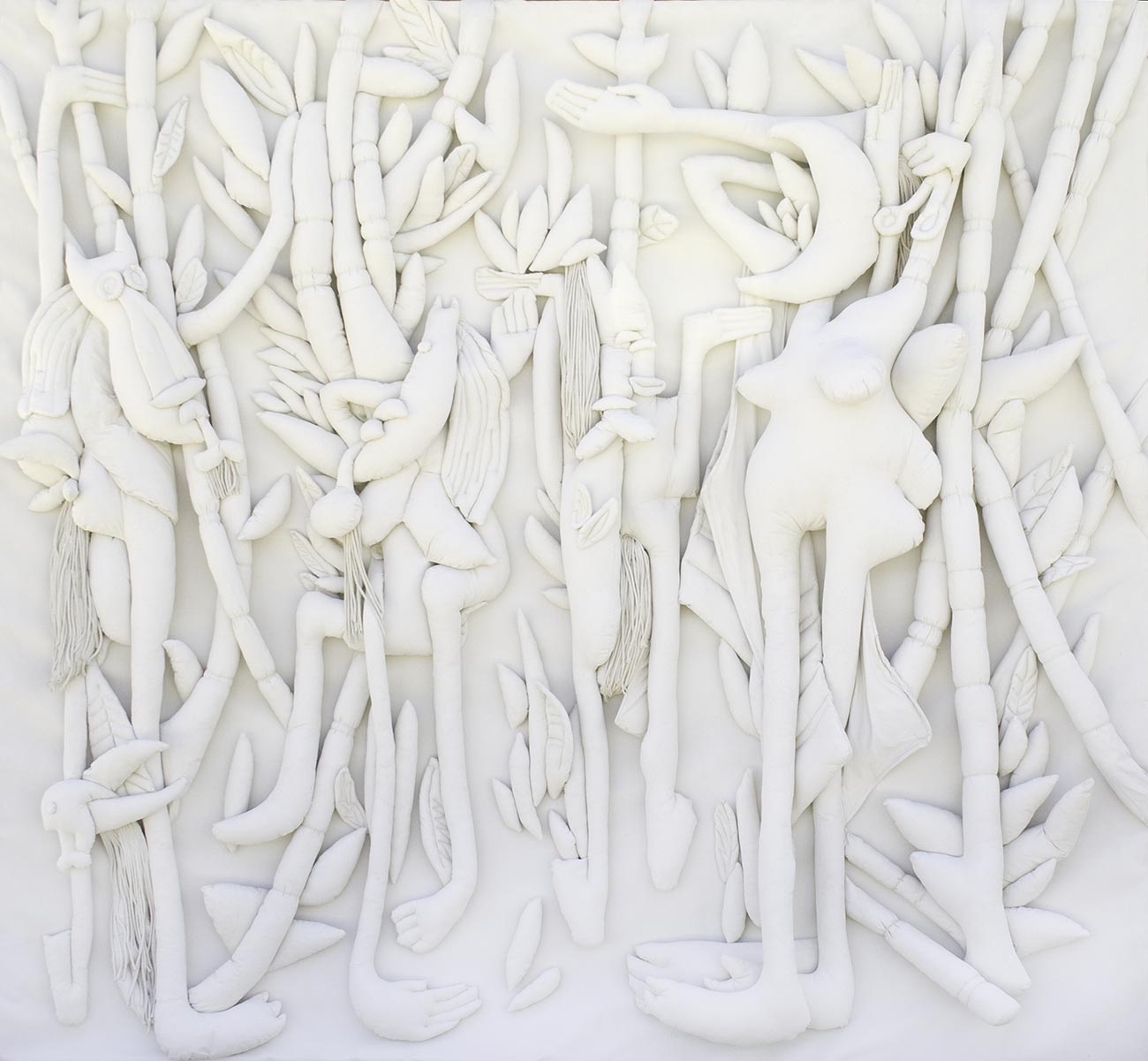

Elio Rodríguez, La Jungla (The Jungle), 2008, soft sculpture on canvas.

-

Alexis Esquivel Bermúdez, Un Paseo Por Parque Lenin Después de La Victoria (A Walk on the Park Lenin After Victory), 2011, acrylic on canvas.

-

José Ángel Vincench Barrera, The Weight of the Words, 2013, four words laminated in 23-carat gold leaf on black acrylic on canvas.

Without Masks

An exhibition of contemporary Afro-Cuban art.

Tonight in Vancouver, a powerful unveiling: Without Masks: Contemporary Afro-Cuban Art at the Museum of Anthropology. The exhibition of 146 artworks dating from 1980 to 2009 brings together 33 contemporary Cuban artists, continuing the museum’s dedication to celebrating a global community through art and artifact. The show is filled with provocative social commentary and engrossing visuals in a variety of mediums, and focuses on two main themes: religion, its influence, and the dedication to African religious practices in Cuba; and racial issues, including the African diaspora and perceptions of the African-origin peoples of Cuba.

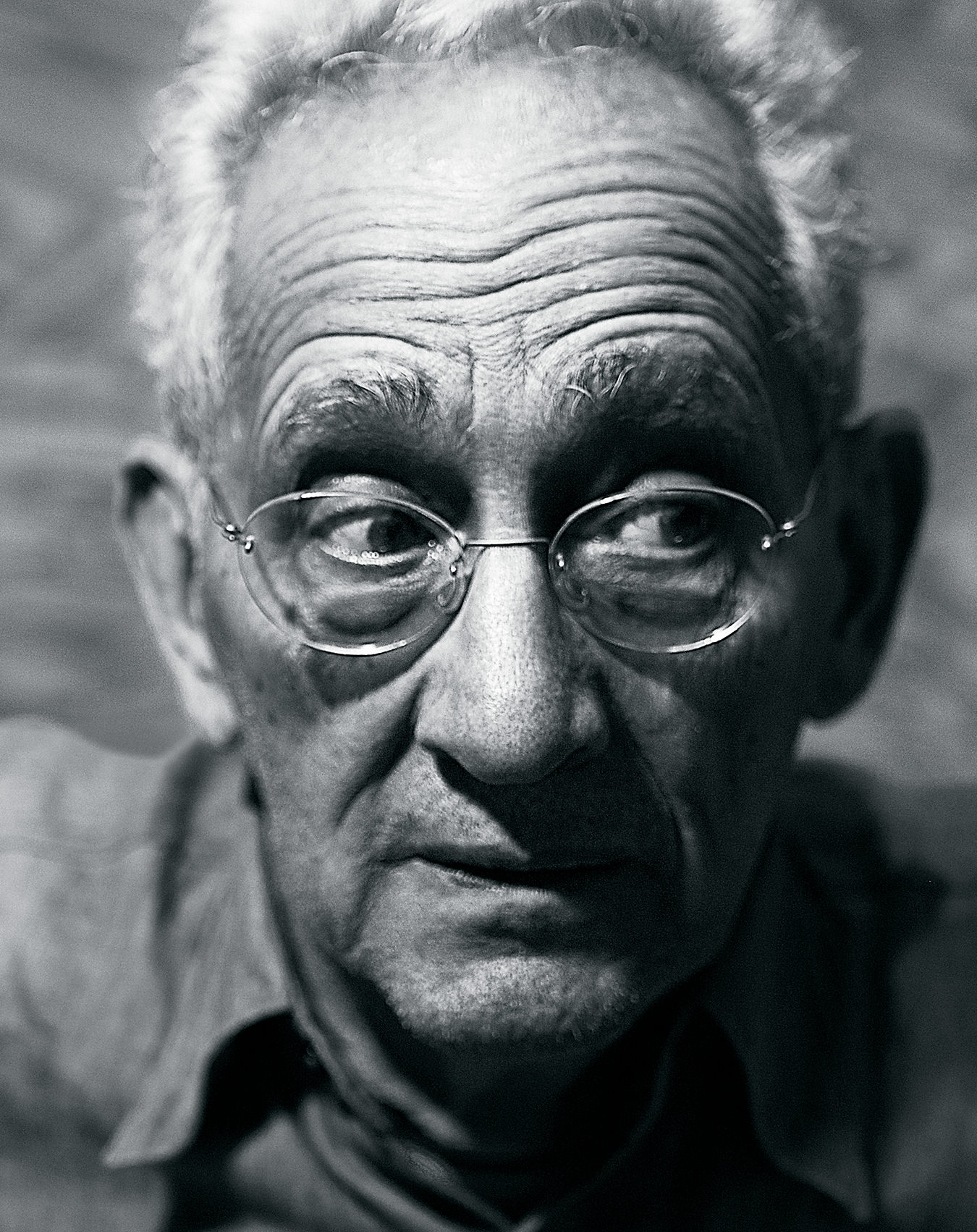

“The order of the exhibit is based on the religious idea of showing the elders respect, so you start with those who have more age, then the younger,” says curator Orlando Hernández. As visitors enter, they will first see the ancestors, deceased artists who are hugely influential in the Cuban arts community and around the world, such as Belkis Ayón Manso. “Each work [here] reflects the different elements of Cubanism,” says Hernández. “We are full of African things even if we have white skin. We all belong to the same kind of root.”

In another room, religious motifs and rituals are explored. As Hernández explains, you can belong to multiple religions at once in Cuba, including Catholicism. “Religion here is not about the mythology though, but about real life, belief at its core,” he says. In this vein, Manuel Mendive’s El Ojo de Dios te Mira (God´s Eye is Looking at You) depicts the ability of each individual to hold his or her own destiny: be it good or evil. Figures have two sides, often with one kissing while the other kills. Santiago Rodríguez Olazabal’s El Valor de Las Cosas (The Value of Things) explores the depth of divination. The mixed media work features shells adhered to a canvas. In a common Cuban practice, one throws the shells (diloggún) to discover which orisha (which loosely translates to “saint”) or parallel being in the other universe is one’s protector.

In another area, Marta María Pérez Bravo documents her artistic explorations through photography, a spiritual offering. She uses her own body exclusively, and explains that while she does not practice religion, she is a believer—the work is her way of connecting to her destiny, and she explains that she works title-first. “I have to find the idea. The work becomes the idea.”

Elsewhere in the museum, Alexis Esquivel Bermúdez’s pop culture-laden works tie contemporary figures (Madonna and Morgan Freeman among them) to pivotal historical events, including Cuba’s involvement in the Angolan War. In another wing, José Ángel Vincench Barrera has outfitted four canvases with slang describing African features, offsetting the crude nature of the words with a deep consideration of his medium—each canvas features a unique blend of black paint, a painterly whisper to individuality.

At its core, Without Masks is a layered cultural experience, and the final product is a rich blend of customs, tradition, and heritage. As is the norm with exhibitions at MOA, it challenges viewers’ perceptions of Cuban heritage, and pays homage to the many ways in which Cuba’s African history has been previously overlooked. Here, the masks come off.