The Elephant Men

Anti-poachers in Hwange National Park.

Until an American dentist sparked global outrage by killing photogenic resident Cecil the lion, Hwange National Park was most famous as home to another iconic African animal, the elephant. Zimbabwe’s largest and oldest game reserve contains some of Africa’s largest herds, estimated by park officials to be as many as 46,000. On a continent ravaged by poaching where every year tens of thousands of elephants are killed to feed Asia’s insatiable demand for ivory, that’s an impressive number, one that should put Hwange on top of every elephant-loving traveller’s bucket list.

But it’s also an unsustainable number, given those elephants’ growing dependence on artificially pumped water during the dry season and the drought-stricken park’s increasing food shortage. A group of men are trying to keep Hwange’s elephants and other wildlife alive in the midst of this looming elephant crisis: a group that includes anti-poachers, ex-poachers turned gamekeepers, and a former provincial wildlife officer turned safari operator who refuses to shut off the water.

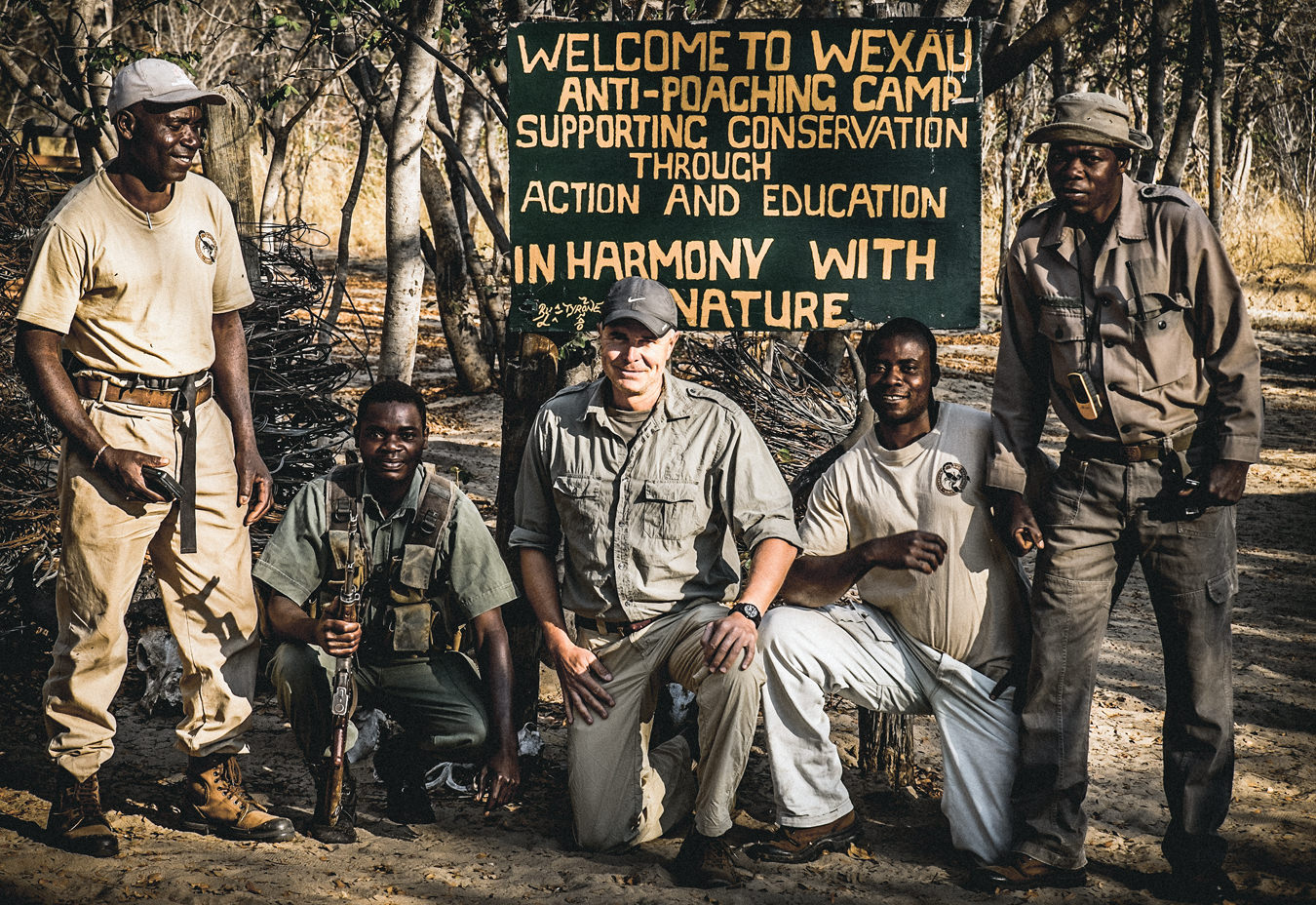

With a click of his AK-47’s bolt, Edwin Ndlovu, a Hwange park ranger locks and loads. Beside him, a tangle of recovered wire snares twists around a wooden post. On this September morning, I join Ndlovu on patrol, along with two members of an anti-poaching squad called the Scorpions. Created six years ago and trained by the International Anti-Poaching Foundation (IAPF), the Scorpions act as additional eyes and ears on the ground, supporting the chronically understaffed Zimbabwe Parks & Wildlife Management Authority, which has fewer than 150 rangers to protect a park nearly half the size of Belgium.

Anti-poachers Collet Ndlovu, Edwin Ndlovu, journalist Mark Sissons, Lenin Ncube, and Bongani Sibanda.

Some members of the Scorpions joined for the money, in a country where jobs are scarce. Others, like Collet Ndlovu, feel compelled to do it. “I love animals very much and I’m proud of what we’re doing, protecting and preserving our wildlife,” he says. Ndlovu means “elephant” in the local Ndebele language, rendering taboo the notion of poaching one, according to Collet. “This was the African peoples’ way of protecting their wildlife in the time before the conservationists,” he explains. “If my name is elephant I’m forbidden to eat elephants. Instead, I am supposed to protect them.”

Fanning out across the bush, we search for crude, noose-like wire snares placed in the path of park animals. Although they can only cover a tiny fraction of Hwange’s nearly 15,000 square kilometres of the Kalahari Sands’ Zambezi teak forests and arid grasslands during their regular eight-hour foot patrols, the Scorpions say they do occasionally catch poachers. Rarely, though, are they ruthless, well-armed soldiers of fortune in dark glasses conducting sophisticated cross-border raids. Since the infamous series of poisonings in 2013 that killed as many as 125 elephants (reportedly the largest massacre of wildlife in southern Africa in the past quarter century), professional poaching has been on the increase here. Most recently, in early October, 40 elephants were found dead by cyanide poisoning. This upswing is mostly attributed to international poaching syndicates turning their attention southward, away from elephant-depleted East Africa.

More often the Scorpions sting desperately poor villagers living on the periphery of Hwange who poach not to sell ivory to the Chinese but to feed their families or make a bit of cash. “We often rely on local leads to arrest villagers who are poaching for meat,” says Scorpion member Bongani Sibanda as we tramp through tinder-dry underbrush, avoiding thorns and dead branches, careful to avoid stepping on lethal snakes like black mambas. Sibanda means “lion” in Ndebele, presumably precluding this anti-poacher from ever switching sides. “Some of my neighbours know we are the real enemies of the poachers, both inside and outside of the park, and they tip us off,” he adds, stopping to note the GPS coordinates of a salt lick sometimes laced with poison by poachers.

The Scorpions act as additional eyes and ears on the ground, supporting the chronically understaffed Zimbabwe Parks & Wildlife Management Authority.

The Scorpions didn’t exist when Solomon “Solo” Sibanda was poaching to feed his family back in 2004. He was caught running snare lines inside the park with another local man, Japhet Mlilo. They were eventually convicted and incarcerated in Bulawayo Prison. “Jail was very, very tough,” recalls Solo one evening by the fire pit at a safari camp deep inside the southwest corner of Hwange called Jozibanini. “There wasn’t enough food, so my family had to bring it.”

Since the infamous series of poisonings in 2013, professional poaching has been on the increase in Hwange National Park.

With us is another ex-poacher, Melusi “Zebra” Ncube, who, after some gentle prodding, recounts how he resorted to snaring animals to survive during Zimbabwe’s post-2000 era of violent land invasions, hyperinflation, and economic apocalypse. Fearing arrest, Ncube escaped and fled Zimbabwe, swimming across the Limpopo River into South Africa like so many of his desperate countrymen. He remained in exile for four years, occasionally working illegally, struggling to send money home to his wife and four children. “It was a hard life and I eventually returned from South Africa and found a job with Mr. Butcher,” Ncube recalls. “He kept me on even after I admitted to having once been a poacher.”

Ironically, Mr. Butcher, the man who arrested Solo and Mlilo and then hired them and Ncube to work for his safari lodges, is also with us tonight. A fifth-generation white African who spent decades as a provincial wildlife officer before starting lodges on communal (tribal) lands in 1995, Mark “Butch” Butcher resembles a character straight out of Hemingway’s The Snows of Kilimanjaro in his khaki shorts, bush shirt, and broad-brimmed safari hat, a .458 Winchester Magnum rifle casually slung over one shoulder. In fact, everything about this wiry, white-mustached dynamo in his mid-50s cries out classic safari hunting guide—except for the funky white Converse high tops and his determination to save Hwange’s elephants, even if it means hiring ex-poachers.

Sensing us, some of those elephants stop slurping and splashing in the cool, fresh water. They stare in our direction, ears flapping, sniffing the air with raised trunks.

As we listen to hysterical hyena laughter, this onetime ranger who might have easily shot Solo, Mlilo, or Ncube explains his rationale for employing them instead: “I was concerned that they were going to go back to poaching and I knew them to be smart guys and hard workers, not gangsters or thugs. Now they all have money to take care of their families without resorting to poaching.” The four of us have come here to inspect Imvelo’s latest camp, three elevated canvas tents overlooking a seasonal watering hole, or pan, near a long-abandoned Jozibanini ranger station.

This is a truly wild place of windblown fossil sand dunes and teak forests, where ancient elephant migration paths serve as roads and animals are still unaccustomed to seeing humans. Butcher says he chose this location because he wanted to re-establish a permanent presence in a long-neglected part of Hwange near where that 2013 mass elephant poisoning happened. He started by re-drilling boreholes to restore the water supplies. “Now park ranger patrols can resupply with water and when they need assistance with diesel or anything else, they can get that from us,” he says.

Opening camps like Jozibanini is part of Butcher’s long-term strategy to combat poaching with tourism in vulnerable areas of Hwange where poachers once operated undetected. It includes employing ex-poachers like Solo, Mlilo, and Ncube, as well as supporting their villages by drilling wells, building schools, and underwriting medical and dental care. Butcher also tries to convince villagers on the periphery of the park that wild animals can ultimately be worth more to them alive than dead—even as park lions and elephants routinely cross the fence to raid their cattle and devour their crops. “Communities surrounding Hwange are beginning to see more benefits from animals remaining alive than from the poachers killing them,” says Butcher. “So when an individual enters the park with the intention of poaching, other community members will say, ‘We don’t want you going into the park to kill because these animals bring tourism to our area.’ ”

For the past 20 years, Mark “Butch” Butcher has been opening Imvelo Safari Lodges in Zimbabwe as part of a long-term strategy to combat poaching with tourism.

In the Jozibanini area, tourism is still so new that the animals scatter at the slightest sight or whiff of us. That’s why I’m surprised to awaken that night and sense a presence just outside my tent. As my eyes adjust to the darkness, the outline of an elephant forms, standing just a few metres away from my tent’s open flap. This spectral goliath remains in place, silently probing the night air with her trunk. I like to think she can smell the difference between poacher and writer.

There are no guarantees of receiving an equally peaceful reception from resident wildlife the next morning as Butcher and I depart from Jozibanini camp on a two-hour mountain bike tour de bush. Banishing thoughts of a hungry lion fatally derailing me, I pedal especially quickly past fresh big cat–paw prints in the dunes. Just beyond camp we pass a diesel pump drawing fresh water for the pan from a deep borehole. It’s one of several that Imvelo’s pump attendants keep running day and night during the dry season to help keep Hwange’s elephants alive. Butcher calls them the park’s true unsung heroes, these young village men who volunteer to live alone out in this unforgiving wilderness, manning the pumps by day, keeping a lookout for poachers, and listening to hungry lions surrounding their tiny tin huts by night.

As my eyes adjust to the darkness, the outline of an elephant forms. I like to think she can smell the difference between poacher and writer.

Imvelo and other safari operators pump water continually during the dry season because Hwange’s elephants will die if they stop. With no major rivers flowing through it and precious little natural ground water, Hwange was a poor location for a national park. Wildlife seasonally migrated in search of water, offering little incentive for people to visit year-round. Then in the 1920s its first warden, Ted Davison, had an idea: drill boreholes throughout the park to draw water for its pans during the dry season. The elephants and other wildlife wouldn’t need to migrate and the park would thrive. “It was not long before the elephants associated the throbbing of the engines with clean water and if, for any reason, the pump was not running and the trough empty, they would stand in a most expectant manner,” wrote Davison in his memoir, Wankie: The Story of a Great Game Reserve.

Fanning out across the bush, we search for crude, noose-like wire snares placed in the path of park animals. ” … these animals are at the absolute end of their tethers,” says Mark Butcher.

Davison’s solution solved Hwange’s water problems and the park and its animals flourished. But over decades his best intentions began to go awry. Elephant populations soared far beyond the park’s natural carrying capacity. Now there isn’t enough food in the park to sustain them. But they remain, with no migration routes that they know about open to them, totally dependent on artificially sustained water. Mass contraception, once thought to be Hwange’s “magic bullet”, has since been discounted as impractical and inhumane. Translocation would require huge logistical resources and massive expenditures while putting elephants into potential jeopardy by moving them to parks that don’t have poaching under control. Mass culling is no longer a socially acceptable option. And letting nature take its course by simply shutting off the water supply, as some Darwinian scientists have recommended, would lead to mass death.

“We created this water problem and now we are morally obliged to sort it out. We can’t just turn off the taps and walk away from it,” Butcher says as we arrive at an Imvelo powered waterhole, one of multiple stops on the pump run, a uniquely hands-on activity open to Imvelo’s more adventurous guests. We’re here to deliver diesel, oil, rations, and pay to his pump attendants. While Solo and Ncube unload diesel fuel we observe a herd of elephants running for the nearby waterhole, alerted, like Davison’s herds of yesteryear, by the sound of our pump.

“I’ve seen people watch these elephants and think it’s wonderful,” says Butcher. What I see is loose flesh hanging off their emaciated bodies, skulls sunken, pelvic bones protruding. Weak from hunger and dehydration, belligerent young bulls swing their tusks at exhausted mothers, forcing them back from the water’s edge. Traumatized elders trumpet, jostling for a chance to drink. Wearied calves fall behind, collapsing from exhaustion. “What they don’t understand,” he adds, “is that these animals are at the absolute end of their tethers.”

Sensing us, some of those elephants stop slurping and splashing in the cool, fresh water. They stare in our direction, ears flapping, sniffing the air with raised trunks. Poaching remains a mortal threat as long as ivory is prized. Conflicts with rising human populations on the periphery of the park are increasing. If the pumps stop running they will surely die. But I’m hoping that these gentle giants may yet survive, partly thanks to the everyday heroism of the elephant men in the heart of Hwange.

Butcher and I depart from Jozibanini camp on a two-hour mountain bike tour de bush.

Learn more about Hwange’s elephant crisis and efforts to conserve them at the Imvelo Elephant Trust.