-

Méristème by Châssi is a giant, globe-like white igloo, designed to illustrate the complex engineering of plants. Montreal, Canada.

-

Cone Garden Bocksili by Livescape is a pop-up garden made of sound-making cones. Seoul, South Korea.

-

Rotunda by Citylaboratory was filled with water to merge sky and earth and left to evolve over time. Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

-

Rotunda by Citylaboratory. Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

-

Secret Orange by Nomad Studio presents the bold colour from different perspectives. New York, United States.

-

Edge Effect by Snøhetta is a steel structure designed to accommodate plants, animals and people. New York, United States and Oslo, Norway.

-

Line Garden by Julia Jamrozik and Coryn Kempster Brantford defines a geometric zone, created by tightly-spaced parallel lines of stretched commercial barrier tape. Ontario, Canada, and Bale, Switzerland.

-

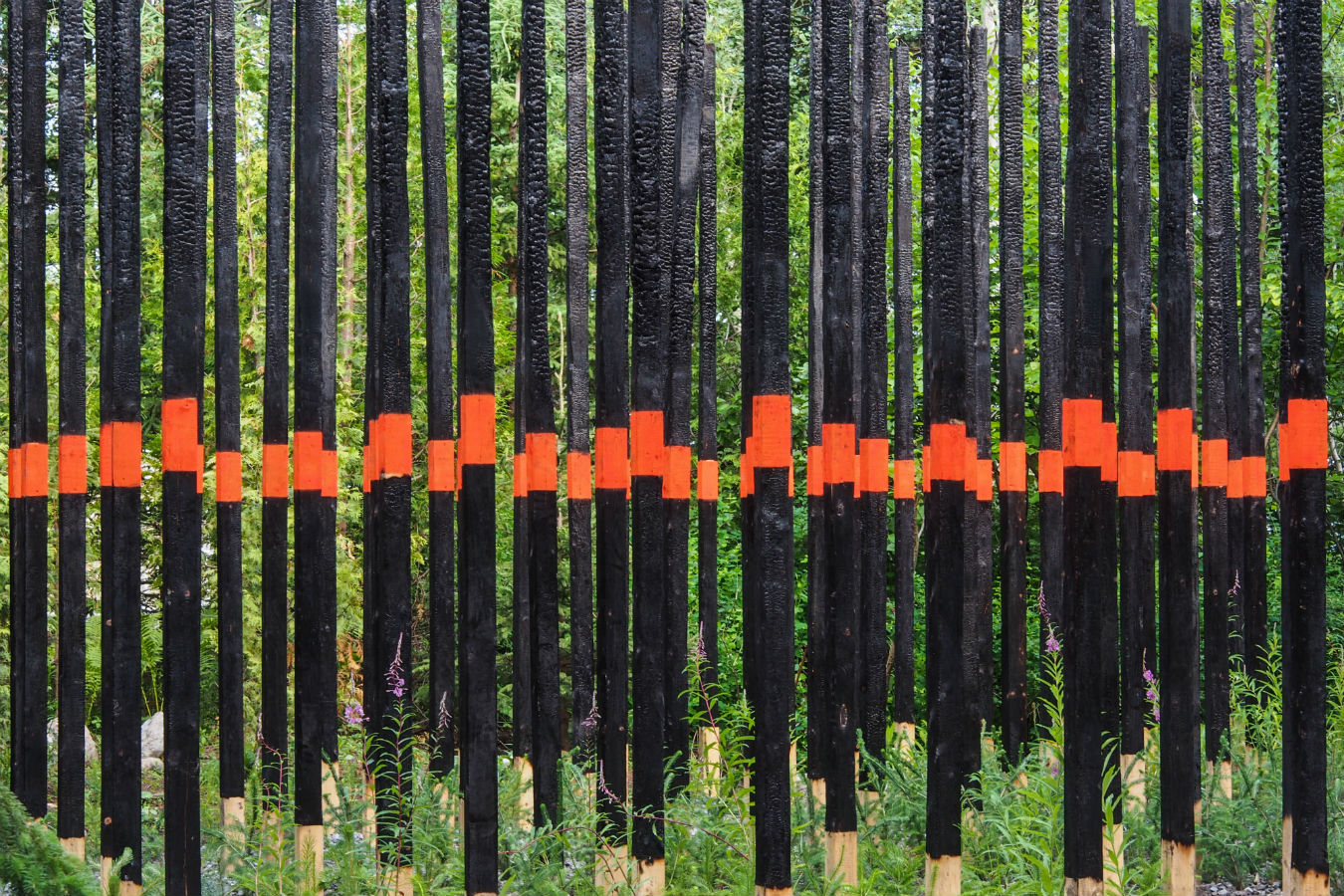

Afterburn by Civilian Projects uses charred posts, ash-rich planting soil, river stone, coniferous saplings, and pioneer herbaceous species to create an encounter with the aftermath of a fictitious boreal forest fire. New York, United States.

Reford Gardens

New ways of seeing.

What was once a fishing camp, situated at the confluence of the Metis and the St. Lawrence rivers in Quebec, is now home to one of Canada’s most imaginative gardens. In 1926, Elsie Reford began converting an estate left to her by her uncle George Stephen, the founder and first president of Canadian Pacific Railway. This was no small feat: Elsie transformed a property of spruce forest into what today is Les Jardins de Métis—also known as Reford Gardens—excavating, building stone walls, moving trees, and even creating compost required to sustain exotic plants in the Quebec climate with leaves she bartered from local farms. Over three decades, she laid out the gardens, supervised their construction, and shaped them into one of the largest collections of flora in its day.

“The garden became very much a career for her,” says Alexander Reford, Elsie’s great-grandson and current director of Reford Gardens. “She was a woman in an era of smart women who, frankly, didn’t have a lot to do other than be active in society and philanthropy. She was engaged in various political, medical, and health areas, but the garden became almost a career. She began it as a relatively mature woman; she was 54 when she started. So it was the second half of her life where it took hold, and over the years, she became very much an expert in her field.” As such, Elsie became very attached to the gardens, and kept them secret and inaccessible; during her lifetime, she only opened them up a few times to raise money for charities during the Second World War.

Following the sale of the grounds by the Reford family to the government of Quebec in 1961, the public was finally able to view the heralded green space, a policy that has remained in place even though the government sold the gardens again in 1994—this is when Alexander saw a chance to become involved in a family legacy as a hands-on director. “It was a last minute effort to preserve the gardens from being developed or destroyed,” he says. The original Estevan Lodge, made from B.C. wood, still stands. George Stephen had spent many summers staying at the lodge and fishing in the river nearby; now, it comprises a museum, dining room, and exhibition space.

The not-so-secret gardens are also home to creative exhibitions, most notably those of the International Garden Festival, which is now in its 15th run. This year, 293 exhibition proposals were submitted for consideration from landscape architects and designers in 35 countries—between five and seven are normally selected each year. “[The festival] was a response to the need for designers to find a space to illustrate their creativity,” Alexander explains. “We took this on as our mission … In 15 years, we’ve produced 150 gardens, and have had over 550 professionals take part in the competition.”

This isn’t your typical garden or flower show, though. “It’s really about contemporary design and landscape architecture,” says Alexander. Each installation site is 200 square metres, and the budget is $25,000, modest by today’s standards. “It’s amazing how much you can do with a bit of creativity and some imagination. A lot of them use materials that are somewhat unusual, and sometimes easy to find and not all that expensive,” he muses. “All of our gardens can be entered—people can touch and climb and do things. Some garden shows are like looking at a painting, you’re standing outside and looking in. Ours are highly-interactive spaces, so you’re looking and you’re touching and you’re smelling, and sometimes you’re part of the installation.”

What excites Alexander about the festival is the designers’ sixth sense. “They have this innate capacity to know what the next future topics are. They work at a different speed, so they pick up on things like climate change, or forestry conservation, or genetically modified plants, sometimes before they become a matter of public concern. The art becomes a venue to present these public policies or issues that are not yet fully digested. They see things more globally, less individually. Using a garden as a vessel of creative expression is something that we marvel at.”