Photo by Sarah Bodri

Stepping Into a Fantastical Papercut Paradise

In Toronto-based artist Winnie Truong's hand-drawn worlds, feminism and foliage are supernaturally entangled.

With sharp lines and careful snips, Toronto artist Winnie Truong builds lush botanical worlds out of paper, one unfurling leaf and quivering tendril at a time. Curious Nature, her solo exhibition at Contemporary Calgary, which runs to August 25, sees her coloured-pencil cut-outs take on a life of their own in fantastical dioramas, a wall mural of pinned wildflowers, three-dimensional sculptures, and looping stop-motion animations set to meditative music.

Assuming the role of a feminist biologist from an imaginary realm, Truong presents her artworks as if they contain curious specimens on display for the purpose of careful academic study. Her dioramas, encased in airbrushed shadowboxes, reveal tiny, otherworldly beings creeping and cavorting through alien landscapes. Each floral or figural element is carved from paper and propped up with miniature balsa-wood supports, so that when viewers walk past them, the figures subtly tremble, in the manner of butterflies impaled by an obsessive lepidopterist.

The rest of the exhibition extends the experience of being immersed in a science-fiction version of a secret garden.

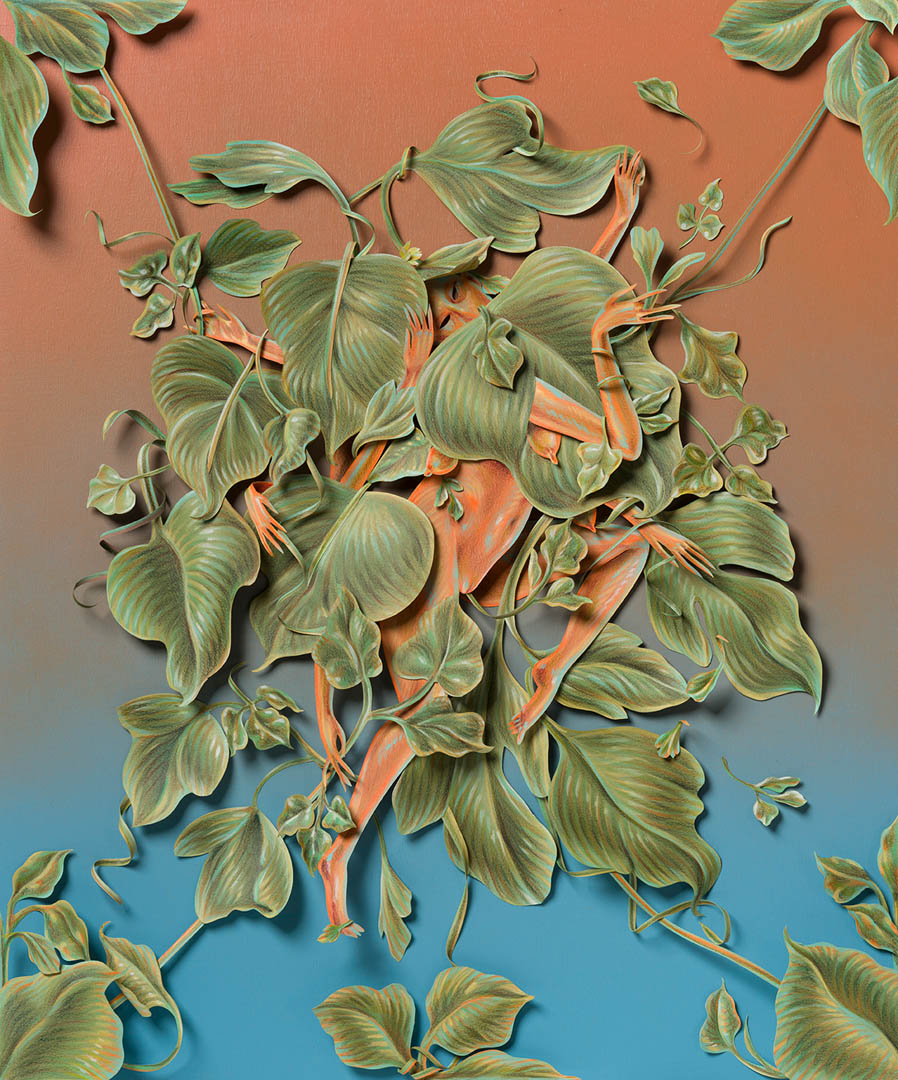

Kudzu Fetters, 2023, Coloured pencil. cut paper collage. 24 x 20 in. 60.96 x 50.80 cm. Courtesy of Patel Brown and the artist.

The Passive Trap

The Passive Trap (detail)

A week before the exhibition’s opening day, I meet with Truong in her Toronto studio, which she shares with painter Kris Knight. It has greenhouse-like windows but only a couple of plants. In real life, she jokes, “I can barely take care of a cactus.” She pulls out a large filing-cabinet drawer filled with black-plastic takeout trays, each containing a handful of pieces from her vast “arsenal of floral bits and bobs.” More than half of her total collection has already been shipped to Calgary for the show.

___

“I try to glean inspiration from the natural environment, but in a weird, twisted way,” she says of the shapes and designs of her cuttings, “where I’m not studying any particular genus or species or native plant life but more the relationships of these plants and how they work within nature through my own imagination.”

Truong’s first foray into making floral paper cut-outs was while she was attending an artist residency in 2016 at Fool’s Paradise, a cottage on the Scarborough Bluffs that was the former home of Canadian landscape painter Doris McCarthy. “When I was there, it was the middle of winter and I was by myself,” Truong recounts. “I was next to the ravine, and there was just so much nature around and little remnants from the garden over the year. I was creating these silhouettes of dried twigs and things out of paper, and I realized: This is the work.” She has been exploring nature, and humanity’s place in it, ever since. “I think that really changed everything,” Truong says of the residency. “I went there knowing that I was going to do something out of my comfort zone.”

Her comfort zone, at the time, was in an enormous nest of hair—or rather, in her depictions of feminized figures being swathed in copious volumes of it. For the first six years of her career, Truong explored hair as her primary theme. On top of being a signifier of class, status, gender, and culture, hair illustrated how beauty can easily tip into grotesquerie when standardized proportions are exaggerated.

Soon after Truong graduated from OCAD University in 2010, she won the 401 Career Launcher Prize, which awards emerging artists with studio space at 401 Richmond, a multistorey arts hub in downtown Toronto. She’s been there ever since, working full-time as an artist thanks to early gallery representation (from the now-shuttered Erin Stump Projects) and grants that provided her with a decent financial berm. Of her career, she cheerfully acknowledges, “It’s been pretty good. I feel like it’s been spiralling upwards.” She has participated in art fairs, residencies, and solo and group exhibitions in North America, Europe, and Asia, and is currently represented by Patel Brown in Toronto and Montreal, and VivianeArt in Calgary.

The art world remained welcoming to her as she navigated her thematic shift. “There was this interim, right before I went into the cut-paper works, where I was creating these all-around environments and character studies with contouring linework, where every strand or mark is wrapping,” she says. She opens the filing cabinet again and pulls out an older drawing, from 2015–16. Titled A Winter’s Burr, it shows a creature whose lavender-blue hair sprouts from her body to fill every nook and cranny of negative space. “You don’t know where she begins and where her environment ends,” Truong says. When she was making works like this one, Truong notes, “I would reach the edge of the frame and see the environment bursting out beyond the seams of what I’d already created. Although I really enjoyed the meditative mark making, there was a point A to point B execution to it that I found was very limiting.”

Hive

Dioramas, with their potential for dimension, depth, and movement, gave Truong “an expanded view of what the potential of drawing is.” Her chosen medium is just as meaningful as her subject matter. “Drawing is a really important starting point for me, as a woman and someone from the Asian diaspora working in Canada,” she says. By plotting a path that meanders around the western canon and its veneration of painting and sculpture, she explains, “I don’t have to dive into that rubric of history in the same way, because drawing has always been relegated to preliminary work,” such as the study or sketch. By deliberately freeing herself from being included in a conversation that she never wanted to take part in anyway, Truong opens up limitless possibilities for making artworks that are dense and layered in concept as well as in style and technique.

In her most recent works, Truong is moving away from just creating landscapes with figures in them and is now “zooming in further,” she says. “I’m obsessed with Karl Blossfeldt photographs,” she tells me, flipping through a book of images by the early 20th-century German artist known for his magnified portraits of plants, flowers, seeds, and leaves. “For me, I’m reading in between the images. To look at something up close is to create something more foreign out of something so familiar. I’m finding faces and returning back to the figure, and imagining these worlds having a life of their own, whether we’re further down the timeline, with the figures dissolving, or whether it’s near the more primordial beginnings, where it starts with faces and limbs and systems that are sentient beings that then give birth to the more formed, robust wimmin figures that you see.”

Truong’s wimmin—she favours the nonstandard, feminist spelling of the word that intentionally excludes men—seem unconcerned by the viewer’s prying eyes. She describes them as “always engaged in their own environment, contorted, and not necessarily performing the most sensual pose. They’re more caught unawares, but they’re also actively doing something in their own world for themselves.” With each slice of her blade into paper, Truong is excising patriarchal influence and imagining what the world might look like without it. Tension exists, but there is no violence. While our individualistic, hero-worshipping society sees dependence as a dirty word, Truong’s fantasy plants and creatures perch and lean on each other to find support and balance.

Sensors

Patterns of Recognition

Twin Letdown, 2021. 24 x 18

The Nervous Creator, 2022. Coloured pencil and cut paper collage, framed. 24 x 18 in. 60.96 x 45.72 cm. Courtesy of Patel Brown and the artist.

It’s perhaps no surprise that Truong is a fan of science fiction. She likes the kind that grapples with “moral and environmental decay,” she says, “and how it largely affects wimmin.” Favourites include television series such as Battlestar Galactica and The Expanse, and books by authors such as N.K. Jemisin, Margaret Atwood, and Octavia E. Butler. In the stories she is drawn to, “the return to nature is what will save us,” she says, as well as “ancestral knowledge of how to take care of Earth and how to provide for ourselves without the technology that will eventually destroy us all.” With her artwork, she says, “I’m creating these new connections of how biology could take place in a realm just outside of our own, and of the different systems: symbiotic, parasitic, or other weird relationships where they weave in and out of limbs and organs and hair.”

From a nearly toppling stack of books, she pulls out two more to show me: the collectible fantasy encyclopedias Codex Seraphinianus (1981) by Luigi Serafini and Man After Man: An Anthropology of the Future (1990) by Dougal Dixon. “My son loves these,” she says, referring to her kindergartner, Arthur. She credits parenthood with allowing her to “reenter a lot of the subjects that I’ve taken for granted, like the vastness of space.” It has also afforded her with a “different kind of efficiency that I didn’t know I had. I feel like that is a parenting trope, but truly, before I had a kid, I’d wake up at 10 a.m., be out the door by 2 p.m., and go to the studio until 7 or 8 p.m. And now I’m so scheduled!”

Within the parameters of real life and its attendant responsibilities, “I can spend infinite time on these,” Truong says of her work. “Until there’s a deadline where I know I have to commit things to glue, there is this infinite feeling of play and pleasure.” In Truong’s imagined herbarium, she collects specimens that are ambiguously primeval and futuristic, natural and otherworldly, and grown in soil untrodden by patriarchal forces, inventing a taxonomy of the kind of world she wants to see flourish. “Every little articulation of a branch or a limb creates a new suggestion or narrative,” she says. “I’m nowhere near beginning to exhaust the worlds I’m building.”

Field Notes, Meadow II, installation view, Varley Art Gallery of Markham, 2023. Photo by Toni Hafkensheid.