Performance Artist Miles Greenberg’s Physical and Mental Explorations

Sculpting the weight of moments.

Miles Greenberg could be called a sculptor. But rather than marble, the performance artist sculpts with flesh and time, moulding moments with the body that unfold almost imperceptibly over long stretches of time. “There are things that the body can communicate very effectively in a certain context,” the Montreal-born artist explains to me from his apartment in New York, casually peeling an orange as he speaks. “I have developed a whole language around it for myself.”

This language is inflected by corporeal potential and limitations in relationship with the transient nature of time. Exploring the edges of his own mental and physical capacity, Greenberg’s work is known for stoicism in the face of extreme—and yet monotonous—circumstances. In 2019’s Haemotherapy (I), he stands still for hours as a continuous drip of water splashes into a glass container balanced on top of his head. Cornstarch falls from the ceiling and glides almost seductively down his body for seven hours until he is enveloped in Pneumotherapy (II). For 2020’s Oysterknife, he walks on a conveyor belt for 24 hours straight, blurring the lines between ecstasy and exhaustion.

Miles Greenberg prepares for his work Admiration Is the Furthest Thing From Understanding (2021) at the Bangkok Art Biennale.

Greenberg is less interested in the pain factor of his work and strives to clear a misconception that the nature of his type of performance art is simply about suffering or masochism. “What I’ve learned in my private life, and from my work, is that life isn’t really about that [pain] either. I think that when I’m performing, the pain becomes very incidental to something a lot bigger and a lot more profound.” The core of his performance is in the act of discovery—what he reveals through himself under the weight of time.

A protegé of Marina Abramović, Greenberg began performing as a teenager and gained rapid traction in the art world. Now, at 24, he’s completed residencies at École International de Théatre Jacques Lecoq and Palais de Tokyo in Paris, the Red Gate Gallery in Beijing, and the Watermill Center on Long Island. He refers to his relationship with performance as one born out of necessity.

“I always wanted to be a sculptor, but I didn’t have access to the means by which I could make the kind of sculpture that I actually wanted to make. I wasn’t really interested in things that I could do with my own two hands,” he says. “I had this obsession with monumentality. And I think that performance was an elegant solution to a total lack of material resources. It’s also a nice mantra to carry with me, because performance always comes back to this idea that you have everything you need.”

This intimate understanding of his physicality feeds into Greenberg’s own artistic exploration of his identity, his existence in a Black and queer body, and how that relates to his relationship with the outside world. Extending this element of personal reflection, he chooses only Black performers when including multiple bodies in his work—as he did in Late October (2020), which featured six other performers alongside Greenberg, their nude bodies painted jet black and eyes glazed with white contact lenses, slowly rotating for seven hours straight.

Greenberg’s work should not be viewed as a reduction to a commentary on race. He uses race only as a tool, he says, to illustrate the universal themes of his work: love, heartbreak, sex, poetry. It’s a distinction he finds he has to make often in the art world: that just because he is Black does not obligate him to create race-specific works.

“I think any young Black artist immediately confronted with the art world as it is has this predicament of, ‘Well, [race] is the only thing I can talk about. My lens can’t communicate anything but this incidental nature of my body.’ I got bored, because I realized that what I wanted to communicate in my art—the reason I became an artist—was things that I felt were universal. If I had spent my entire life up until that moment looking at images of white bodies in classical painting, classical sculpture, and in contemporary works that were executing universal ideas, and I made the translation onto my body, then people could do the inverse as well,” he says of his decision to use only Black bodies in his work.

_________

“I approach my whole life in rituals, and I think that finds its truest form in my work.” —Miles Greenberg

It seems fitting that Greenberg’s most recent work finds the artist engaging in plastic arts for the first time, considering his initial love affair with sculpting. The project, a sculpted iteration of Late October, literally solidifies movement: he used 3D scans of his slowly rotating body to design a figure captured in every stage of action, which were then used to create a mould for large-scale sculptures. The figures, exhibited at Arsenal Contemporary Art Toronto last year, unfurl themselves like physical timestamps of movement, a precise marriage of performance and sculpture. It’s his first foray into visual art, and it won’t be his last, he tells me, with determined enthusiasm. “I think that this is who I am now,” he laughs. “I am very happy with the symbiotic relationship between the two [visual art and performance art].”

Greenberg’s affinity for the arts is thanks in large part to his unique childhood: he grew up amongst a Russian absurdist theatre troupe, where his mother, an actress, was a member. “My earliest memories are not being in daycare but instead being on tour with the troupe. I really grew up around, like, clowns,” he says. But he states that he doesn’t consider his own work to be theatre or drama. While narrative forms require arcs and structure, Greenberg’s performances are moments suspended and unfolded in minute scales.

The iteration of Late October that premiered at Arsenal in Toronto uses 3D scans of Greenberg’s body as sculpture. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy of Miles Greenberg.

Lepidopterophobia (2020), for instance, saw Greenberg locked in a Perspex box filled with atlas moths and owl butterflies for five hours. The title references the artist’s own phobia of moths, adding an intimate dimension to the work. The performance, which was recorded and uploaded to YouTube in its entirety, can be dipped in and out of at any point—each frame, second, or hour exists on its own. “You’re not meant to watch any of my stuff from beginning to end. Because there is no beginning and there is no end. I am very insistent with galleries and spaces that I work with that there’s no moment of applause,” he says. “I need to work in circles, not lines. I don’t really like the pressure that it puts on me to create something that people are to watch from point A to point B. Somehow it feels very vehicular. I would rather just have something that’s consistently generative on itself, durational, and with enough room for a bit of serendipity to come in and write the script for me.”

That element of serendipity is underscored by a sense of unpredictability of how things will unfold, even for the artist himself. “I don’t know whether or not any of my performances are going to work before, because I don’t rehearse,” he says, adding, “I find it a lot more interesting to be an unprepared person walking into these situations.”

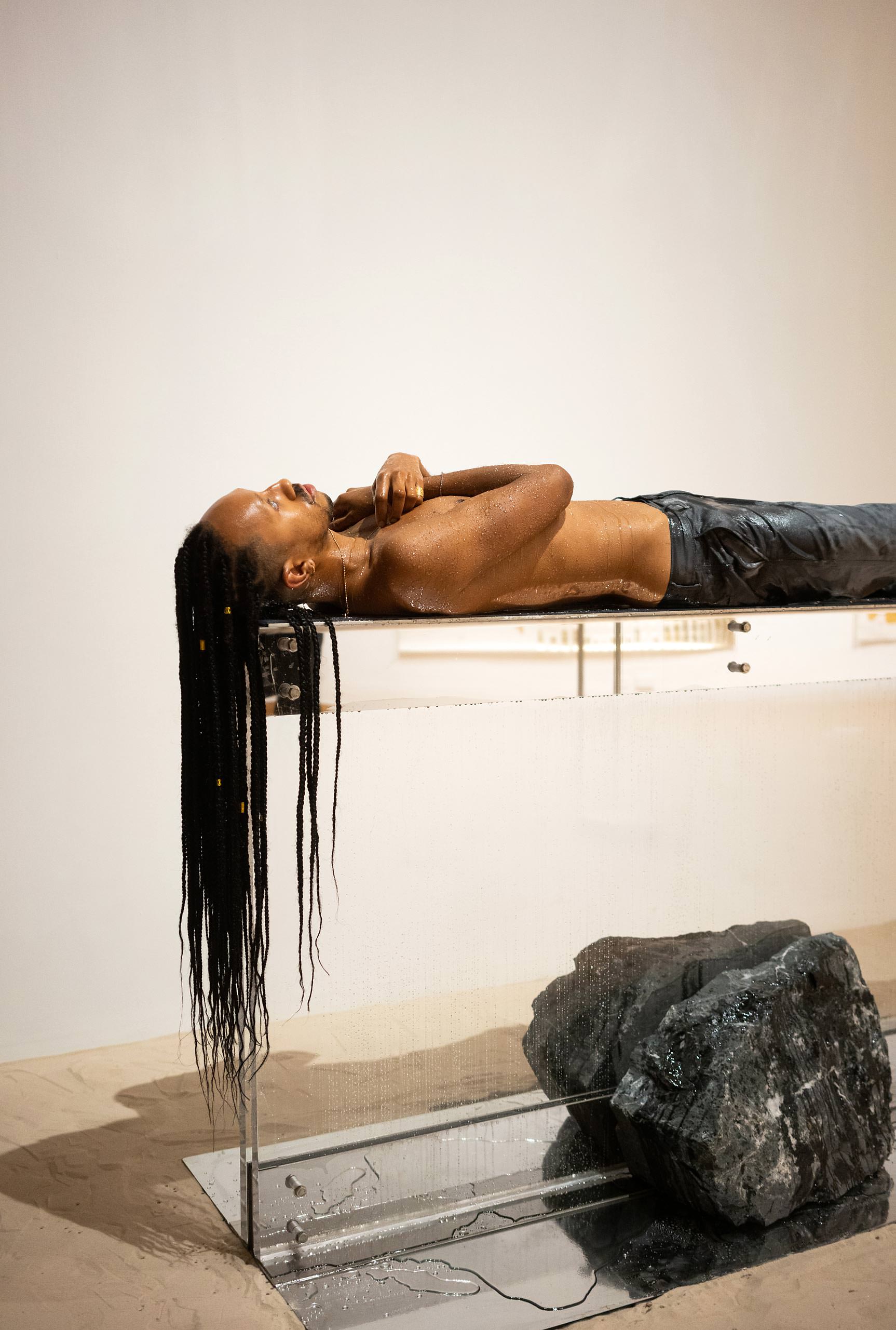

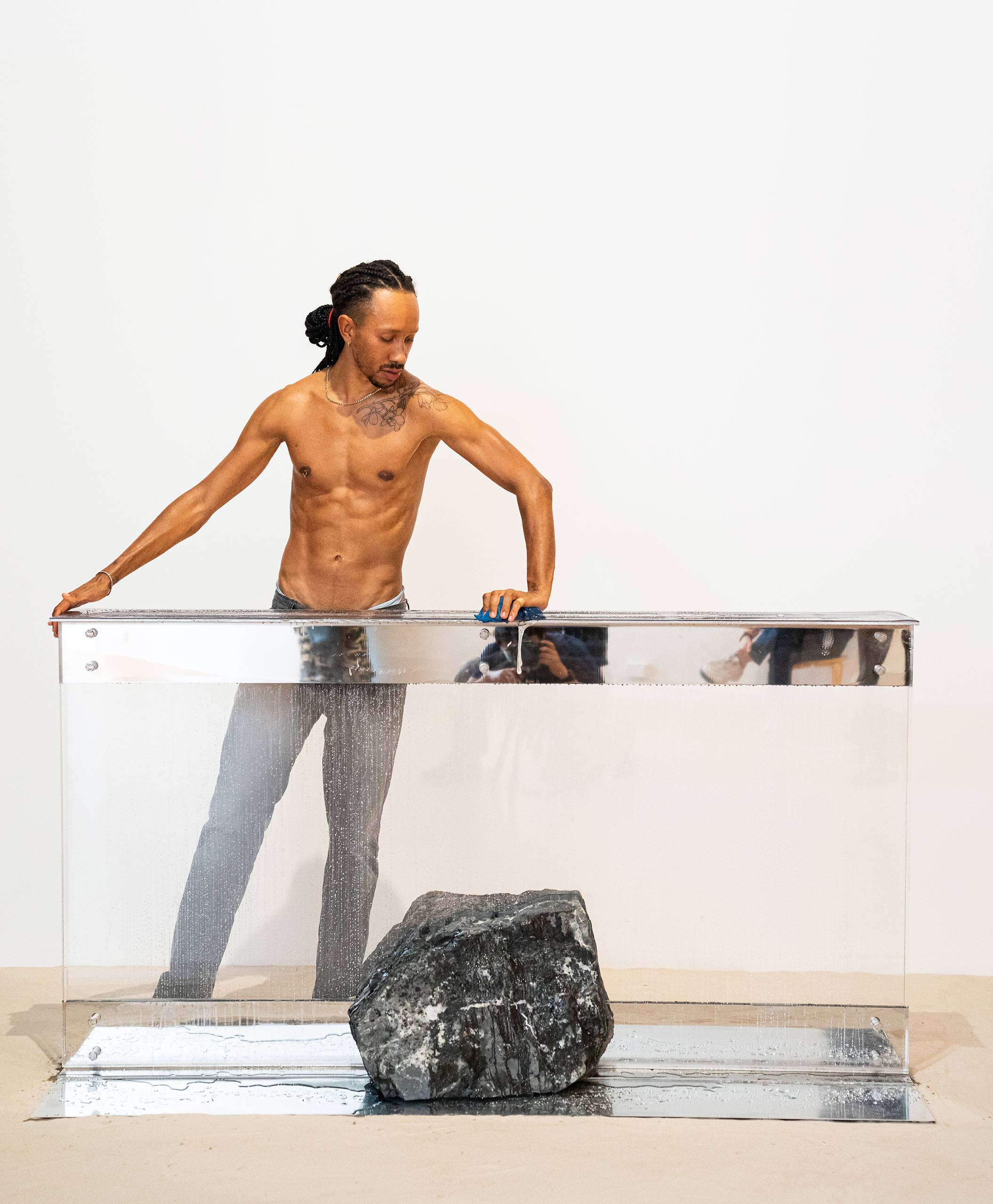

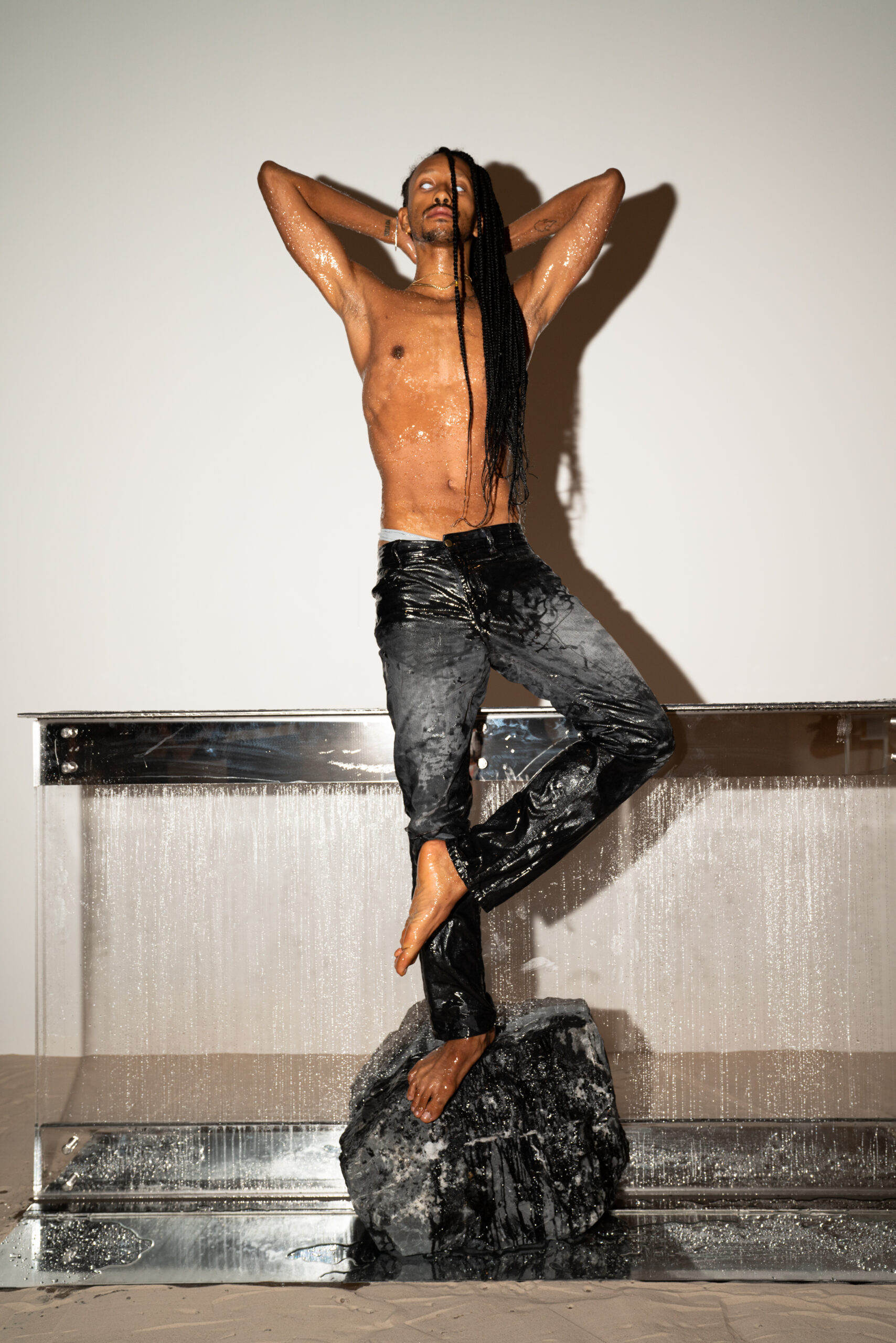

Pneumotherapy (II) (2020) at Perrotin in New York. Photo by Maria Baranova, courtesy of Miles Greenberg.

Pneumotherapy (II) (2020) at Perrotin in New York. Photo by Maria Baranova, courtesy of Miles Greenberg.

Pneumotherapy (II) (2020) at Perrotin in New York. Photo by Maria Baranova, courtesy of Miles Greenberg.

Indeed, when we consider Greenberg himself, his work becomes all the more profound, even relatable, as we witness him pushed to his extremes. Oysterknife (2020), a work that will undeniably define his career, is a full-day odyssey “through the peaks and the valleys of every range of human emotion imaginable,” he says. The artist walked nonstop for 24 hours on a conveyor belt, with no external stimuli, in Montreal’s Phi Centre, while a live stream played on monitors outside the centre for the public to watch. At hour 16, he passed out for 25 minutes—he wasn’t roused, at the request of Abramović, who told the guards standing by to give him up to an hour to get back up on his own. He did, and resumed walking. At hour 18, he had thought every single thought he ever had, his mind blank in the truest sense of the word. At hour 22, he started dancing.

“It felt like voodoo. Something took over my body. It was quite beautiful,” he says, recalling being overcome with euphoria. “Every culture around the world has tried to get out of their body in some way or another. I’m quite obsessed with the idea of religious ecstasy. I think there are many avenues to get there, but to do it just from your body alone. I mean, that’s power.”

_________

While narrative forms require arcs and structure, Miles Greenberg’s performances are moments suspended and unfolded in minute scales.

Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy of Miles Greenberg. Late October exhibit.

Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy of Miles Greenberg. Late October exhibit.

Greenberg’s work is accompanied by a sense of ritualism before, during, and after performances. He eats one half of a papaya before, for instance, and the other half after, he tells me. (His second half after the 24 hours of Oysterknife was quite brown, he laughs.) His performances, too, play out as reverential forms of ritual, something he attributes to his obsessive-compulsive disorder, which he was diagnosed with in his late teens. “My art practice is essentially a sublimation of my obsessive-compulsive disorder,” he says. “I approach my whole life in rituals, and I think that finds its truest form in my work. I’m lucky enough to say that it doesn’t feel like a disorder anymore. My work comes from these very compulsive or, as André Breton would say in Mad Love, convulsive gestures that I think, ultimately, are all gestures of love.”

Greenberg’s work, at its core, is a visceral exploration of physical and mental edges. To think that within those extremes—at the brink of human capacity—remains love is a soft inclination that reveals the artist’s purest tendency.