Pavia Art Restorers

Art and craft.

Via Margutta has been home to every kind of artist and craftsman, including painters, sculptors, and poets. Mostly residential and lined with vining ivy and ochre stucco, cobblestones and window boxes, art galleries and artists’ studios, it is one of the most beautiful streets in Rome. During the 19th century, painters were arriving at Via Margutta in droves. Claude Debussy, Franz Liszt, and Giacomo Puccini are all said to have lived on Via Margutta. Igor Stravinsky, too, came here with his friend Pablo Picasso. The fountain at the far end of the street, Fontana delle Arti, is capped by a carving of a bucket filled with artists’ brushes. To this day, there’s an annual painters’ festival on the street.

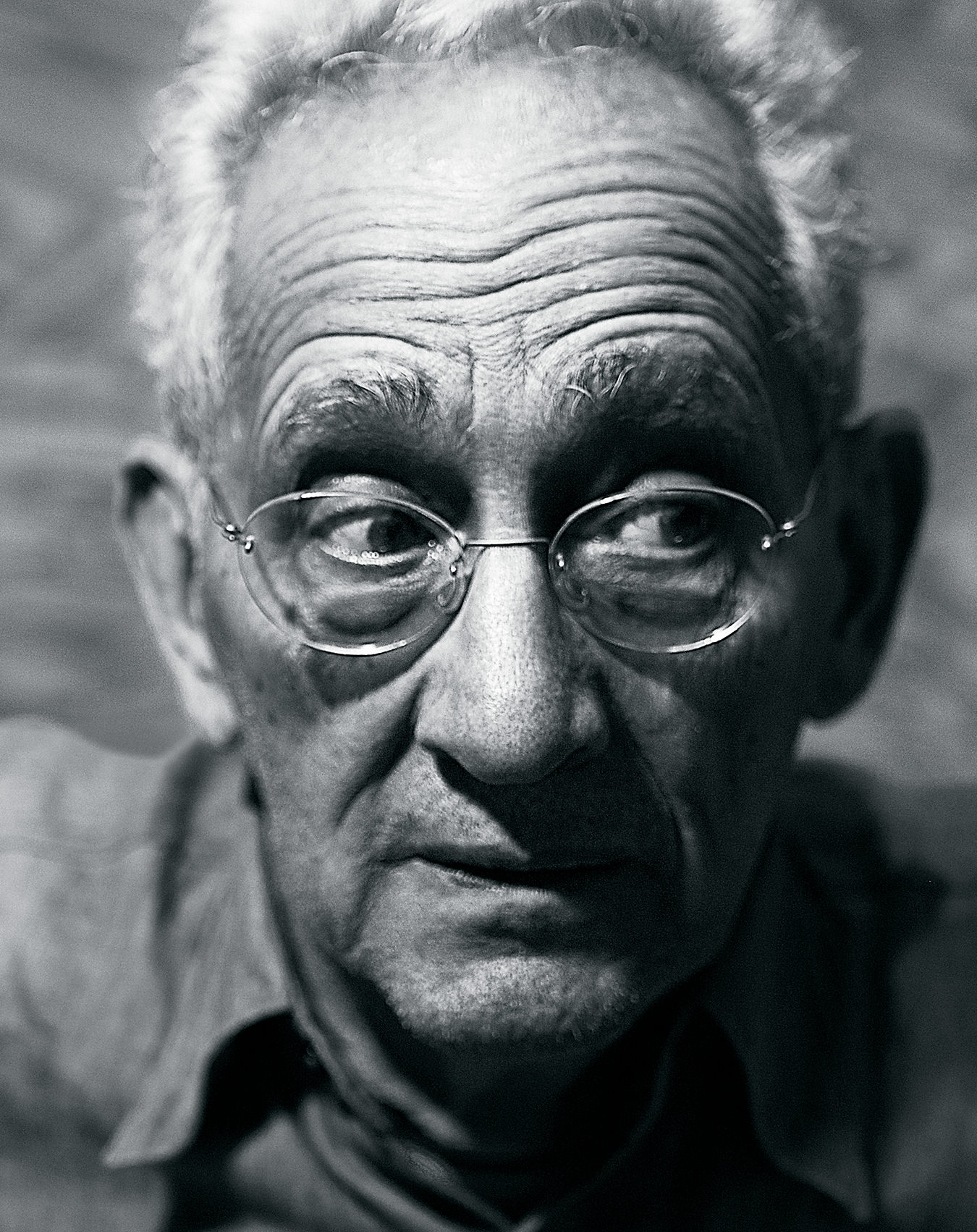

At number 54, Alessandro Pavia and Lycia Giola preside as artists of a different kind: the husband-and-wife team constitute the fourth generation of art restorers. They are two of only a handful of conservators in Rome who specialize in restoring contemporary art and have become particularly admired for their skill in working with organic substances. “Being a good art restorer is like being a talented cosmetic surgeon,” says Giola. “You never want your work to be obvious.”

In the studio, there is an oversized table on which works can be laid while they are being treated. The table is surrounded by standing lamps. Pavia is hunched over a Giuseppe Capogrossi, tweezing away Japanese rice paper while painstakingly repairing a botched job. Fine manual dexterity is essential for this line of work, as is the ability to see subtle differences in colour, texture, and finish. Prior to the Capogrossi arriving at the studio, a not-to-be-named restorer applied rice paper as a preservation measure—a practice Pavia vehemently rejects. “What we are trying to do is to keep the authenticity of the artwork,” says Giola, the English speaker of the couple. “How can you maintain the artwork and the aging process? That is the challenge.”

Pavia and Giola are continually testing new materials and examining their behaviours. “Just like in medicine, something you think is good now may not be good later on. We need to think of the future effects.” In the mid 20th-century, artists routinely worked with non-traditional materials. Often, the purpose was to reject the traditional materials of the arts—bronze, marble, oil paints—and the bourgeois cultural value. Now, it falls to conservators like the couple to make these contemporary works last as long as bronze or marble. For these artisans the best testament to the skill of their work is no one having a clue they have done anything at all.

The chamber of commerce in Rome and the Roman Institute for Entre-preneurial Training have developed Eccellenze Romane per l’Export (ERE), a multiyear project that aims to promote the excellence of Roman artisans.

“There is no work that is simple,” asserts Giola. “Every one is a strange situation, and we are in this strange middle between a chemist and a crafter.” Pavia, Giola, and their contemporaries are the masterful scientists of art.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter.