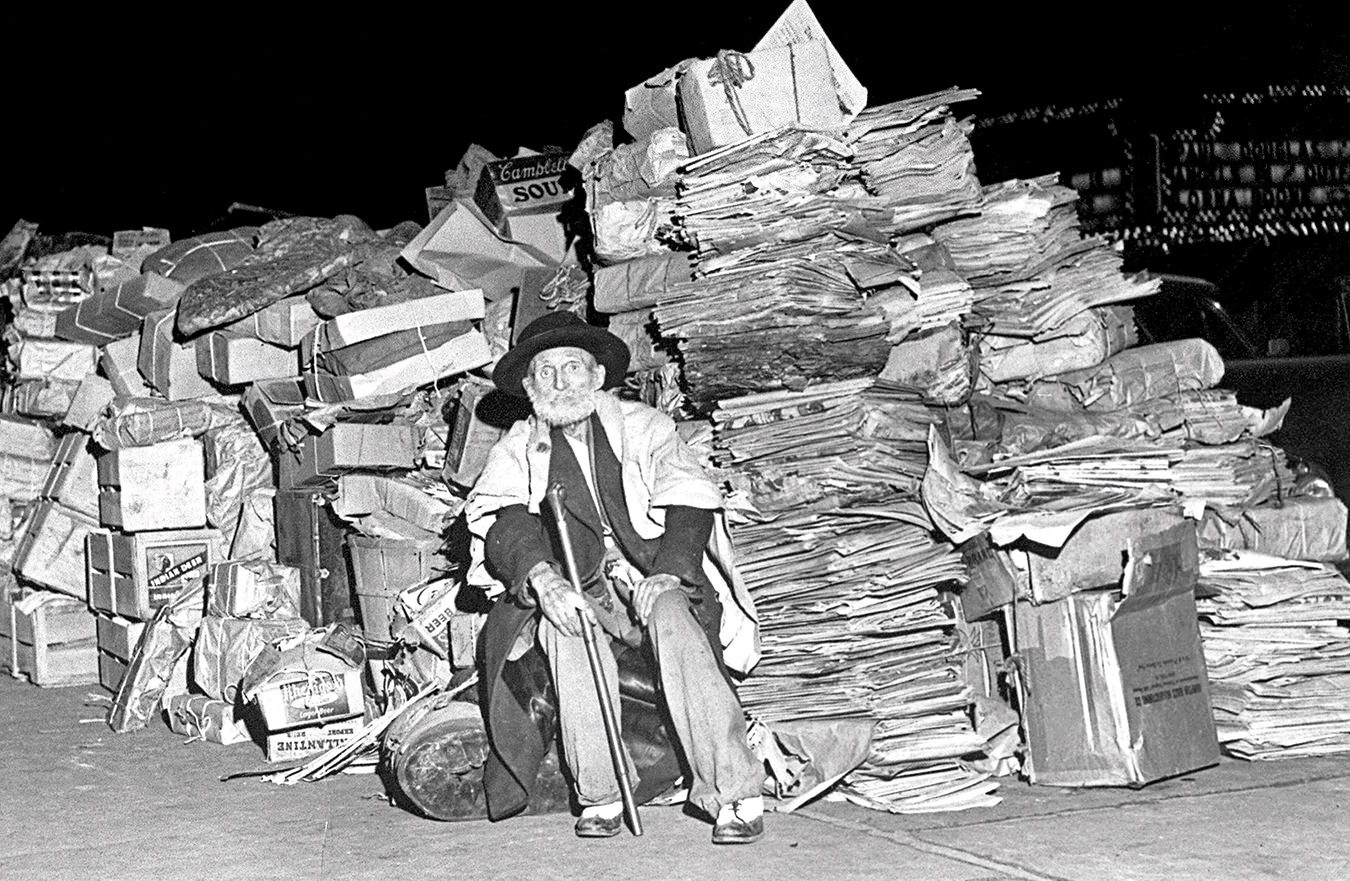

Scalawags: Edward John Trelawney

An outsized chap.

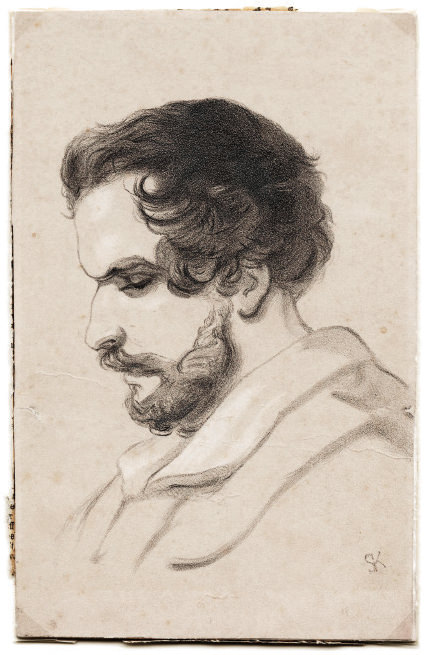

A mid-19th-century lithograph of Edward John Trelawny by artist Seymour Stokes Kirkup. ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

I knew Trelawny was a scalawag to the nth degree, but I also knew he had a reputation for being a liar and no more than a hanger-on in the circle of Romantics that revolved around the poets Byron and Shelley in the early 1800s. He certainly needed more investigation, which I have by now done. So how much is true, and why did the numerous chroniclers hate him so?

Edward John Trelawny was born in 1792 in Cornwall to parents so cruel and abusive that, at age 12, their son was relieved to be given over to the Royal Navy, to sail in the hold of an odoriferous, broken-down frigate and be bossed by uneducated brutes. He worked on various ships and sailed all over the world until deserting at age 19. In a billiard parlour in Bombay, Trelawny, armed with a sword, was about to kill an older sailor in a brawl when another man intervened, taking the blade and replacing it with a cue stick. Thus Trelawny severely beat the man rather than killed him. The tall, dark, and handsome stranger told Trelawny to flee at once and wait for him at a certain brothel in Dungaree. Two days later, the stranger showed up and introduced himself as De Ruyter, privateer, sailing under a French letter of marque.

According to Trelawny, he spent the next seven years aligned with De Ruyter, who spoke six languages fluently, read philosophy, and could quote reams of poetry. Trelawny modelled himself on this man who knew people around the world and was involved in all sorts of intrigues. They sailed together, mostly in the southern seas, attacking slavers and taking prizes, many of them British. Trelawny married an Arab girl called Zela whom he had met during a raid on a city of slave-owning pirates on Madagascar. A year later, Zela was poisoned by a rival for Trelawny’s affections. During his times as a corsair, Trelawny was shot and knifed several times, and he killed several people (who, he insisted, needed killing!).

One fabulous adventure followed another until Trelawny and De Ruyter fled before the impeding assault on Mauritius, their base of operations, by the English under Lord Minto. They sailed to St. Malo, where De Ruyter had dispatches to deliver to Napoleon. Trelawny was taken by a Guernsey smuggler leery of travelling to shore and was set down on the rocks; he soon learned that his hero, De Rutyer, had been killed in a battle at sea.

Almost a decade of fabulous adventures had come to an end.

“Or so he said,” his biographers write. They don’t believe he did what he said he did, yet declare, “For long intervals we do not know where he was living or what he was doing.” People later remarked on Trelawny’s many wounds, obviously inflicted by bullets or knives, but gave no credence to his stories about obtaining them.

Why was Trelawny so regarded (or disregarded)? The answer lies in what came next. In 1822, he was introduced to Percy Bysshe Shelley, who introduced him to Lord Byron. The latter, the ultimate would-be romantic hero, took one look at Trelawny and heard his tales of adventure and must have wanted to run and hide. Byron had gotten famous for a poem about a dashing corsair, and hinted that the work was, to some extent, autobiographical. Then along comes Trelawny, with his long, flowing hair, black moustache, absurd athletic prowess, and a violent, scarred past—the very model for what Byron had written. Worse for the class-conscious Byron was that Trelawny came from the same class, the upper, but couldn’t have cared less. And what made it even more frustrating was that Trelawny looked the part of the corsair, and Byron—flabby, pale, and hobbled (not by a club foot, as often thought, but by shortened Achilles tendons)—did not.

The women of Shelley’s circle—and particularly Shelley’s wife, Mary, author of Frankenstein—gushed over the newcomer. “He is extravagant,” she told her diary, a few nights after they met. “[He] has the rare merit of exciting my imagination.” And later in a letter to a friend she wrote, “He is clever; for his moral qualities I am yet in the dark; he is a strange web which I am endeavouring to unravel.”

When Shelley was killed in a boating accident, it was Trelawny who handled all arrangements and even built the pyre on the beach where the great poet’s body was burned. When only Shelley’s heart remained, Trelawny is said to have reached into the fire to seize it. That spontaneous gesture would make him famous, or infamous.

The war for independence had broken out in Greece, and not long after Shelley’s death in 1822, Trelawny and Byron left for Greece in a newly refitted chartered ship that carried furnishings, linen, silverware, five horses, two dogs, and eight servants. Byron rented a house in Missolonghi. Trelawny, however, joined the fighting immediately and soon became attached to the rebel leader, Odysseus Androutsos; he was considered the purest of the vying rebel warlords, uncontaminated by political ambition. Trelawny became his second-in-command. After raids, they would repair to Odysseus’s stronghold on the north side of Mount Parnassus. The men were so close that Trelawny married Odysseus’s half-sister, Tersitsa.

When Odysseus was captured and imprisoned, Trelawny became the leader of the rebel faction. He was shot twice by British spies but survived. While he lay wounded in the caves, Odysseus was murdered in custody. Another rebel leader allowed Trelawny to be carried down from Mount Parnassus and taken aboard a ship bound for Italy.

Trelawny was sought-after as a guest at certain dinner parties—but not those of the conservative intelligentsia—where he yarned about eating human flesh, walking across the desert dressed as an Arab sheik, and knowing of buried treasure.

Trelawny’s exploits in Greece are well documented because the independence movement was a popular cause in England. Thus, all his swashbuckling, guerilla fighting, heroic horseback charges, and romancing dusky women in exotic locales can be shown to have actually happened. Most of it was witnessed and much of it made the papers. “Greece was the only time,” sniffed one biographer, “that Trelawny came close to living up to his romantic image of himself.”

A recent biographer begs to differ, insisting a scared Trelawny actually “hid in a cave during the revolution.”

In Florence, he rented a house for his young wife and their new child, whom he named Zella, after his previous wife. There he recuperated and wrote a semi-autobiographical book about his youthful exploits, Adventures of a Younger Son.

Between 1826 and 1828, Tersitsa left him and their child (Zella was attending boarding school in Lucca and remained there to be adopted) and returned to Greece. In early 1833, Trelawny arrived in America. In New York, he met the famous English actress Fanny Kemble, who was on tour with her father. They travelled together to Niagara Falls and then into Canada. The last time Trelawny was seen that year was on December 2, in Charleston, South Carolina, where he paid £1,000 for a black male slave and sent him to Canada via the Underground Railroad (the receipt of purchase still exists). This was not the first time he had bought and freed slaves. He’d done it throughout Asia and in Greece.

Then he disappeared. “For the first ten months of 1834, we do not know where he was or what he was doing,” wrote one author, adding, “Stories that he crossed the continent to California cannot be true.”

He reappeared in Philadelphia in December 1834, and left for England “with a red Indian girl picked up somewhere on his travels.”

The next year, he married again, to one Augusta Goring, and for 12 years lived peacefully in the country, building stone walls and planting flowers and trees. It is rumoured that he conducted affairs with many village women. During those years of domesticity, he wrote a book about his relationships with Shelley and Byron and that circle, which only incurred the enmity of the literati and added to his notoriety.

On visits to his club in London—appropriately called the Savage Club—awestruck visitors lined up to shake the hand of the man who had held the heart of Shelley and helmed Byron’s ship.

Trelawny was sought-after as a guest at certain dinner parties—but not those of the conservative intelligentsia—where he yarned about eating human flesh, walking across the desert dressed as an Arab sheik, and knowing of buried treasure. He hit it off with the American poet Joaquin Miller, “the Poet of the Sierras”, taking him aside to reveal the location of a shipload of gold hidden near the San Diego harbour.

Trelawny was 65 when his final marriage broke up, and after two months spent driving around the coasts of England in his carriage, he retired to a cottage in Sussex, where he became notorious among locals for his eccentricities. He painted his cottage red, wore no overcoat and no socks, and in his 80s could be seen chopping wood outside in the winter. He ate no meat and drank no alcohol. He frequently gave his possessions away to strangers. He received visitors to whom he retold his stories, promoted revolution, and argued for equal rights for women.

He sat for Sir J. E. Millais as the model for the old sea captain in Millais’s painting The North-West Passage. After seeing the picture for the first time, Trelawny went to his house to challenge him to a duel.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, the poet, came to see him and declared, “There is some fresh air in England yet while such an Englishman is alive.” In his 81st year, Trelawny was “a magnificent old Viking to look at,” said Swinburne. Strangers also showed up. He wouldn’t let them in, but they were content to stare at him on the other side of the fence as he chopped wood, for he was, indeed, a legend.

His best friends were a pair of dogs. He went every day to the village pond to feed the ducks. He died in his sleep at age 88.

Trelawny remains too outsized a character for many to reckon with. But those knife and gunshot wounds—the one across his neck, those on his back, legs, side, and chest? His critics have explained everything else away, but have not figured a way to deprive him of his scars.

Image ©National Portrait Gallery, London.