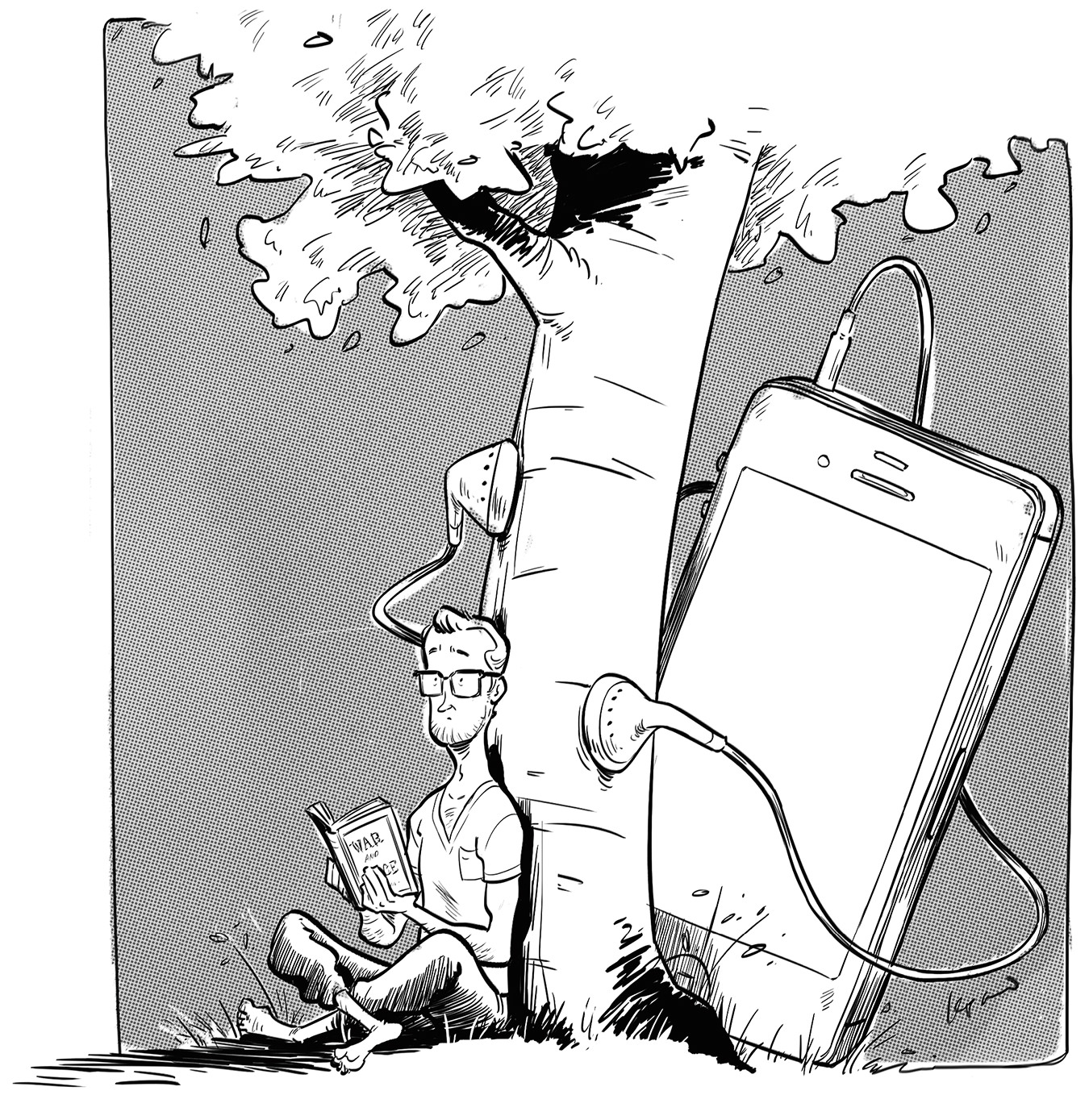

Attempting to Unplug

Solitude in the age of screens.

There were then two glowing screens atop my desk; three, if you count my yappy little phone. I was a magazine editor at the time—or, as we now say, a “content creator.” Yet I spent my days not so much creating content as reacting to it. Like most folk in the Age of Screens, I found my brain crowded with digital stimulus. So much so that I finally broke down and took a digital sabbatical. I quit my job and decided to spend one whole month offline—no Internet, no mobile phone. Hello, 1994.

What happened next is hard to explain, now that I’m online again—looking back at the offline world from inside the maelstrom of digital life, it can seem so quiet, so small. So nothing. In some ways it is: For every minute of “real life” that goes by, we upload 100 hours of video to YouTube. For every second that passes, we tweet 6,000 times. In fact, 90 per cent of the world’s data was created in just the last few years.

At first there was, naturally, a wave of loneliness (loneliness being a sign that we don’t know how to be alone). But, like a drug addict with a glimmer of an idea about what’s best for him, I sweated it out. I even kept a journal.

Day 3: Impulse to check e-mail continues unabated. Definite sense that am maiming own career and have grown certain that lucrative book/movie deals are expiring in my inbox. I keep picking up the land line, meanwhile, expecting dozens of messages. In fact, when people see you’re offline, they just write you off for dead.

Day 8: I dream of e-mail. All night I crafted perfect missives to Barack Obama. Alas.

Day 14: No epiphany yet. It’s still hard (though not physically sick-making, anymore).

Day 19: Did a Where’s Waldo? at the café today. Shocking bad sign.

Day 22: We just can’t handle solitude without a rich interior life. At first there was this bewildering, windswept void where my online world had been. Now, haltingly, I place other things in that void. A book. A walk through the neighbourhood. But nothing—nothing—is as enthralling as the absence-destroying Internet.

Looking back at these passages, I note that I sounded like a junkie.

At the time, people kept asking what I thought I’d get out of this reverse Rumspringa. There was a sense I was wearing a hair shirt, beating myself up for moralistic reasons. Soon, surely, I’d quit being such a superior prick and join Facebook again. At one point, just before I unplugged, I was interviewing Douglas Coupland and mentioned my plan. He was kind about it but his words still stung: “You can take a sabbatical from the Internet if you want, but it’ll be like taking a sabbatical from shoes.”

He was right, of course. We are the first generation in history to have more interactions with avatars of people than with actual people. To go offline is to go off-life.

And yet. Tech guru Jaron Lanier wrote that “one good test of whether an economy is humanistic or not is the plausibility of earning the ability to drop out of it for a while without incident or insult.” This seems a good gauge to me. We need to keep pushing back for solitude because the forces pushing the other way, toward clicking and connecting (mega-faceless-corporations, let’s face it) simply aren’t looking out for us. We have to be smart about our own media diet the same way we’re smart about our food diet.

So, now that I’m back online, I make those choices every day. I come back to the park with a book. I leave the phone at home (some days). I batch-process e-mail instead of letting it run like a stream in the corner of my attention. Once you force yourself to take a break from the digital game, you find the fear of being alone, the fear of being disconnected from hundreds of so-called “contacts”, starts to look infantile. It reminds you of a toddler, afraid of the dark.