Scalawags: Timothy Dexter

An eccentric American merchant.

There really was a man who shipped coal to Newcastle, and what’s more, he made a fortune doing so.

Timothy Dexter, who referred to himself as “the first Lord of America”, was regarded as simple-minded, though funny and irascible. He had a head full of ideas and more energy than 10 men, and he loved to take a chance. Lesser men, though of a higher station in life, enjoyed presenting him with the silliest business ideas they could think of.

When he sent bed warming pans to Barbados (this after selling a ship’s worth of mittens in Jamaica), they were accompanied by a note to his agent there, ordering the man to affix handles, after which the entire lot was bought and used as ladles for the molasses industry. After this exploit, Dexter’s betters in the town of Newburyport, Massachusetts, vexed by the upstart’s luck, told him he should next send coal to Newcastle. Oblivious to the irony (Newcastle’s main industry has historically been coal), Dexter filled an entire ship—which arrived in England in the middle of a coal miners’ strike.

Back in the 1800s in America, society, particularly in New England, was rigidly structured. There were three class designations—upper, middle, and lower—and, more significantly, each of these was likewise broken down. People could only hope to rise one step within a main category. Dexter, who was born middle-lower, managed the seemingly impossible by rising to middle-upper. Dexter himself was not surprised by his catapulting to the near top of the heap, for as he later wrote of his birth on January 22, 1747: “On this day in the morning A grat snow storme—the sines in the seventh house wives mars Came fored Joupeter stud by houlding the Candel—I was to be one grat man.”

This “great event” occurred in Malden, Massachusetts. At the age of eight, he was indentured to a farmer for six and a half years. Then he apprenticed for three years in the leather trade. He learned to make britches and gloves, after which he walked from Charlestown to Newburyport, where he opened a shop.

Everyone acknowledges that the man became almost indecently wealthy, but not even serious Dexter scholars address the mysterious means by which he got his first money. In 1769, at the age of 22, Dexter was able to purchase his own store, and, shortly after that, to buy a boat. In 1770, he married a widow with four children, and bought a house. All this activity took an amount of money inconceivable to a young man recently indentured, or indentured at all. It calls to mind the line in the Ray Charles song about how “them that’s got are them that gets … how do ya get your first is still a mystery to me.”

The answer seems obvious, to this observer anyway: privateering. When trouble began brewing with the mother country, boats and ships from New England ports started preying on English ships. English captains had a habit of mistaking Newburyport for Boston (probably as a result of their proximity). Dexter must have been lying in wait.

Prior to the American Revolution, the Thirteen Colonies were governed by the Continental Congress, which issued its own dollars, known as continentals. For a time after the Revolution, the continentals were valueless. Nevertheless, Dexter bought them at pennies on the dollar. Several years later, under Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, the continentals became exchangeable at par, and Dexter made another fortune.

His ability to make money infuriated his betters, and even worse, his outrageous behaviour appeared to mock all they stood for.

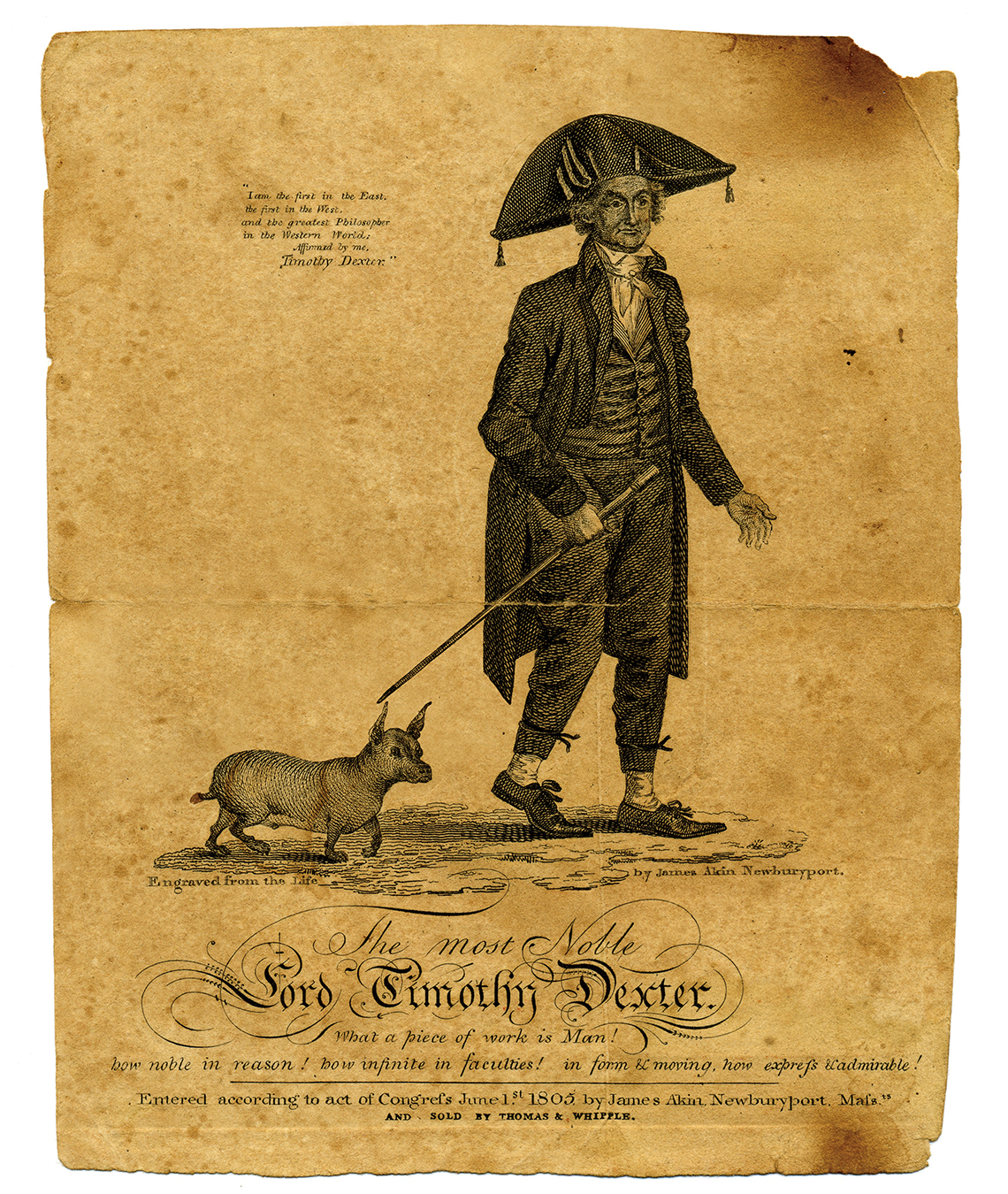

He spent money wildly and continued to associate with the characters he knew when he was a lowly glove maker. Tramps were always welcome at his door. He took advice from astrologers and fortune tellers. He bought a large house and a lion (a real live lion) to roam the grounds. He was seen in town trailed by what everyone thought was a pig but what Dexter insisted was a dog. Besides this animal, he had an entourage of rascals, soothsayers, and interesting drunks.

When not walking, he went around town in a luxurious coach drawn by a pair of cream-coloured horses, and would be driven past children skipping rope and chanting, “Dexter is a smart old man. Try and catch him if you can.”

Dexter often bought space in the local newspaper to tell the world of the troubles he had with his shrewish wife. He was not criticized too much for this, as everyone who ever met the woman came away agreeing with her husband.

Timothy Dexter took advice from astrologers and fortune tellers. He bought a large house and a lion (a real live lion) to roam the grounds. He was seen in town trailed by what everyone thought was a pig, but what Dexter insisted was a dog.

He bought his first ship while still in his 30s and eventually owned three. Ship owners occupied the upper-upper—but not ones who also owned lions and had necromancers to dinner and aired their private lives in print.

His last big score came when he bought 21,000 Bibles at 41 cents each. These he sent to the West Indies with a printed notice that every family should have one or else they would probably go to hell. He advised purchasers that it was necessary to kiss the Bible three times a day and pray to heaven. He sold them at a dollar a piece.

What he did next must have alienated him even more from the good folks of the town. He quit trying to make money.

Dexter bought an even bigger house with larger grounds and commissioned a sculptor to produce 40 wooden statues of men, women, and animals. These he put on pedestals. He had the three presidents of the Republic (George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson) on tall columns, but the positions of prominence were given to two columns featuring statues of himself. One at the east side of the grounds was festooned with a plaque that read “Number One in the East”. The other, on the other side of the grounds, read “Number One in the West”.

Of his statuary and outdoor oddities, including his own tomb with a glass summerhouse on top, he wrote, “I wants to make my Enemys grin in time Lik A Cat over A hot puding, and goue Away, and hang there heads Doun Like a Dogg bin After sheep.”

So here he was, a filthy rich loud-mouthed nutcase who had given up making money, turned his home into a museum, and had fellow oddballs over to sit on his French furniture. These included Madame Hooper, Dexter’s resident witch, famous for her double rows of teeth; Lucy Lancaster, also known as “Black Luce”, who eventually became his best friend; and his own poet, Jonathan Plummer, who had been following him for years.

Dexter hired the largest man in the country to carry him around the property when his gout was acting up. Some days he was friendly to visitors, giving them fruit, plying them with strong drink, and often making passes at women of all ages. He walked around with a large pair of scissors and rewarded children with a lock of his hair. One day so many people came to call that he was practically bald by nightfall. Other days, he was not so congenial. He served a day in jail at Ipswich for shooting a fellow who persisted in asking stupid questions.

Although only semi-literate, Dexter, in his last years, produced a book that has been in print for nearly 200 years, one of the classics of American literature: A Pickle for the Knowing Ones; or, Plain Truth in a Homespun Dress. It probably started out as an explanation of his museum, but his pen soon roamed over such topics as the real nature of the devil, the habits of religious figures he had known, his marital difficulties, the planning of bridges and highways, and a description of the beating administered to him by a lawyer in nearby Chester when Dexter was caught spooning with the man’s young lady friend. He wrote, “Nomatter what Dexter Rits, it Dus to make the Ladyes laf at the tea tabel.” And that it did.

But besides being a great work, A Pickle for the Knowing Ones knows no boundaries of subject or genre, and it also eschews punctuation. When readers complained about the lack of punctuation, Dexter brought out a second edition with a page at the end consisting entirely of question marks, periods, commas, colons, semicolons, and exclamation marks. He advised readers to use them to “peper and solt” the text as they pleased.

His last communication to the world appeared, as had so many others, in the local newspaper. A couple of weeks before he died, in 1806, he asked that learned men help with the matter that troubled him above all others, to wit: “Dus Angels hev wings?”

In the world of eccentrics and scalawags, Timothy Dexter was definitely beyond upper-upper.

Photo ©Boston Athenaeum, USA/The Bridgeman Art Library.