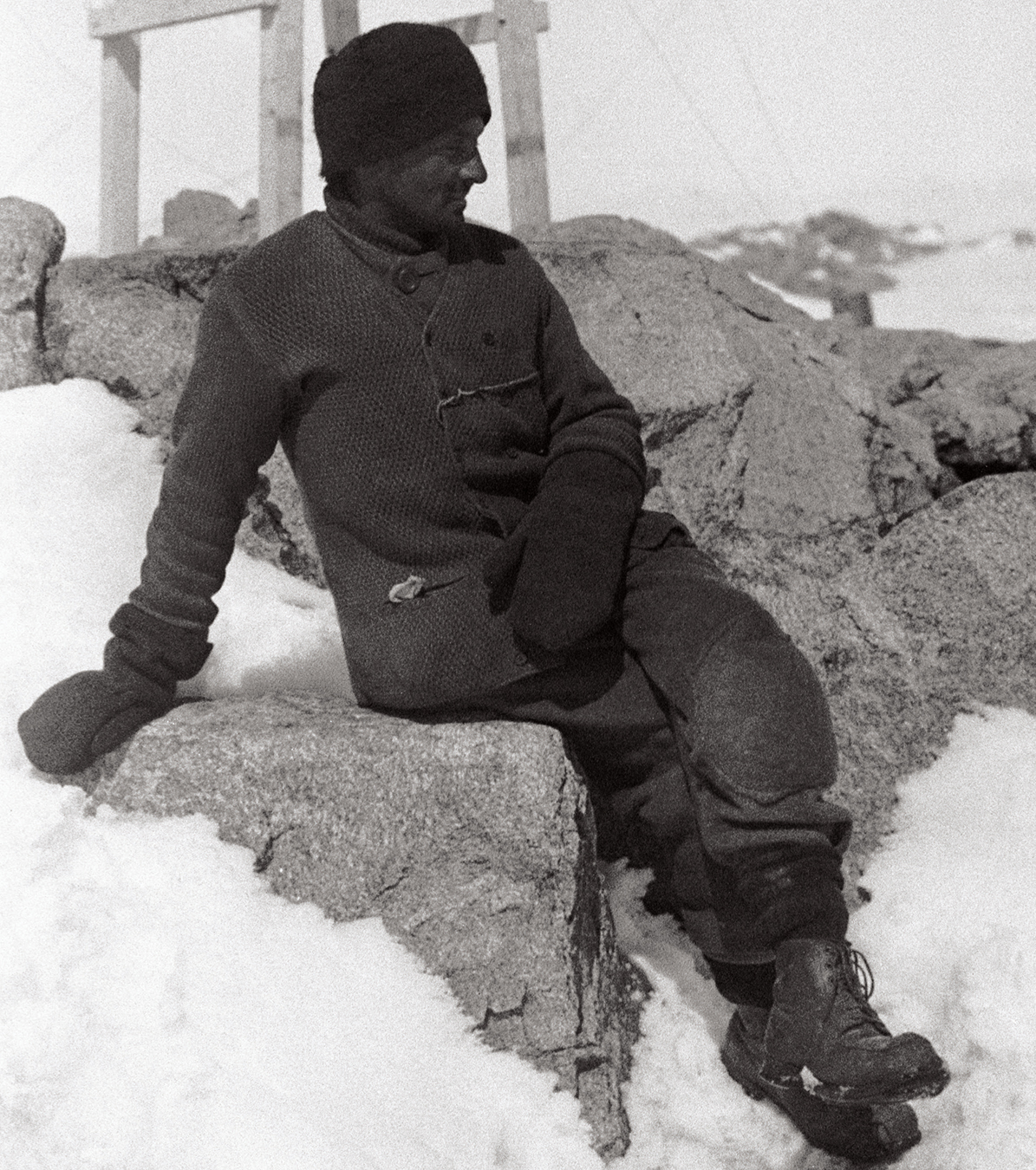

Scalawags: Herbert Dyce Murphy

The story-telling, world-travelling, cross-dressing spy.

Herbert Dyce Murphy never conned a greedy sucker out of his life savings or convinced the natives of tropical isles that he was the returned white god of their myths. The man didn’t even smoke or drink. And yet, in the roster of scalawags, he has to be near the top. He was a mystery wrapped inside an enigma, hidden in a mass of contradictions somewhere in the land of the unfathomable.

Imagine a dark night on the Mediterranean in 1902 and a yacht being thrown about on a wild sea. The lone passenger wakes to discover that the entire crew lies paralyzed in a drunken stupor. The passenger rushes on deck to rescue the ship from disaster. “I never got such a fright in my life,” he would later say. Not due to any danger from the sea, but because he was in a soaked negligee and certainly didn’t want to be seen that way. But he was no ordinary transvestite; he was, in fact, a spy for British Intelligence posing as a woman.

Born in 1879, Murphy divided much of his youth between a mansion in Melbourne, the family sheep station spread over thousands of acres in central Australia, and London, where he served as a sort of aide-de-camp to the Empress Eugenie, widow of Napoleon III and a distant relative of the Murphys.

It was obvious early on that he would not be the rugged Aussie he-man his father hoped for, nor did the boy want any part of such a life. At 14, he sailed from England to the Norwegian Arctic. He would ship out at every break during his years at boarding school. In his spare time he studied photography and taught himself to print and develop pictures. At 16, he spent an entire year on board a wool clipper. The next year he went on his first Arctic whaler and always seemed to be doing something heroic, rescuing people or taking over the ship when the captain was incapacitated. He became a second mate after only four years at sea.

Later, Murphy enrolled at Oxford but left to sign on a ship bound for the Gulf of Mexico because he would get leave time in New Orleans, which boasted a brand new railroad line. Murphy was crazy for trains.

Back at Oxford, he tried out for the school play and earned the eponymous role in Euripides’s Alcestis. “None of the young ladies who auditioned could recite the Greek,” he recalled.

As fortune would have it, the master of the college took as his guest to the play the director of British Military Intelligence, Sir John Ardagh. “Alcestis is a beautiful girl,” he said. “Who is she?”

When told the truth, Ardagh shook his head in wonder. “I suppose he’s quite effeminate?”

“Quite the contrary,” answered the master.

Within a couple of days, Murphy, or Dyce, as he was known, ceased to be a student and became a spy.

British Military Intelligence, fearing war with France, wanted extensive information about the state of railways on the continent and had been trying to gather it for over a year. Two agents had been discovered and sent home. Ardagh surmised that a “woman” might do the job undetected. Not only could Murphy look the part, but his interest in trains and ability as a photographer made him an ideal spy.

After a month of tutoring by a female crew, he emerged as Australian heiress Edith Murphy. Soon he was travelling in France and Belgium. During these trips he was often accompanied by an elderly sea captain. A painting exists of the two of them in a railway carriage. But it was another painting that helped make Murphy infamous. By E. Phillips Fox, it’s called The Arbour, and Murphy is supposedly the girl in the white dress. There are many who knew Murphy well that deny it. Not that they don’t believe he’s in the painting; they insist he is actually the woman in the striped dress.

On Christmas Day, 1901, Murphy and two friends from British Intelligence decided at the last moment to go to church. Murphy’s family had a pew in Holy Trinity, and, assuming his mother to be in Australia, he went there in disguise with his friends. But his mother was indeed in London and she showed up at church. She failed to recognize her son and was put out to see strangers in the Murphy pew. Murphy passed her a note: “I’m your daughter, Edith.” His mother replied with her own note: “I am so glad. I always wanted a beautiful daughter.”

This incident and the painting The Arbour later inspired a novel by Nobel Prize laureate Patrick White called The Twyborn Affair.

As is common with those who live outsized lives, many of Murphy’s stories have constantly been dismissed. Even those who liked him smirked knowingly where his adventures were concerned. Trouble is, nobody, not even his biographers,

can explain why his stories were not true.

King George VII took quite a fancy to Edith, and there is supposedly a photograph of the two together.

Rudyard Kipling was introduced to him and later said, “I frankly do not believe that was a man.”

But as Murphy got older, his skin became coarser, and dark hairs appeared on the backs of his hands. And he was becoming notorious. Finally, he’d had enough. After two months in seclusion in the Canary Islands, he shipped out as second mate on a whaler to Antarctica. Later, on another whaler in the South Pacific, Murphy got in trouble with the skipper for trying to get several naked island women aboard the ship.

In the north of Norway, he unofficially adopted two girls, aged four and six, sole survivors of an avalanche that wiped out their town. The local pastor had begged him to take the girls. They stayed with him for 12 years and accompanied him on numerous trips.

In 1911, he was one of only 28 men accepted for the Australasian Antarctic Expedition led by Sir Douglas Mawson. The surviving journals of crew members all mention Murphy keeping them in stitches with stories of his adventures and misadventures.

After the expedition, and after he was jilted by the woman with whom he was in love, Murphy spent many years sailing around the world for a whaling company, checking on supplies and establishing depots.

Back in Melbourne in the 1920s, he bought 16 hectares of land along the beach and opened his property to children and their parents. There was never the slightest hint of impropriety in his friendships with children, or with anyone else.

He devoted much of his later life to giving talks at various clubs and societies, for which he accepted no payment. It is known that he married in 1934, at the age of 54. But, as is common with those who live outsized lives, many of Murphy’s stories have constantly been dismissed. Even those who liked him smirked knowingly where his adventures were concerned. Trouble is, nobody, not even his biographers, can explain why his stories were not true. One biographer barely mentions the 15 years he spent providing a holiday home to children and never explored, or simply disregarded, the reminiscences of these people. And there were four young women whom he supported all the way through medical school. Some skeptics insist that after the 1920s Murphy never travelled at all. Yet one girl recalls how, during the Depression, he took her and her mother on board his yacht and they sailed to Ceylon and back.

Murphy used to say that during winters when he was in his 60s, he would ship to the Arctic. One doubter claims that records show he was actually in attendance at Melbourne city council meetings during these times. But they don’t, in fact, show that he was in attendance every winter, nor is there any record of him being anywhere else when he wasn’t in attendance.

He lived to be 91 years old and in his last few years could be seen walking or riding his bike around Melbourne. One girl, who had been at his estate during holidays, was visiting her mother in the late 1960s when she saw Murphy walking down the street with his hands held in front of him in handcuffs. She brought him inside and helped the old man get out of the cuffs and served him tea.

He passed away in July 1971.

Charles Laseron, assistant biologist on the Mawson Expedition, declared, “Herbert is a genius … his stories are convincing yet at the same time too impossible to be true.”

Laseron didn’t say why.

Murphy’s wife burned many of his papers and journals, including, supposedly, proof of a previous marriage. Among the material that survived were photographs of women that he’d taken in all parts of the world, as well as the King’s medal and the Queen’s medal for meretricious service in the Boer War in South Africa. No one who knew him remembered Murphy ever mentioning that country. Who knows?

Photo provided by the Mitchell Library, state library of NSW.