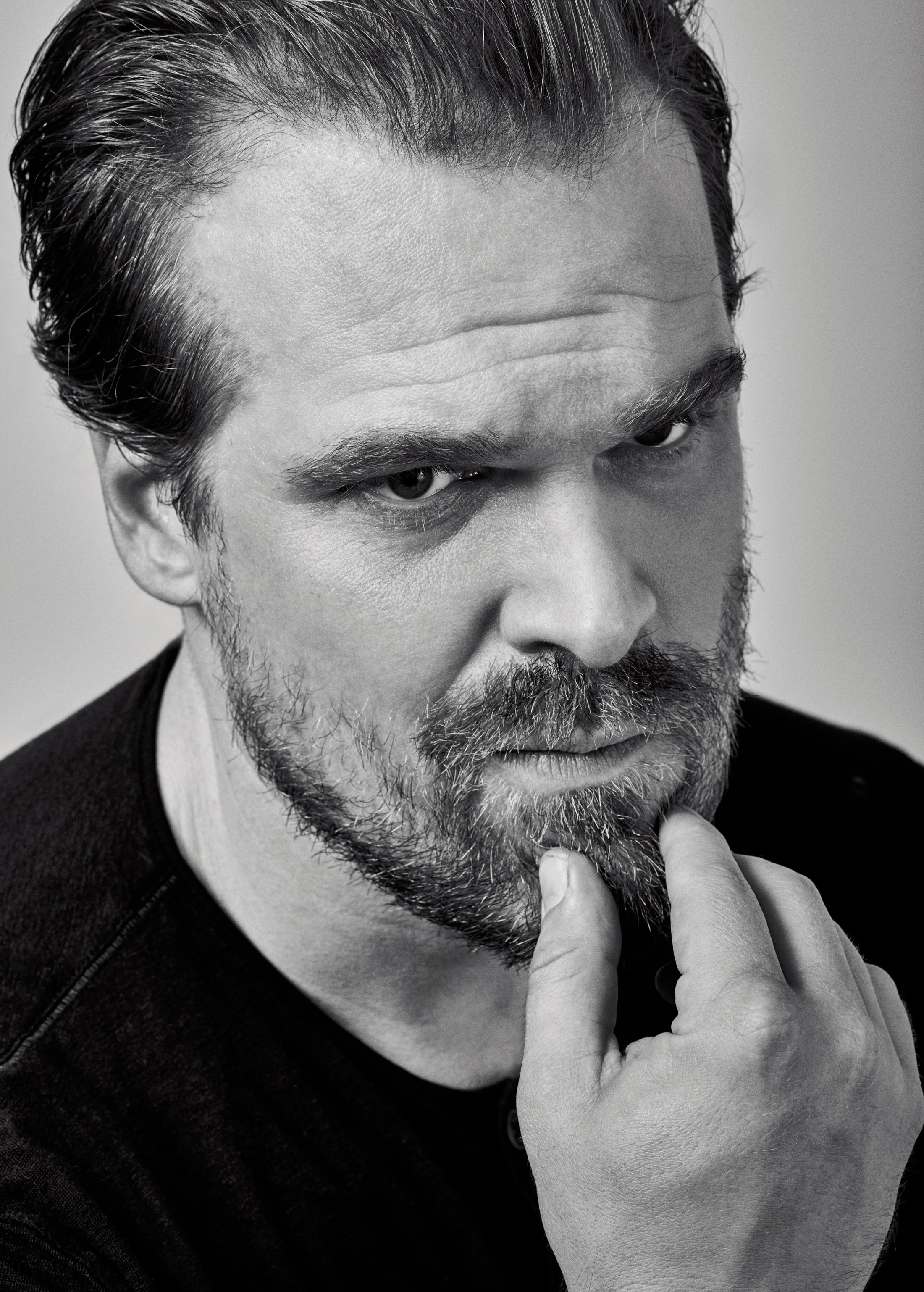

In Conversation with David Harbour

Harbouring emotions.

A big man with broad shoulders, deep-set eyes hidden under a baseball cap, and a jawline as thick and square as a dictionary, David Harbour doesn’t just walk down the streets of the East Village, he lumbers. The first time I see him, a sunlit day in late September, that line from the classic American folk tune “Dink’s Song” immediately pops into my head: “She had a man who was long and tall/Moved his body like a cannonball.” Is it the melancholic spillover of the allusion that gives the man an air of world-weary sadness, as if the force of gravity is stronger on him than on the rest of us? Is it that the residue of his breakout role on Netflix’s Stranger Things as police chief Jim Hopper, a decent man who can’t seem to get any breaks, still clings off-screen? Or is it something else?

After a handshake (firm) and eye contact (held), Harbour gets to the truth. “I pulled my Achilles tendon in a play about a year ago,” he says, explaining his shambling gait. That the play was Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida; that it was staged at New York’s prestigious Shakespeare in the Park; that Harbour was, himself, playing Achilles hedges the tragedy with bathos. As the 42-year-old lets out a rumbling laugh at the absurdity, his brow unfolds like a drawbridge. “It’s pretty ridiculous,” he says, “but if you have to tear your Achilles tendon, that’s the place to do it, right?”

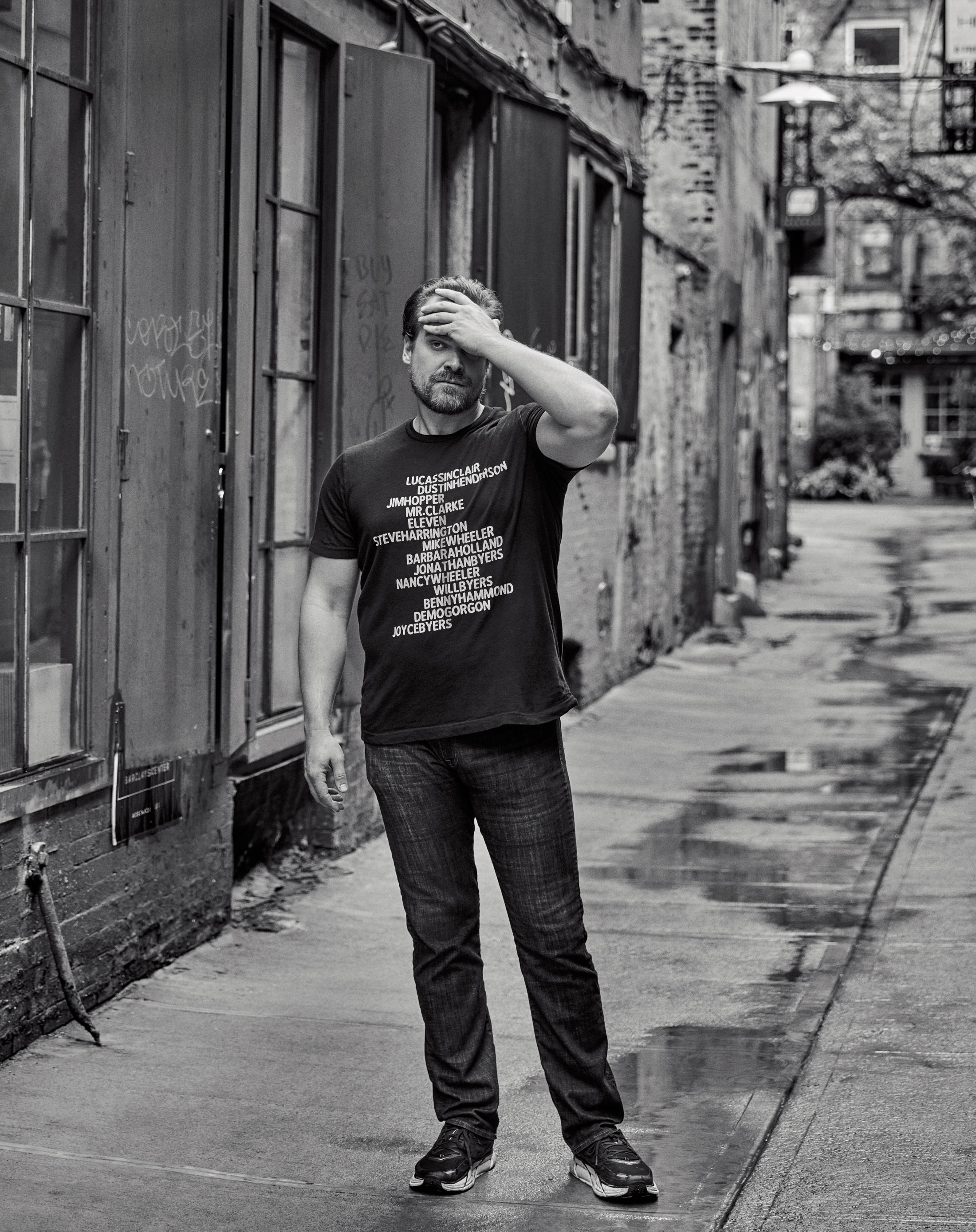

The injury laid our hero low for a few months, but now he’s back on his feet. Stranger Things, the much-ballyhooed Netflix show, which emulsifies the joy of an ’80s teen buddy flick with the creepiness of the paranormal and a maelstrom of adult emotion, is back for its second season. In a few weeks, Harbour will be off to Bulgaria to play the title role as a half-demon in Hellboy, and thus enter the money-making pantheon of superheroes. But today, he is concerned with his feet. “Ever since I tore my tendon, I have to wear these,” he says, pointing down at a pair of vaguely therapeutic-looking sneakers. “I go work out in them and I walk around in them, and they smell so bad. I want to find some kind of balls that you put in them, or something to, like, air-freshen them.” He’s already tried various shoe care modalities, though he allowed that his regimen was “unevolved”. We head through the East Village toward a sporting goods store near Union Square.

“I’m a sensitive weirdo [living] in the East Village who is an artist and not a guy,” says Harbour. “I’ve built this life where I represent the worlds I admire, but I’m not necessarily as manly as I portray myself.”

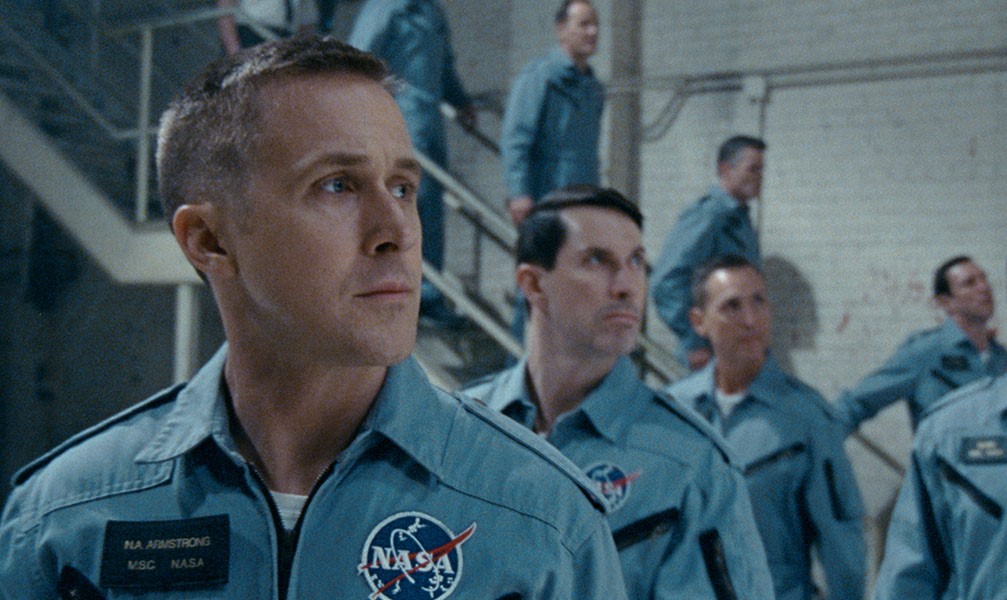

Harbour belongs to that category of great actors who are experts at withholding. He is more emotive than, say, Tom Hardy, who for the last few years has built a career on grunts and dirty looks. But much less so than, say, Ryan Gosling, whose sensitivity and emotional intelligence seeps through his perfect Canadian pores. But like Harbour’s cinematic forebears—Wayne, McQueen, Eastwood, Hackman, and Brando—if there is ever an option to do less, to speak less, to press his lips together and hermetically seal the hurt inside, he will avail himself of it. Besides the adorableness of the child actors; the virtuosic performance of Our Lady of the Micro-expression, Winona Ryder; the Spielbergian cinematography and writing by the Duffer Brothers that is as strong as any of Rod Serling’s best episodes of The Twilight Zone; it is Harbour’s performance as Hopper that has assured Stranger Things’ membership in the club of prestige television. His inscrutable character is suffering wrapped in flesh and a uniform. Asked to submit one episode to the Television Academy for this year’s Emmys (he lost to John Lithgow as Winston Churchill in The Crown), Harbour chose the finale of the first season, “Chapter Eight: The Upside Down”, which heartbreakingly ping-pongs between Hopper’s present emotional catatonia and joy-infused moments while his daughter was still alive. The warp and weft of emotion knot into a sturdy naturalistic fabric—canvas, perhaps, or worn-out, lived-in denim. But the actor has built his career not on light, but on darkness. Peak David Harbour is landscape-like, with features nearly still in the changing light. Aquifers of emotion run subterranean beneath the barren land. And yet, for its quiescence, every gesture becomes pregnant.

Though his brow is chiselled, in person Harbour is, of course, not a sheer rock face. He’s funny and talkative and, in his heart, an artist. “Ultimately,” he says, “I’m a sensitive weirdo [living] in the East Village who is an artist and not a guy. I’ve built this life where I represent the worlds I admire, but I’m not necessarily as manly as I portray myself.”

Passing dive bars turned third-wave coffee shops turned banks, he remembers taking the Metro North train from White Plains, New York, where he grew up, into the city on weekends to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There he’d stand before paintings like Jackson Pollock’s Number 28, 1950, a polyphonic spree of black and white lines, and Mark Rothko’s windows of luminous colour. Even as a tween, Harbour was touched by the non-verbal power embodied in the work of New York’s abstract expressionists. For they too danced on the border between the stoic damaged goods of the silent men they admired and the sensitive world of an artist. Afterward he and his friends would get buzzed at local cafés, ordering Irish coffees. “It sounded normal enough, but it had alcohol in it,” he explains. “If you got caught, you could say, ‘I just thought it was coffee.’”

After college—Dartmouth, an Ivy League school in Hanover, New Hampshire, which he calls “not the best choice for my artistic life”—Harbour moved into a shoebox apartment in New York’s Gramercy Park in 1998. With a few friends, he formed a theatre company whose repertoire included obscure plays mounted for pennies and performed for few. He made do on $1.75 kielbasa breakfasts at Leshko’s Coffee Shop (now a pan-Latin restaurant and bar), drank a lot, and hurt for work. He waited tables briefly but, having not yet honed his persona as a fundamentally decent guy saddled with silence, was reprimanded for looming. “My maître d’ said, ‘David, look at you. You’re so big, you look like you’re going to jump on the table. Everyone’s terrified. Get in the kitchen.’” Anyway, he said, “I never wanted my side job to be anything that I could actually do. Acting had to be the only thing. It had to be a do-or-die thing. If I got involved in a situation where I could actually go to work and feel good about it, I would be fucked.”

“I never wanted my side job to be anything that I could actually do. Acting had to be the only thing. It had to be a do-or-die thing.”

A few years into his New York residency, Harbour landed a role as a bumbling correctional officer on the soap opera As the World Turns. In soaps, he says, actors are just sherpas for a plot that will long outlast them. Instead of true acting, he discovered, there are just tears. “People just cry all the time,” he says, “so there’s no value anymore in crying.” Though Harbour never shed a tear as a soap actor, there followed a string of bit parts and coulda-been characters on cancelled shows that sustained the actor for a decade. But as his IMDb page grew, Harbour always seemed to be on the periphery. He was distractingly talented in, for instance, Revolutionary Road and Brokeback Mountain, like a beautiful, ancient elm seen out the window of a speeding car.

But roadside he remained. The resonances of his performances were still too minor key to make a leading man; he still loomed imposingly at the edges of the screen. There, Harbour developed his technique as a language of gesture. He worked against the overemoting of the soaps with an admiration for the men of the Silent Generation—men like Jim Hopper. “Today,” he laments, “you constantly have to be in touch with something, as opposed to taking action. What I like about the olden times is you don’t cry, you get shit done.”

Perhaps in a Hollywood peopled by handsome sprites, Harbour’s brand of Marlboro masculinity was too unsettlingly obscure. Then the times got darker still: the studios that shunted Harbour to the margins became irrelevant, art began to flourish again on the small screen(s), and a show like Stranger Things, which is a stranger thing than most, actually became viable. The world was in need of a big-chinned, clench-jawed, uneasy hero, who spoke little and seemed to be hiding something. It was time for Harbour to move centre stage.

Perhaps in a Hollywood peopled by handsome sprites, Harbour’s brand of Marlboro masculinity was too unsettlingly obscure.

David Harbour takes a deep breath at the gates of Paragon Sporting Goods and says, “Are you ready?” It’s crowded in there and smells like tennis balls and teen spirit. We pass the racquets, the bathing suits and goggles, until we hit footwear. Harbour scans the racks and spies a tube of Shoe Goo, a sort of polymer sealant used to extend the lives of sneakers, and the almost imperceptible wince that flashes across his face is noticeable. “Shoe Goo. My dad used to have that shit,” he says. “It’s like, ‘Dad, just buy a new pair of sneakers. It’s been 40 years.’ Such a kid of the Depression.”

As we browse, his tone and that comment stick with me. There seems to be something more than typical teenage disdain for an old man’s thrifty ways. Perhaps I’ve found the heart of the dark matter that gives him his disproportionate gravity. I say, “You know, you’ve been talking about the beauty of the strong, silent type. [Beat.] Tell me about your dad.”

Here, the silent Harbour of the screen and the affable one in person meet. We peruse footwear care in silence for what feels like an uncomfortably long time. Then Harbour says, “He’s a real good dude. My dad grew up with a very strict father in Yonkers and, later, Houston, Texas. My dad’s dad worked for Texaco. My grandfather was really upset that I did Brokeback Mountain,” he explains. Another pause. “In a sense, my dad is a man who was transitioning from a way of being that his dad represented to more of what I guess I represent now. He had a bunch of rigidity, but he also played piano.”

For a while we’re quiet, as if there is something more that is left unsaid. Then Harbour’s eyes light up. “Sneaker Balls!” he exclaims, with the enthusiasm of a true smelly foot sufferer. There are various colour schemes and, because he is so soon headed to Bulgaria, where Sneaker Balls might be hard to find, Harbour takes two packages. One is aquamarine and teal, the other is tie-dyed. “Just to be weird,” he says, grinning. Whatever clouds passed over the actor’s features earlier have dissipated. His Achilles tendon is almost healed, he’s found his Sneaker Balls, and it’s a beautiful day to be David Harbour indeed.

Grooming by Charlie Taylor for Tracey Mattingly using Tom Ford for Men.

Article originally published November 14, 2017.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.