Stakes In The Fertilizer Business

Potash problems.

In normal times, the business of fertilizer is only slightly more interesting than the soil one spreads it on: one of those super-simple, steady-Eddie, boring-but-profitable businesses every investor loves.

These are not normal times. On July 30, Uralkali, the Russian portion of the Eastern European export cartel that controls some 40 per cent of the world’s production of potash—the mined and manufactured salts containing potassium—declared its joint venture kaput, accusing its Belarusian partners of selling product on the sly, thereby pushing down market prices. Going forward, the Russians will pursue a volume-over-price strategy, using their position as the world’s lowest-cost producer of the crop nutrient to sell as much as they can, whenever they can, to whomever they can.

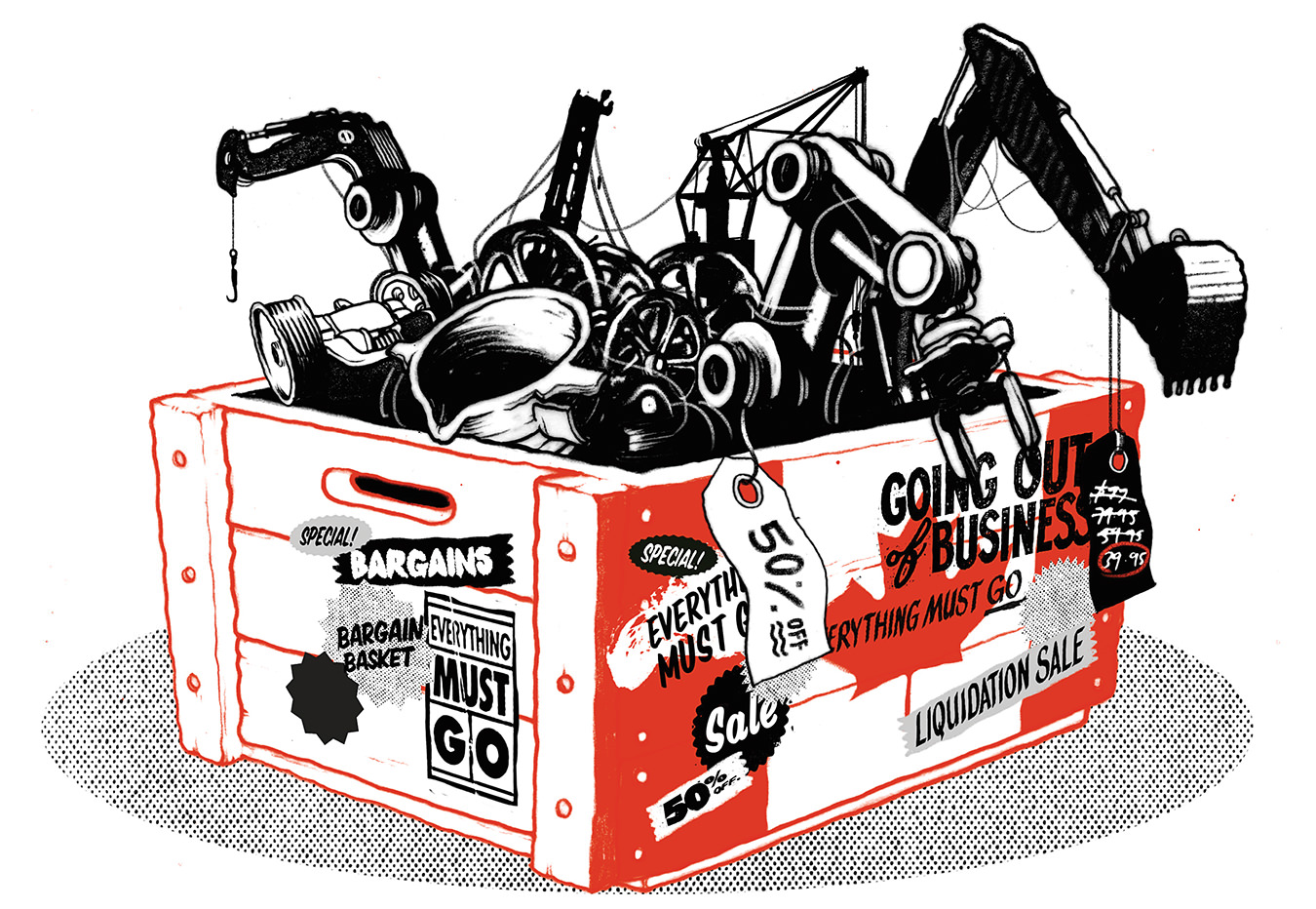

And in that moment, the fertilizer industry shifted from simple, steady, and boring to complicated, volatile, and more than a little dramatic—think le Carré–style thriller crossed with a Mexican telenovela, with a dash of Fight Club thrown in. Since the Russian announcement, there have been accusations and threats, trade sanctions and import bans, oligarchs forced to unload their stakes at fire-sale prices, high-level diplomacy between heads of state, and a CEO summoned to a cross-border meeting and then thrown into a KGB-run prison. What there hasn’t been, however, is an end to the acrimony.

Potash is big business, particularly in Belarus, where it supplies some 12 per cent of state revenue as well as a much-needed source of hard currency. But the mineral isn’t exactly small potatoes over here, either; BMO Nesbitt Burns notes that Canadian exports of potash have averaged about $459-million a month between July 2012 and July 2013. If the Russians follow through on their threat to bury the world in potash, that number stands to be a lot smaller. Little wonder that on the day Uralkali filed for divorce, the share prices of the big three North American potash producers (Potash Corp. of Saskatchewan, Agrium, and Mosaic Co., who collectively function as the world’s other potash cartel) took a beating; at one point, both Potash Corp. and Mosaic Co. stock were down more than 23 per cent.

Whether such events come to pass is another question. Cartels are the ultimate in profit-making power—the real-life equivalent of owning Boardwalk and Park Place, along with Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and Pacific Avenues at the same time—and rare is the CEO who breaks one up willingly. Indeed, some analysts have mused that Uralkali’s Dear John letter may be nothing more than a bare-knuckled negotiation tactic. By hitting its former partner where it counts financially, Uralkali can reconstitute its cartel on more favourable terms. If such a move happens to bleed its overseas competition or scuttle other producers’ expansion plans—well, so much the better.

Most investors ply their trade on the left side of the brain, using reason to study credits and debits, profit and loss. As the potash crisis proves, however, not everything in the market can be answered with logic. How, exactly, is the rational investor supposed to consider political risk? How does the logical investor protect against decisions made by oligarchs and tinpot dictators on the other side of the world? For every investor looking for an answer, there’s a farmer who doesn’t care.