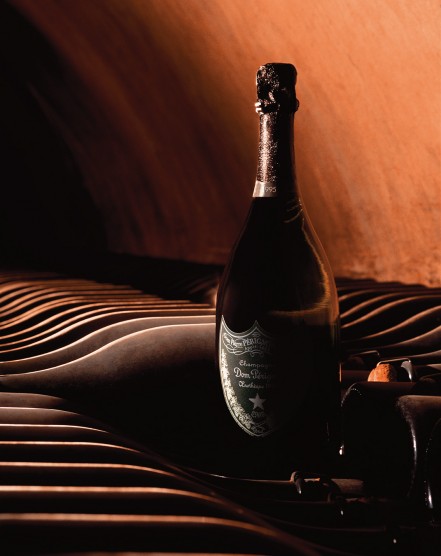

Vincent Chaperon at Dom Pérignon

Fizz whiz.

At 33, Vincent Chaperon looks his age—no older, no younger. He’s smartly dressed in a suit and tie, and looks like a whiz kid in the world of law or commerce. Instead, he’s a fizz kid, the oenologist at renowned champagne house Dom Pérignon.

If there’s an icon among champagne brands (and there’s some competition for the title), it’s probably Dom Pérignon—“Dom” as it’s casually called by people who drink it more than occasionally, or would like people to think they do. It’s the champagne that wears the prestigious name of Pierre Pérignon, the 17th-century winemaker monk who’s often portrayed as the founding father of fizz.

As with many legends, Pérignon’s is a blend of truth and fiction. The cellar master at the Benedictine Hautvillers Abbey near Epernay, Pérignon was rumoured to be blind and, as a result, to possess enhanced tasting acuity. After extensive experimentation, he sipped his creation and experienced the sensation of hundreds of bubbles bursting in his mouth like pinpricks, and he supposedly exclaimed, “I am drinking the stars!”

Much of the story is fiction, constructed centuries later. Sparkling wine was being made routinely elsewhere in Europe well before Pérignon’s day, and there’s no reliable evidence that Pérignon was blind. But he may well have improved on common vineyard practices by reducing crop levels and by using selected parcels of vines for higher quality wines. He may also have created the innovation of sealing bottles with cork, rather than the wooden pegs wrapped in oil-soaked leather that were commonly employed.

And whatever the proportion of truth to fiction in the blend of the Dom Pérignon story, the master left big sandals to fill. But judging by the results, Chaperon, along with Richard Geoffroy, the chef de cave, are more-than-able heirs to Dom Pérignon, performing together the tasks he carried out alone.

Vincent Chaperon in a vineyard.

Chaperon evokes the achievements of the monks of Hautvillers and expresses his admiration for the way they advanced winemaking. “The only way to understand wine,” he says, “is to be truly dedicated—you have to live through many vintages. And the monks had the time, you know?”

It’s a statement that leads to the obvious question: how does a young man of 33 land a senior role at Dom Pérignon after only five years with the company?

Chaperon is a native of Bordeaux, where his grandmother owned a winery in Pomerol. He studied oenology at Montpellier and, after graduating, worked first in Chile for Concha y Toro and then back in Bordeaux, in Saint-Émilion and Sauternes. But he didn’t want to stay in Bordeaux, which he says he found “a bit closed”, so he headed for Champagne. There, he started working at Moët & Chandon. (Moët and Dom Pérignon are both part of the luxury wines and spirits company Moët Hennessy.) He didn’t expect to stay long; Champagne’s climate was too cold, and it was too far from the sea. But he stayed on, and eventually became part of the Dom team.

It’s the team aspect that Chaperon emphasizes, with him and Richard Geoffroy working seamlessly together. Geoffroy, who has been with Dom Pérignon since 1990 and been chef de cave since 1996, represents experience and maturity. Chaperon refers to him more than once as his mentor. Chaperon, for his own part, says he represents innovation and energy: “I challenge everything.”

How do you challenge and innovate when you’re dealing with a brand as iconic as Dom Pérignon? Can you make radical changes in any aspect of it, and get away with it?

“The only way to understand wine,” says Chaperon, “is to be truly dedicated—you have to live through many vintages. And the monks had the time.”

No, you can’t. There can’t be any “brutal change” from one vintage to another, Chaperon says, but there can be “gentle pressure”, change in “a slow, continuous” way. It’s important to keep a sense of balance, but there has been movement in the Dom Pérignon style since the 1990s.

And, he stresses, it’s a strength of Dom Pérignon that it is evolving. “If you have good people, they will move it in the right way. Our team is made up of people who have a lot of experience, and others who are younger,” he says. “To go on improving after 300 years, you need the good people. Our team is full of energy, as it is well balanced between the new ideas of young winemakers and the knowledge of more experienced ones.”

What Chaperon talks about—the evolution of style—is intrinsic to the history of champagne. Only 200 years ago, champagne was not the bright, light straw colour it usually is now, but a light pink-brown, sometimes referred to as oeil de perdrix, or “eye of a partridge”. And it was more often than not quite sweet, with the level of sugar calibrated to the specific export markets; the English tended to like their champagne dry, while the Russian aristocracy preferred a sweeter style. So Chaperon is not talking about radical shifts in style, but subtle changes.

One of the features of Dom Pérignon that facilitates change is that it’s always vintage dated rather than, like most other champagnes, a blend of wines from two or more years. Blended champagne can be made to a consistent style, year after year, as winemakers suppress the idiosyncrasies of individual vintages. A year when acid development was low can be corrected by blending in wine from a year when it was higher.

But Dom Pérignon, being a vintage champagne, varies from year to year according to the conditions of the growing season. In some years, only the rosé might be made, in others only the white, while in yet others, when the overall quality of grapes is judged to be too low, no Dom Pérignon at all is made.

Vintage variation, rather than the consistent style and profile of non-vintage champagnes, means that there must be more leeway for change. A Dom Pérignon aficionado expects the same style, but not exactly the same flavour and texture profile, vintage after vintage.

Chaperon stresses the importance of terroir, but in a less dogmatic way than many French winemakers. Dom Pérignon is a blend of chardonnay and pinot noir—there’s no pinot meunier, the third permitted champagne variety—and it draws from vineyards in a total of nine villages, four growing chardonnay and five growing pinot noir. It’s important, he says, to understand, respect, and retain the diversity and individuality of the vineyards.

Chaperon strikes a refreshingly careful balance that recognizes the significance of both terroir and the winemaker. “Dom Pérignon is a synthesis that respects terroir, but we also want to express a vision.” He gives weight to the role played by Geoffroy here. Geoffroy, he says, is atypical in the world of wine in that he takes an artist’s approach to it.

“The grapes are like raw material to a sculptor. You have to know how to transform it, how it will react and change, and the first thing is to have a perfect understanding of the terroir. It’s a matter of understanding the diversity, as the monks did.”

Chaperon thinks that winemakers in Champagne have been losing their understanding of terroir. “They know this and that. They know the best parts. But I think we lost it a bit.” With the new tools available for mapping vineyards, a more precise level of understanding is possible. Still, Chaperon says, as a vintage champagne, Dom Pérignon “is not something we can make by a recipe. A big part of the job is trial and experiment. We have to rethink everything.”

It’s a provocative message that may not, perhaps, sit well with some Dom-lovers, even though they’re accustomed to their champagne varying a little from vintage to vintage. But change, says Chaperon, will be gradual, “like adding a small touch to a picture”.