-

El tango no está en los pies, está en el corazón—The tango is not in the feet, but in the heart.

-

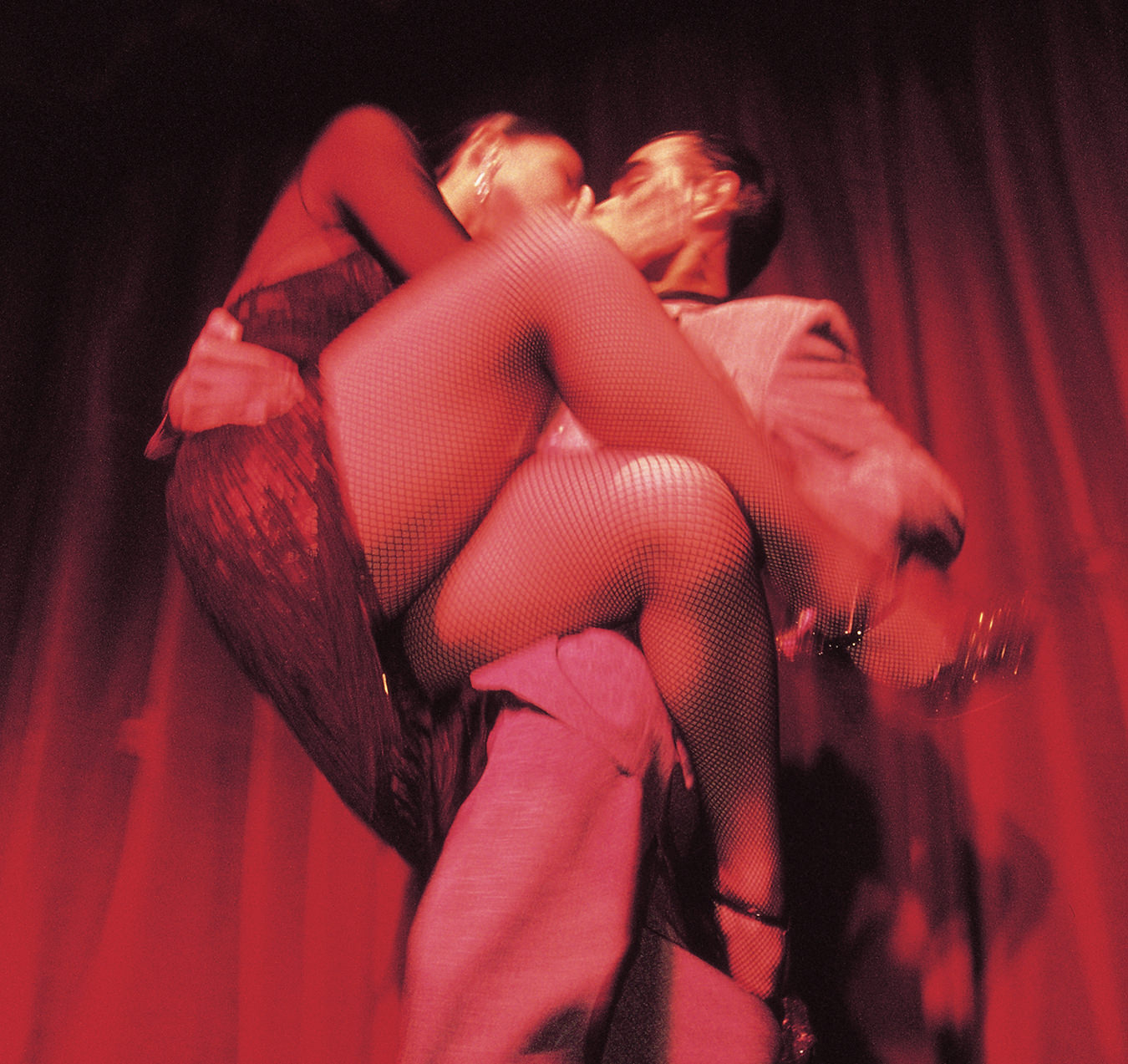

A glance or a fixed stare becomes part of the silent language between dancing lovers.

-

Gravestone of Carlos Gardel.

-

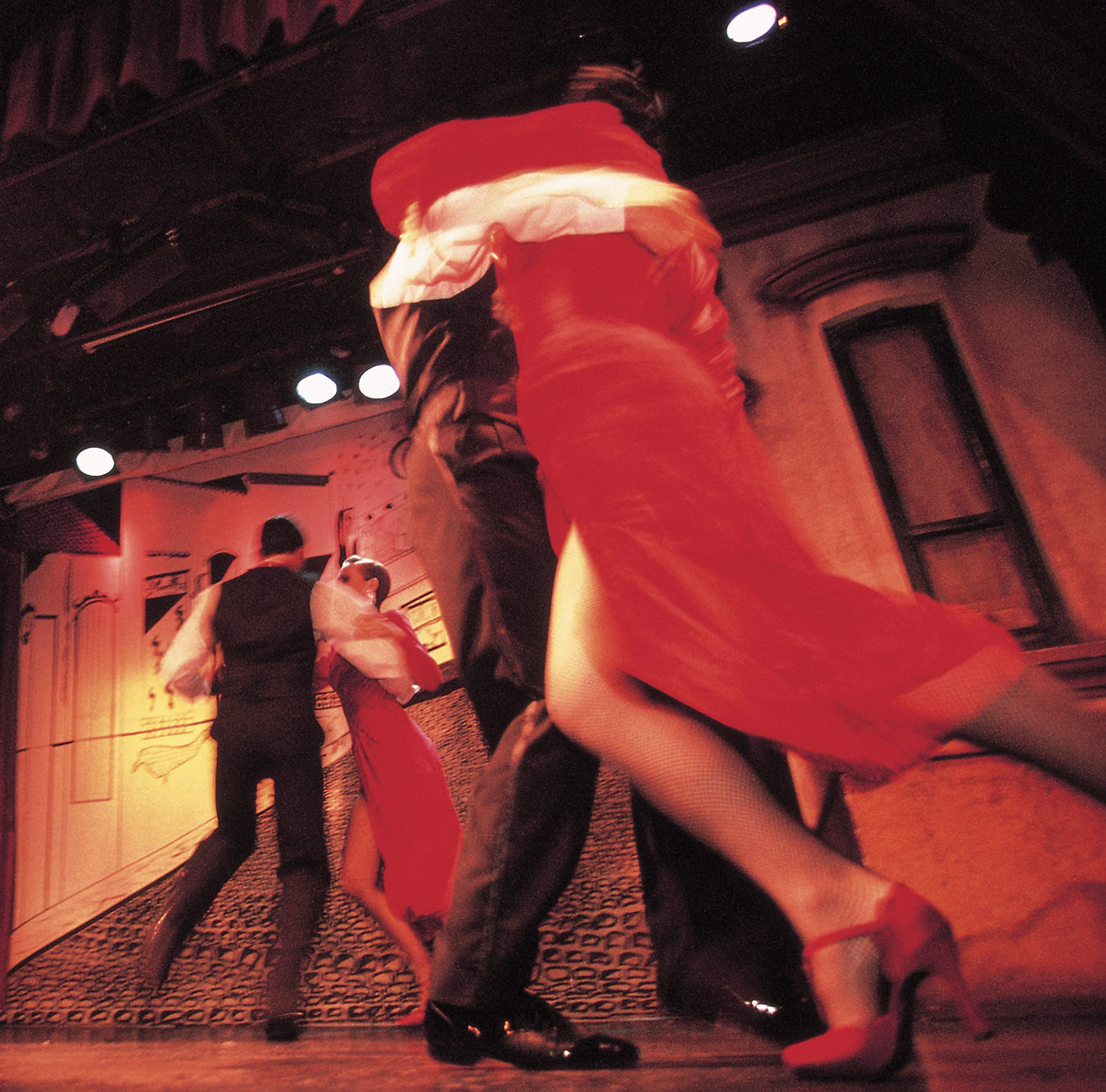

The scene at Tangueria “La Ventana”.

-

Biyi and Osvaldo backstage at Tangueria “La Ventana”.

-

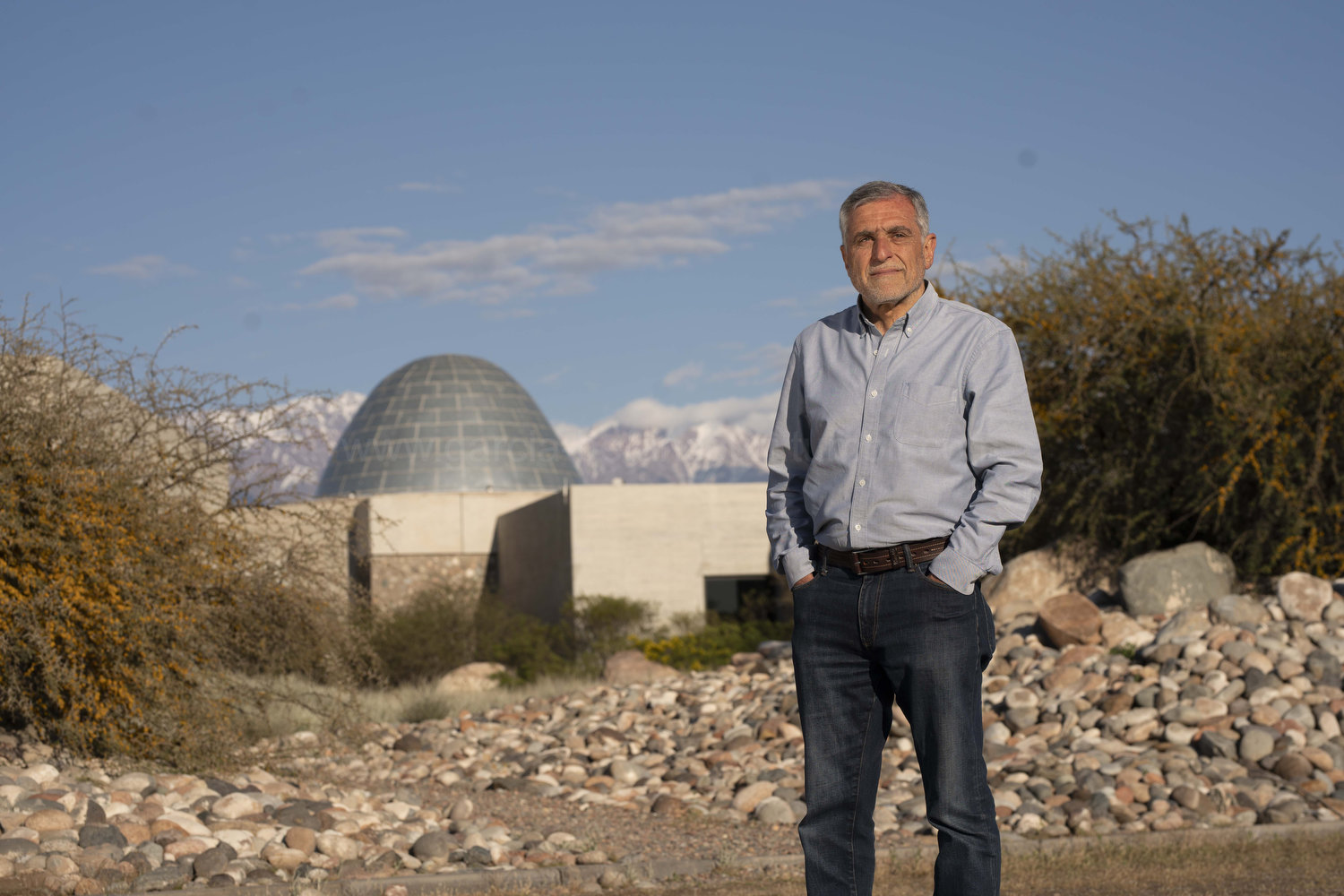

Carlos and Alicia, world renowned tango dancers, in their old, familiar studio.

-

On stage at Tangueria “La Ventana”.

-

The bandonéon was imported from Germany— mid 1880s.

An Affair with the Tango

The history and fierce romance of Argentina's national passion.

Twelve decades ago in Buenos Aires, it began. A large, displaced, mostly male immigrant population founded one of the Argentines’ own ambiguous self-definitions: a Spanish culture that spoke Italian, emulated the French, and wished it was English. Argentina was only going to be temporary, or so they hoped, in vain, as they pursued their elusive fortunes. This isolated cultural milieu produced the anxiety over identity that has been the denominator of the Argentine psyche and is crucial to understanding the roots of the tango.

With fifty men to every woman in the Argentine port city of the 1880s, men danced the tango with each other at bordellos, practicing new steps, perfecting older moves and defining a distinct pecking order each night. The tango was the winnowing process, the best and strongest dancer reaping the first woman who descended the staircase that evening. It was choreographic foreplay and it was more. Because she might teach him the newest status steps, if he pleased her on the dance floor…and upstairs.

In this archetypal tango the woman would submit—but the man might be undone—with the subliminal understanding that no one would be the wiser. The dance disguised the broken, disillusioned woman as a glamourous and powerful femme fatale in stiletto heels. And guarded behind the confident facade of the fedora-sporting pimp was the melancholy cynic and failed romantic.

Tango thus expressed the exquisitely poignant pleasure of the choreographed dangerous liaison. It was in-evitable that Argentina would ban it. And equally inevitable that, like Prohibition in the northern hemisphere, outlawing it would make it more desirable and exciting—compulsory for the stylish. Rich, upper-class Argentineans began learning the dance covertly and teaching it to friends. And when they travelled to refresh their cultural souls in Europe, they took it with them—although in the early 1900s, it proved too much for the Continentals. In Paris, still in the thrall of La Belle Epoque, the dance’s raunchy nature was too overt. But by 1907 in the slightly more torrid Nice, that casino town in southern France on the Grand Tour for royalty and the wealthy, the tango had been tidied for admission to Society’s ballroom. The dance was transformed from waterfront prostitute to Proustian courtesan, its sensuality lashed with a soupçon of that enticing pheromone, depravity.

There was even a Tango Championship Contest that year and by 1909 it was included in the Paris International Dance Competition. The City of Lights was beguiled and by 1912, the tango, having become seriously fashionable, was creating a sensation at all of France’s social hot spots. An apoplectic Parisian cardinal attempted to force France to emulate Argentina and ban the dance while also pressuring Rome to deny absolution to those who performed it, but to no avail. A year later, the tango overwhelmed England, with an orgiastic stampede at every hotel that held a “Tango Tea”.

On this wave of enthusiasm the briefly but incandescently famous Castles arrived to ensure the tango’s eternal international acceptance. Vernon Castle was British, Irene American; they had perfected a dancing act which wowed France in those ominous days immediately before the Great War, introducing such steps as the Castle Walk and the Fox Trot to rapturous audiences. Discovering the tango, they added it to their repertoire of dazzling footwork and took it back to America.

But the Castles—whose reputation and popularity made them arbiters of the rules of dance—were concerned about the tango. Writing in their 1914 book Modern Dancing, they complained “nearly all teachers teach it differently” and that it must be “standardized”. They disputed the reputed one hundred and sixty steps in the Argentine tango and consoled their readers by stating categorically that “knowledge of six fundamental steps is quite enough”. The debate was but the opening salvo of a battle over the soul of the dance that remains to this day. But the Great War rendered the argument irrelevant.

Throughout the decades there were many players whose mastery of the bandonéon made them renowned. But none had greater impact than Astor Piazzolla.

As Europe proceeded to dine savagely on itself, an ambivalently neutral Argentina began to turn inward; and as society changed, the dance would reflect it. The “Golden Age of Tango” (as defined by many of the Guardia Vieja or Old Guard view) was inaugurated in 1917 when Carlos Gardel recorded the song “Mi Noche Triste (My Sad Night)”. It was a timely innovation that married the music to poetic lyrics, articulating and deepening the expression of passion and pathos. Gardel said he took the tango “from the feet to the mouth”. Dancing became distinctly less important as the people of Argentina (with its new creeping isolationism) listened to their own tragic stories unfold poignantly with each new song. The tango mirrored the fatalism and melancholy of the nation’s changing mood—a mood that would be perpetuated and exacerbated for the rest of the century and beyond, sometimes with politically horrendous consequences. At the centre of this new form of tango, the man who recorded “Mi Noche Triste” was an artist of historical import.

Carlos Gardel was to Argentinean tango what Elvis Presley was to American rock and roll. Possessing a warm, expressive baritone voice and powerful marketing skills, appearing impeccably dressed, with a dazzling smile and flashing eyes, “Carlitos” became the exemplar and epitome of the genre. His tours of post-war Europe were huge successes and his talent and career took on mythic proportions in Argentina. (This is cultural irony at its best, as Gardel, in addition to hiding his illegitimacy and birthdate, also covered up any evidence that he was born in either Uruguay or possibly the south of France.) And like other myths whom fate perpetuates in the world’s memory—James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Lawrence of Arabia—he was to die dramatically, in a plane crash at the height of his career, at the assumed age of 45. Carlitos’s power remains undiminished today. Hearing one of his classic recordings, a standard reaction of Argentineans is: “You know, he sings better every year.”

In 1921, Rudolph Valentino made his starring debut in the celebrated silent production of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, playing an habitué of the Parisian pre-war tango halls who becomes a war hero. The film’s opening tango scene electrified audiences and the dance became Valentino’s trademark, before, like Gardel, he died in the spotlight of fame, in 1926.

But the Valentino tango resurgence only hastened its embalming; the Castles finally got their wish. Ballroom dancing, having integrated the dance into establishment routine, started codifying it in 1922. The result was that within three years, the northern hemisphere tango had maintained its elegance, but was rendered increasingly static by mortising the dancers into officially approved steps and (by Argentinian standards) a pseudo-passionate attitude that was pure pose.

Meanwhile, in Argentina, the lyrical emphasis on the tango gave rise to another variation and another star, this time emerging from the unique instrument that was and is inseparable from the dance and the song. Tango’s truest instrumental voice comes from a smaller relative of the accordion called the bandonéon. It was imported from Germany during the wave of immigration—probably in the mid 1880s, the era where our story began. It could sigh, cry and weep—the always-leashed Argentinean complex of emotions. Throughout the decades there were many players whose mastery of the bandonéon made them renowned. But none had greater impact than Astor Piazzolla.

As a young man in the early 1940s, he was playing and arranging for Anibal Troílo’s tango dance band, arguably the best of all time. But by 1950, there were charges that the staleness to which the tango had succumbed in the north was equally true of the south. The tango as a vital cultural force was dying and the death of Eva Perón in 1952 accelerated this sense of loss. Piazzolla began looking for life in other musical genres.

He looked to the United States and embraced another indigenous musical art form with equally disreputable beginnings, becoming the matchmaker for Señor Tango and Sister Jazz. Piazzolla was determined that this innovative fling should not be an experimental one-night stand. Dissonance, chromaticism and improvisation aided the love match. Of course, these innovative violations startled and angered his conservative compatriots in the mid-’50s. “That’s not tango!” they stormed. You couldn’t sing to it nor dance to it. But the new jazz mistress proved intractable and she breathed new life into the tango. It would take two decades of struggle and Piazzolla’s own exile touring in Europe and the United States to universal accolades before the new sound would be grudgingly accepted in Argentina. By mid-century tango’s bifurcation into two entities—music (with or without lyrics) and the dance itself—had intensified, with the evolution of the music matched by the inevitable transformation of the dance.

The dance becomes an intense, if stylized, physical liaison and a glance or a fixed stare becomes part of the silent language between dancing lovers.

For example, a classic tango hold is immediately ambivalent. It couples each dancer into a synchronized thigh to abdomen embrace but demands that the always-erect back will force the chest away, thus ensuring that only the carnal is insistently emphasized and the problematic heart kept distant. Thus, the dance becomes an intense—if stylized—physical liaison and a glance or a fixed stare becomes part of the silent language between dancing lovers. But should those looks be directed at someone other than the partner—all being fair in love, war and tango—a straying eye can be thwarted by an abrupt turn, an ochos picante step or a tighter cinching to the other’s waist. The tango can ignite romance. Or end it.

It has always been a myth that there is a single type of tango. Those familiar only with the ballroom stylings are surprised to discover within Argentinean tango: Guardia Vieja (Old Guard), Milonguero (Tango Club), Salón or Academia, Nuevo Tango (New Tango), Tango Orillero (Out of the Norm Tango), Show or Export Tango, Tango Liso, (a basic style stripped of any fancy footwork), and many others vying for and claiming legitimacy. And in Buenos Aires, many bewildering sub-categories take the wrangling over subtle nuance to even greater heights. For example, one of the finer points of discussion might be how a woman could effectively “back-lead” her partner without him noticing, or whether you can “attend” to the lyrics of a tango song while dancing (traditionalists have never accepted two tango cultures, refusing to dance to anything with lyrics) or the perfected degree of adoquín or “cobblestone” in your dance (derived from the way one walks on cobblestone streets).

If you were to drop in at a Milonga, a tango club where dancing starts around eleven or midnight and goes to four or five in the morning, you would see variations of a “close style,” a vertical missionary position, if you will. It is an intimately affectionate cradling between partners sometimes bonding from face all the way down to shins and feet with the leading hands held close to the chest. (Seeing a protective grandfather teaching his granddaughter in this tender way at two in the morning before the rest of the appreciative family is perfectly socially acceptable. What better way to learn the steps?)

“It’s like seeing legs caught in a blender,” someone exclaimed after seeing one of the tango productions that toured world stages in recent years. Forever Tango and Tango Argentino (nominated for a Best Revival of a Musical Tony Award in 2000, on its return after a decade and a half) are potent, electrifying shows, drawing tango tyros to dance studios around the globe. And for seriously addicted tangueros, there are package tours to Buenos Aires.

The story of the tango is one of steps and styles, passion and pathos, institutionalism and innovation that has, through twelve decades, moved from country to country and hemisphere to hemisphere—always returning to native Argentina. And yet, for all of this, the secret of dancing the tango is simple and unchanging. Experienced and truly sublime performers explain how they dance from an inner stillness, where body and mind are absolutely quiet. It is a sense of focus that bares the core and soul of tango. You can ache for old or lost loves, fire up current infatuations or a longterm relationship and, perhaps most important, enhance the emotion stimulated by your partner of the moment—even if that person is a stranger.

And it confirms this old Buenos Aires wisdom: El tango no está en los pies, está en el corazón—The tango is not in the feet, but in the heart.