Off the Shelf: The Real Lives of Imagined Others

Books by Leslie Jamison, Ben Lerner, and Jenny Offill.

There’s no end to the catalogue of ways humans suffer, and manage to inflict suffering: illness and injury, psychic suffering, material deprivation, heartache, loneliness, catastrophe, separation, history, bad luck. There are long and venerable schools of thought—from Buddhism to Schopenhauer—staking the claim that human existence, when considered and weighed up honestly, is nothing but suffering. By some accounts, civilization is simply the encoding of laws limiting the ways each of us can inflict suffering in pursuit of the fulfillment of our own (uncontrollable and unknown) desires. But this is a stark, reductive view of humanity, isn’t it? Infants and toddlers, dogs and apes, deer and crows have been shown to have a moral sense. Even hockey players. All of them will attempt to comfort others when those others are perceived to be in distress. And cultures all over the globe, it turns out, have worked up versions of the golden rule “Do unto Others as You Would Have Done unto You.” So we could see our ever-metastasizing and hyper-vigilant lawmaking as a second-order codification of some more deeply embedded command or exhortation to at least not bash each others’ heads in. I’m trying to get to the notion of “empathy”. This internal barrier to outright cruelty might itself include the first seeds of a developed empathy. This nebulous, nerve-ending imperative to project our very Self into the Other in order to check our baser impulses has to fall within the definition of empathy, doesn’t it, if only at its thinner, less imaginatively demanding end?

Most of us have mastered those basics. Instead of just disposing with the human who has the coveted cashmere pullover, then walking away with it, we’ve learned that a compliment and perhaps inquiry as to its place of purchase instead of stealing lessen the anguish felt by both parties. It’s when the call to empathize gets more complex, or runs into clouds of interference, or simply falls way down our list of what seems practically doable, that we find routes of least resistance out of the situation. We walk by. Head home. Not bothered. Or only just a little.

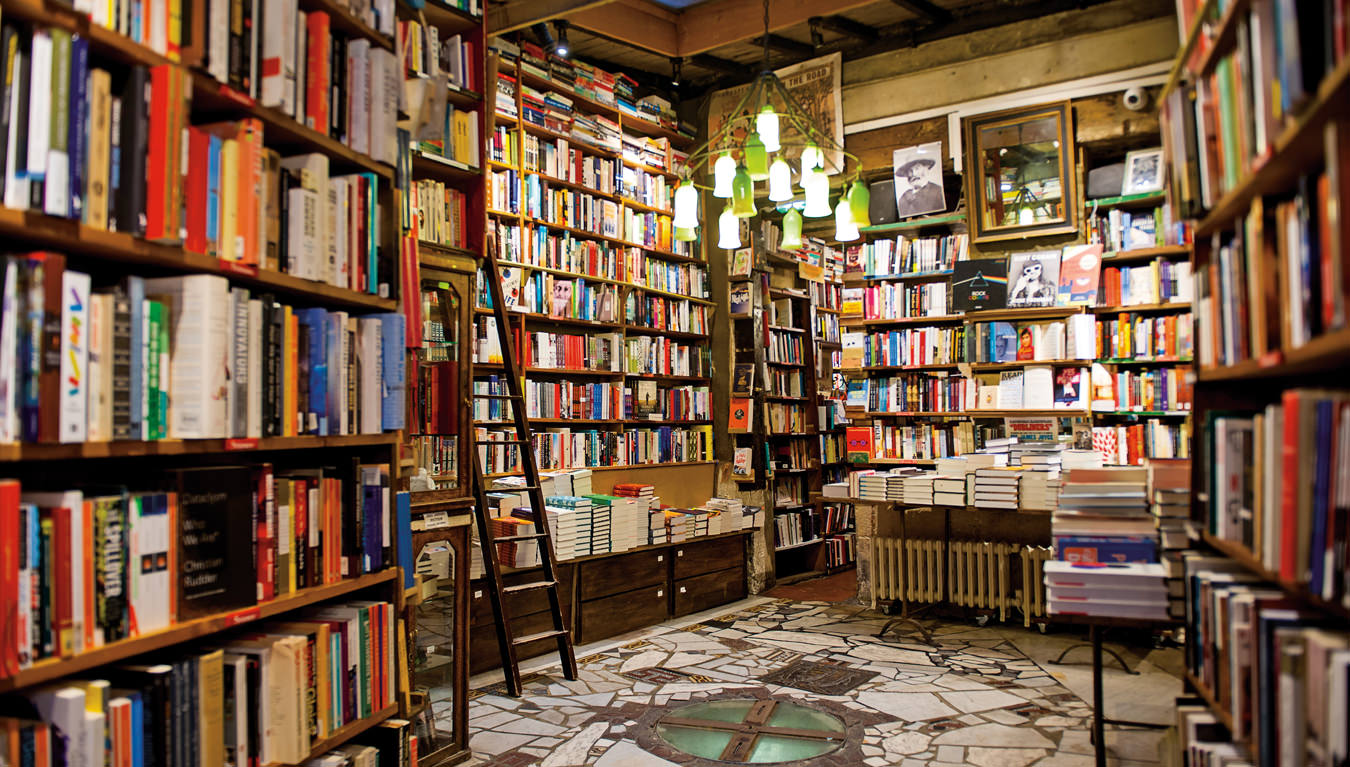

Fortunately, we have carved out a space in the social body for others who are. Take a bow, novelists. It’s what they do. They spend their lives projecting themselves deep inside the lives (and minds) of others. And it does not matter, even a bit, that these “others” are fictional beings who never lived and won’t ever. Or, the formula could be upended: fiction writers bring the inner lives of others out into the light of day. We build our capacity to imagine another (real) person’s inner world by reading the imagined inner worlds of (fictional) people.

Leslie Jamison is a young writer who perhaps didn’t quite believe the veracity of the sorts of claims I’ve just made for fiction. So she decided to test herself. The Empathy Exams is a riveting collection of essays (her second book, following a novel, The Gin Closet) that dives into this murky human terrain with a skeptical, resistant intelligence paired with a fiery commitment to fully feel the contours of her subjects’ most entangled and baffling situations. Picture an anthropologist freed from the imperative to pursue objectivity. Or a memoirist who’s decided everyone else’s lives are her subject matter. Or an investigative long-form journalist who doubts her own position and point of access to what we’re meant to take as “facts”. Jamison is all of these, and more, often inside a single passage.

Novelists spend their lives projecting themselves deep inside the lives (and minds) of others. And it does not matter, even a bit, that these “others” are fictional beings.

The collection’s opening autobiographical essay—bearing the book’s title—sets the bar several storeys high, while operating simultaneously as a display case of formal marvels deployed through the book’s subsequent pieces. We see in this essay the impossible double-bind Jamison will set for herself over and over. An acceptance of the absolute necessity for, alongside a recognition of the near futility of, immersive empathic imagination.

“My job title is Medical Actor. That means I play sick,” she begins, and she means it. “Medical students guess my maladies. I’m called a Standardized Patient, which means I act toward the norms set for my disorders. I’m Standardized-lingo SP for short. I’m fluent in the symptoms of preeclampsia and asthma and appendicitis. I play a mom whose baby has blue lips.” After performing their examinations, these medical students are evaluated by Jamison on, among other things, whether and how much they “voiced empathy”. Meaning, did they say the right things that would indicate they have actively felt concern for their patient. Add to this structural gamble on the observable surface the second layer of enacted empathy going on, that of Jamison’s performance of a person in pain, or otherwise suffering. Granted she’s not a method actor, just a writer trying to pay her rent, but she’s still given a 12-page “script” complete with personal history, family illness, existing conditions, and levels of self-awareness spelled out in detail. She’s expected to be these patients for $13.50 an hour. Now add again another layer, the so-called “real” life being lived concurrently with the work situation. Jamison gets pregnant, then decides to terminate. She walks us through the lead-up to her abortion in frightening detail. The shifting sands of sadness, self-doubt, frustration, and the expectations laid at the feet of her partner, the entire minutely inspected, constantly second-guessed dark rainbow of one individual’s emotional response to one important life decision. Jamison is not without a scalpel wit, a droll tone when appropriate, and a painter’s eye for subtleties of shading and colour. But the wonder of this collection is its unwavering seriousness. Jamison wagers everything on humanity’s capacity for care, so even when she sees us failing to do so, or catches herself making it up, or missing the mark, the vigilance of her prose becomes its own mark of deeper attention to suffering.

Ben Lerner’s first three books were much-acclaimed collections of poems; his fourth was the surprise critic’s-choice novel Leaving the Atocha Station. This new one, 10:04, appeared last year riding the buzz, as they say, of a large advance and stellar credentials. That usually means the (lit) world silently wanted it to fail. Or wanted it to succeed but would’ve been happy if it failed. Poor lit world. It’s a wonderful book. All the sly, mordant, hyperaware intelligence and metafictionally exposed pilings are back again, but the ache of human hope and psychological frailty add new layers of risk to 10:04.

We’re dropped in the middle of Ben’s life (our narrator, and a fictional version of the author); he’s a newly successful novelist whose friends all wish he’d go back to poetry. He’s been diagnosed with a possibly (not likely) fatal cardiovascular condition. He’s the best company you’d ever want for an ill-advised poolside ketamine trip in Texas. He wants his life’s endeavours and scrapings to mean more than zilch when weighed on the scales of History. He knows his Whitman and has a thing or two to say about proprioception, about Time, about Capital.

The novel’s title is taken from that ’80s cultural touchstone Back to the Future, referring to the moment lightning freezes the hands of the town’s clock tower. But the book’s pop quotient is supremely blended with the more rarefied, and at times despairing, air of the contemporary art world. Lerner is brilliant at digression. Verbal and physical, wandering galleries and museums, falling into a writing spell at Marfa, Texas, or walking Manhattan with his best friend who’s asked him to donate sperm so she can be a mother. The bulk of 10:04’s action is the action of pointedly modern anxieties, grim asides, and grave reckonings that form Ben’s interior theatre.

We’re dropped in the middle of Ben’s life (our narrator, and a fictional version of the author); he’s a newly successful novelist whose friends all wish he’d go back to poetry.

But don’t cheat yourself by thinking this novel is another Ivy-educated navel-gazer’s mental gymnastics. This book’s unique formal compass is always finding its true north at two opposing points, phasing between the two. The subjective “interior” proves to be this novel’s way out, toward others, and the many. Toward unimagined potentialities.

Any mental health professional would likely consent to the idea that real empathy between intimates must be built on trust. Jenny Offill has pulled off a startling inversion of that idea in Dept. of Speculation, a novel stripped to such bare bones they could be called bleached. We see a lot of page on each page. Written in epigram-sized entries barely more than a sentence, the novel somehow gives full-to-bursting expression to the pain and bewildering disenchantment that can befall a marriage rocked by infidelity and a barely perceived turning away. The inversion occurs once we’ve taken on board how very much of the narrator’s emotional life we, as readers, have been entrusted to see and feel fully. In some ways even at the expense of the character we’re caring for. The trust and interchange that’s been vacuumed out of the narrator’s life Offill has magically gathered up and set down before us without our having prepared for it. It’s a magnificent switch-up that keeps us at uncomfortably close proximity to a “stranger’s” heartbreak while simultaneously gazing at proceedings from a place of clinical remove. Even at the level of pronouns, this ambivalence is hard at work on us. The narrator herself has begun referring to her life’s entangled triad as though they were in a play, or simply dolls housed in a grim triangle: “Husband”, “Wife”, and “Girl”. As she talks herself through the desertification of her own life in this self-protective argot, we can only dissolve at the storm of fury and sadness being held in abeyance.

I’m not quickly given to making needlessly mystical claims—or outright religious ones—on behalf of literature, but it would be tough to argue there isn’t something staggering about the more resonant phenomenological loops set up by fiction. I also don’t like our knee-jerk resorting to the claims of science in order to validate anything and everything from “mindfulness” to “generational trauma”. Nonetheless, as metaphor if nothing else, consider the story of mirror neurons, those bitty bits that cause our brains to “copy” or in some mental sense “live out” what we’re watching someone else do. That’s all freaky enough, if it stopped there. But the same transformation happens in us while reading of someone who isn’t, in any material sense, there. We actually confer on them an interior world sometimes orders of magnitude more impassioned or imperilled than our own. And it moves us as though it were in fact our own.