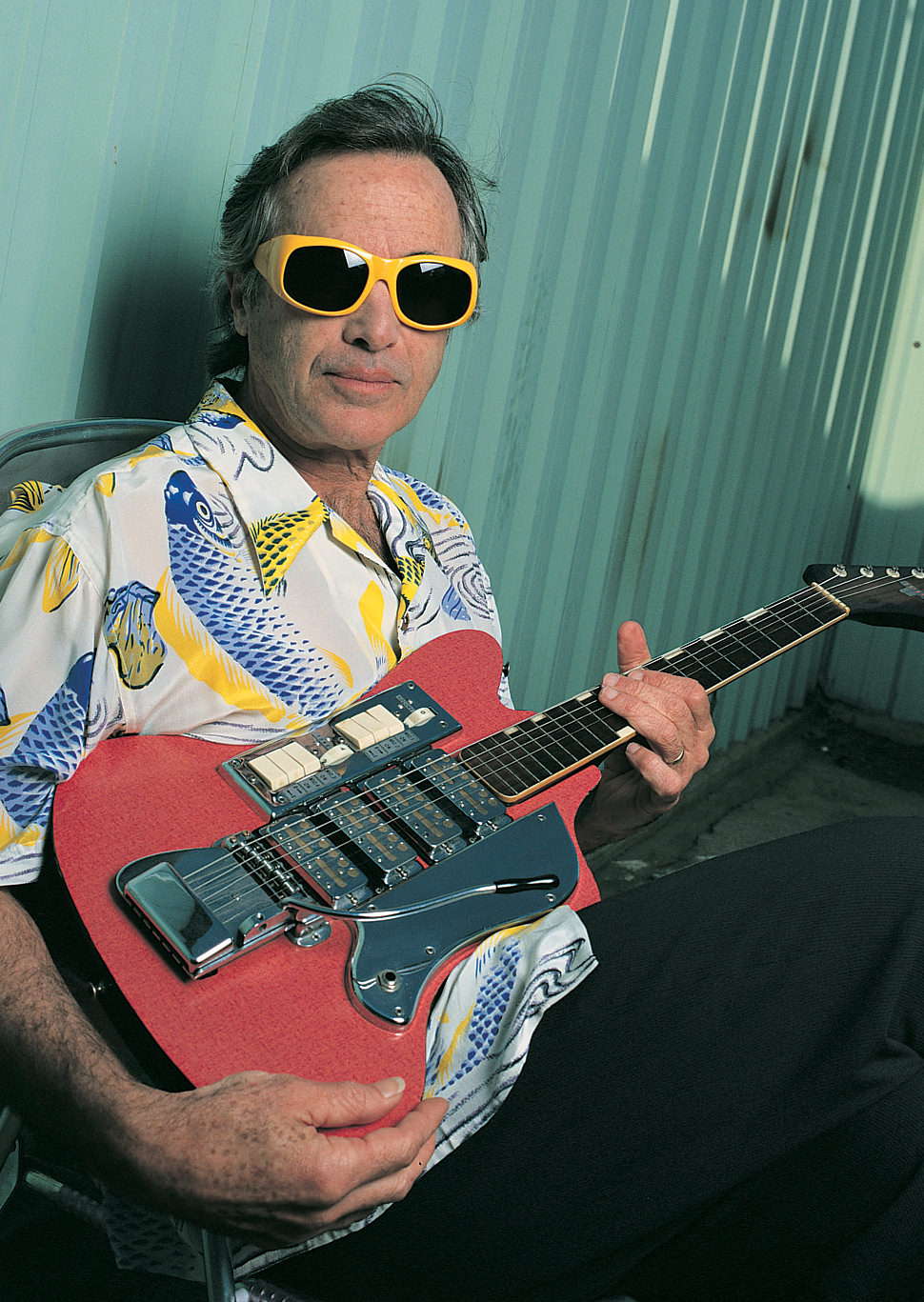

Ry Cooder

Ry's sense of humour.

He is a music archaeology department all to himself, having played with and learned from the very best in the world. Be prepared to spend several hours if you invest at all in examining his discography, and even then, you’ll likely wind up seeing a few films, too. Ry Cooder is happy to talk about his latest project, called Chávez Ravine, something that was “a long time coming. So long, in fact, I didn’t really anticipate it happening. The great Don Smith constructed it.”

Cooder is steeped, deeply, in many American music traditions, and strains within those traditions. “Your brain kind of cooks the music. You need to learn and absorb in a molecular way, not an empirical way.” In the case of this record, it is pachuco music, and a little hybrid called pachuco boogie. It all came out of the late 40s and early to mid 50s, from radio theatre, and from the music of the canteens and bars in the area that was demolished to make room for Dodger Stadium. Safe to say, no one asked the locals when the decision was made. “Pachuco barely got recorded,” says Cooder. He went out and found two singers who had practiced it back in the day, Lalo and Tosti. “The true uncontaminated voice, simply a throwback, totally authentic” is how Cooder describes them. The singer would sit on a high stool, a multi-directional microphone above, all the musicians seated in a circle around the stool. Cooder says “It was the great fortune of making this record to try to build a context out of nothing. You see these things historically, because it is gone. And the musicians, they played into the music. These days, people tend to overplay; salsa turned into show music, you know.”

Mr. Cooder knows something about this, of course. He would not readily accept the title of “Founder”, so let’s call him the instigator of the Buena Vista Social Club, a culmination of decades of musical searching on his part, and decades of musical genius lying in a state of disuse in Cuba. A marriage of true temperaments. “It was like going to Harvard for a post-graduate degree and having Oppenheimer as your physics teacher,” Cooder says. That phenomenon, which lead to a massively popular recording, also lead to a Wim Wenders film, and many discs by some of the members of the Club. It all amounts to sharing, on a massive scale, some of the “hidden gifts and hidden problems” of playing (and by extension listening to) music that is “all about space. I learned there to move the music around, and to do that you need to know the stuff.” This comes from a musician who has played on many dozens of albums over the years, studio work with Van Morrison, The Rolling Stones, and many many others, including a little bottleneck guitar work on Gordon Lightfoot’s cover of “Me and Bobby McGee”.

Cooder has collaborated on albums, usually an exploration of the differences and similarities between distinct cultural sounds, and instruments. He has over a dozen of his own recordings, including such exploratory work as Chicken Skin Music and Bop Till You Drop, along with several film soundtracks, to his credit. But it has never been about fame and fortune, but rather, about music. Pure and not always simple. The next project he’s rolling over in his mind is an album of material that was typified by the great Merle Travis, who wrote the immortal “Sixteen Tons” among many other songs. “It is music that people would consider totally under the radar today. Songs about down and outers, the southern border areas, all the music that we could only hear on the radio. And I wouldn’t touch Travis himself, he stated the case of these people he wrote about. I can’t go there; he was Beethoven-like.” A little silence, and then Cooder murmurs, “Talent is what it is.” Can’t argue with that, especially when it comes to Ry Cooder.

Photo courtesy of Warner Brothers.