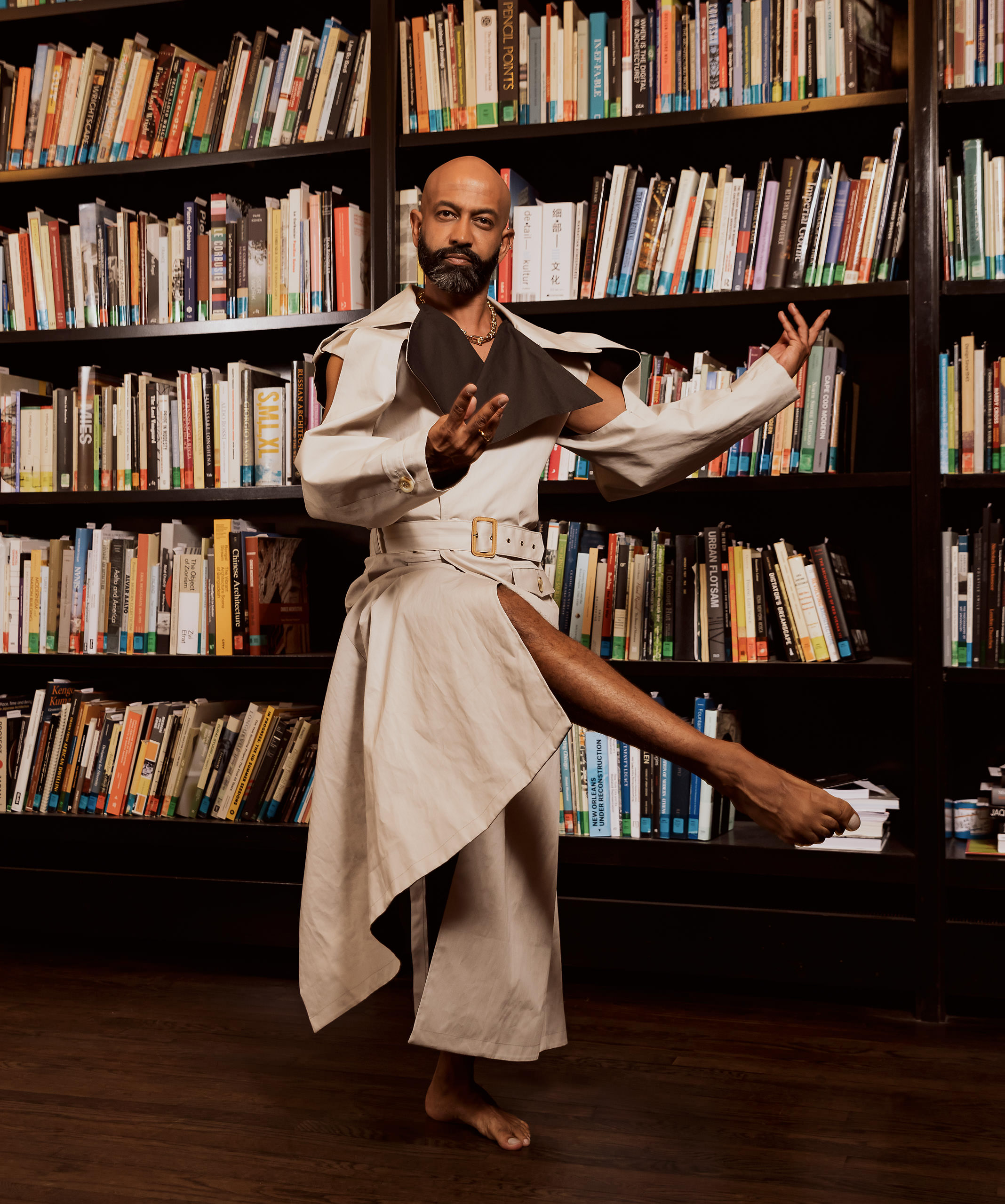

Jamie Oliver

There's something about Jamie.

Jamie Oliver is sitting in a leather armchair at Fifteen, the London restaurant he opened in 2002 to train disaffected youngsters, sipping a beer and looking very comfortable in his own skin. He is in an ebullient mood. This isn’t because he has a new book coming out or because his steak knives, bruschetta toppings, and acacia wood cutting boards are selling well on Amazon; it’s not even because his Food Tube channel on YouTube has gained another few thousand hits. No, his chirpiness is political. It stems from British Prime Minister Theresa May’s failed attempt to win a parliamentary majority in the previous week’s general election, forcing her to abandon many of the most controversial policies in her platform. One of those was a plan to scrap free school meals for four- to seven-year-olds: a rag to a bull for someone as passionately committed to child nutrition as Oliver, and he wastes little time in verbally goring the beleaguered PM. “Her maths don’t work. Remember it’s only three years [for each child], and we’re saying as Britain we can’t give them a free meal.“For me, the incredible humbling Theresa May’s just had, I’m fucking over the moon, because however you want to look at it…she was basically trying to stitch up the old and steal meals from the youngest and most vulnerable. And who the fuck puts foxhunting back in the manifesto? I mean, really.”

Oliver is also celebrating the most tangible triumph in his battle against childhood obesity: a new tax on sugary drinks, due to come into effect in 2018 in the U.K. As he puts it: “When you say to most British people, ‘Are you alright if we put six or seven pence on a can of [pop], and if it puts a potential billion quid into primary schools, we’ll use that to support sports and breakfast clubs in schools?’ people say, ‘Fair enough.’ ”

He describes himself as “apolitical”, but it is difficult to think of anyone outside Westminster who is more politically active. He has immersed himself more deeply in that murky world than any of his counterparts, but he is just too canny an operator to risk alienating the public by throwing his weight behind any one party. “In many ways, I sway more towards Jeremy [Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party] at the moment, but he wants to make all school [meals] free, and the problem I have with that is that when you make it all free, then it’s a race to the bottom again, because you just end up with accountants running the show.”

I first met Jamie Oliver in 1998 at the BBC Good Food Show in Birmingham. Nobody knew much about this amiable, slightly gawky 23-year-old, but the talk among a rather envious food mafia was that he was the Next Big Thing. Parading him around the show was producer Patricia Llewellyn, who had already had a hit with Two Fat Ladies, she had spotted Oliver while filming a documentary at London’s River Café, where he worked as a sous chef, and glimpsed his potential.

The Naked Chef’s portrayal of a carefree bloke with undeniable charm, a scooter, and a gift for slinging together great food for his mates became a national obsession.

When The Naked Chef launched on television the following year, it was an immediate hit. Its portrayal of a carefree bloke with undeniable charm, a scooter, and a gift for slinging together great food for his mates became a national obsession, and the old Anglo-Indian word pukka (slang for “genuine”) re-entered the language. Another two seasons followed, as well as three bestselling cookbooks. (Pukka, by the way, is no longer part of his vocabulary: “Even I found it annoying.”)

There was, inevitably, a backlash, particularly when Oliver signed a deal with Sainsbury’s to promote the supermarket in a series of TV ads: more than 100 in all, over 11 years, reportedly earned Oliver over £10-million ($16.6-million Canadian). Critics accused him of selling out, of sacrificing his principles for Sainsbury’s silver. Such accusations still dog him. His defence is that, for activists to actually achieve change, they have to work within the existing system. With Sainsbury’s, he tried to persuade consumers to buy and cook sustainable fish, and he got the supermarket to insist on higher welfare standards for its poultry.

A more recent collaboration—and another multimillion-pound deal, for a range of frozen ready-made meals—is with Sadia, the Brazilian poultry producer that raises an incredible 20 per cent of the world’s chickens. Oliver is unapologetic, despite an avalanche of criticism from all sides. “I increased awareness of RSPCA Freedom Food standards in Brazil, and we’ve done more positive things on a bigger scale than anything, or anyone, I know of has done in the last 50 years. In one year. I’ve done my fair share of paint-on-the-wall activism, and we still do documentaries and start petitions, but if you really want system change, you’ve got to work inside it. So I get activists now having a go at me. They’ll go, ‘You fucking sellout, why are you working with them?’ ” Oliver, say his critics, is an outsider who, for reasons of money or ego, has taken the easy route by colluding with the very governments and businesses he previously held to account.

The reason he has attracted so much criticism may be that he was the first major figure in the food world to speak his mind, and for some, he was an upstart who should never have left the stove. Many television cooks preceded him, but none showed much interest in politics. Not the Galloping Gourmet, not Nigella Lawson, not Keith Floyd—a personal hero of Oliver. “One of my regrets is never having met or worked with Floyd, even just to say, ‘We made gnocchi together and it was a nightmare’ ”—none of whom saw food in any wider social context than a dinner party.

Oliver has more in common with Alexis Soyer, the innovative, socially progressive French chef at the Reform Club in the 1830s, who marketed his own tabletop “magic” stoves, opened soup kitchens in Dublin during the Great Famine, and lent his image to sauces for Crosse & Blackwell before quitting the kitchen to embark on lengthy tours of the country, cooking in prisons and for the army, advising hospitals on their meal plans, and visiting asylums and workhouses. Shocked at the British ignorance of nutrition, he wrote several cookbooks, including Soyer’s Charitable Cookery and A Shilling Cookery for the People.

Still, Oliver has sold more books than Soyer. “You can look at the books,” he says, riffling through the pages of Jamie’s Comfort Food, “and you can take them apart in seconds and say, ‘Okay, that one he did because he needed to do it, and that one he enjoyed, that one I don’t think he enjoyed very much.’ Save With Jamie was [after] the recession kicked in, Comfort Food was at the end of the recession. They all have their place.”

His two Super Food books neatly capture the dichotomy between science and populism. “I’m doing a master’s degree in nutrition now, but I was still doing my first qualification then, and all the people who were teaching me hated the word superfood. And they were utterly right, but if your job’s to communicate with the public en masse, then you have to give it a hook.”

“If your job’s to communicate with the public en masse, then you have to give it a hook.”

His new book, 5 Ingredients: Quick & Easy Food (there is a TV series as well, airing on Gusto), will be published by HarperCollins in Canada this October and features more than 130 recipes, each with—you guessed it—just five ingredients. “I started writing it with four ingredients, but I felt that I was just giving recipes, I wasn’t giving me. I don’t want to be too romantic about it, but I think after 20 years the public does expect a bit of a twist and a surprise.

“What started out as a nice hook that I thought the public were screaming for ended up being something way fucking cooler. In cooking terms, it became a story about best friends.” Although aimed at time-poor home cooks, “I also think it’s legit for a really good chef as well, not because I’m a genius but because I think you’re never too good or too old to be reminded to take one ingredient out of a dish. The book’s secret ingredient is restraint.”

Restraint is something Oliver has had to learn, a concept that was alien to the younger, more gung-ho Jamie. His restaurant empire shows off that ambitious streak. Oliver’s most prevalent chain is Jamie’s Italian, of which there are 66 locations worldwide (Canada’s two outposts are in Toronto’s Yorkdale and Mississauga’s Square One shopping centres). Six closed in the U.K. since the Brexit vote, but there are plans to open another 22 globally. Other establishments include two locations of Barbecoa in London, which specialize in “traditional fire-based cooking”; Fifteen, his very first restaurant; and Jamie Oliver’s Diner in Piccadilly Circus and at Gatwick Airport.

Now 42, Oliver seems philosophical; his outrage at the iniquities of global nutrition is still there, but it simmers more gently, and he is modest enough to learn from people. And he’s able, as he puts it, “to shut my fucking gob” should the occasion demand it. He recently travelled to South Korea to investigate the factors underlying longevity—tending your own plot of land was one of them—“and the oldest person I met was 117. She gave me an hour of her time and then with brilliant style said, ‘Listen, I haven’t got any more time to talk to you, I’ve got to go and do some gardening.’ ” At the other end of the age range, he had a humbling experience in Puglia. “I’ve been making pasta for 20 years, and when I first went to Bari, a seven-year-old girl just smashed me to pieces.”

Which is not to say Oliver has lost the ability to annoy people. In the last year or so, his comments on breastfeeding, his inclusion of chorizo in a paella recipe, and even a photo of him cooking with one hand while cradling his infant son in the other have created storms across social media platforms. Has his skin become thicker over the years? He muses on this for a moment. “When you’re perceived as a do-gooder or whatever, it’s not easy. It’s a tough old business if you can’t sail, and it’s still pretty bumpy if you can.”

Grooming by Julia Bell.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter.